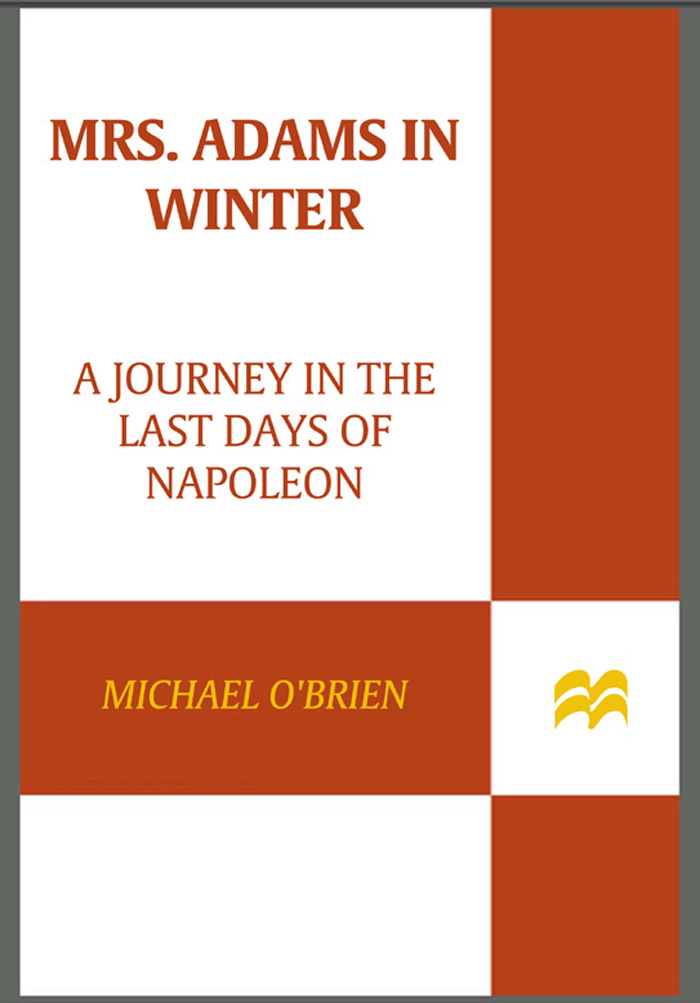

Mrs. Adams in Winter

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

18 West 18th Street, New York 10011

Copyright 2010 by Michael OBrien

All rights reserved

Distributed in Canada by D&M Publishers, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

First edition, 2010

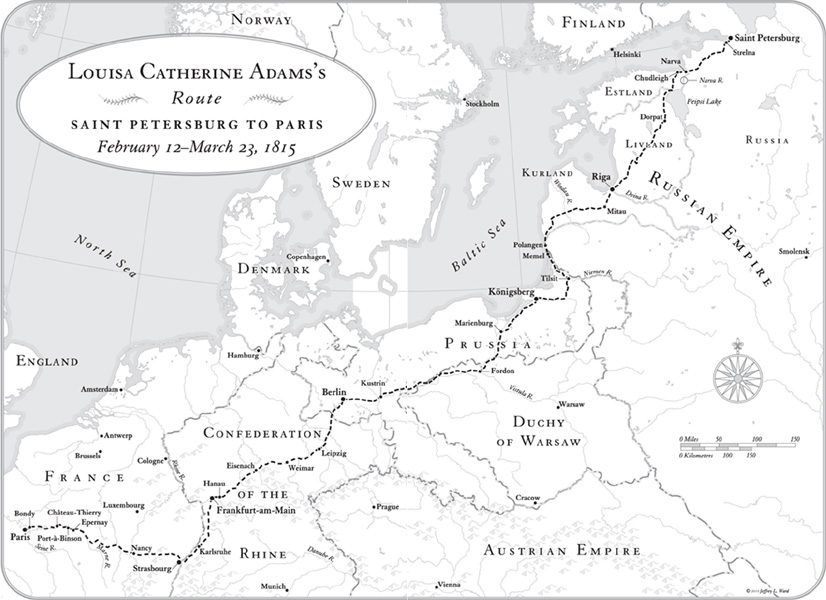

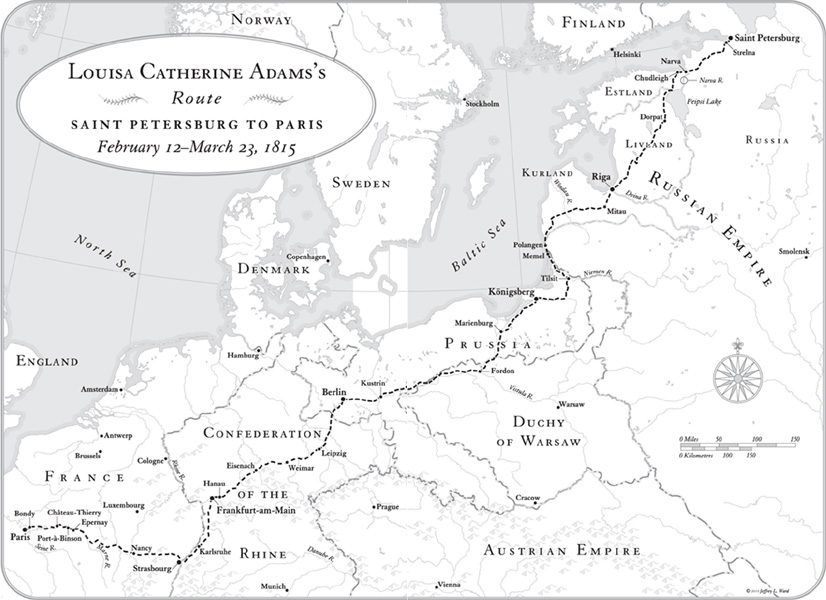

Map on pages xxi copyright 2010 by Jeffrey L. Ward

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

OBrien, Michael, [date]

Mrs. Adams in winter : a journey in the last days of Napoleon / Michael OBrien.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-374-21581-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. EuropeDescription and travel. 2. EuropeHistory17891815. 3. Adams, Louisa Catherine, 17751852TravelEurope. 4. Adams, John Quincy, 17671848Family. 5. Coaching (Transportation)EuropeHistory19th century. 6. RussiaDescription and travel. 7. Baltic StatesDescription and travel. 8. GermanyDescription and travel. 9. FranceDescription and travel. I. Title.

D919.027 2010

940.27092dc22

[B]

2009025437

Designed by Abby Kagan

www.fsgbooks.com

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Frontispiece: View of the Moika and Palace Bridge by Michel Franois Damame-Demartrais (1812), 2009, State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

For

Heather and Ross

and

in memory of Brian

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

A S MANY STORIES DO , this one started within the family. The tale was first told in a Paris hotel in the spring of 1815, when a very tired Louisa Catherine Adams was reunited with her husband, John Quincy Adams, and explained what had happened to her. Beginning in winter, for forty days she and her very young son had been traveling across Europe in a heavy Russian carriage from Saint Petersburg, through the Baltic states, across Germany, and into France. It had been a difficult journey. This was Napoleonic Europe and there had been danger, battlefields, and fear. At first, she herself was inclined to understate what she had done, but eventually she saw that there might be significance in her journey. She became shyly proud of the accomplishment, as did members of her family, who began to speak of it in conversation and eventually in print. By 1836, Louisa Adams thought enough of her 1815 experience to write a memoir of it. By then, she had lived in the White House as the wife of an American president and was known for belonging to a great political dynasty, the Adamses of Quincy, Massachusetts. Later, she was known not only as the wife of John Quincy Adams and the daughter-in-law of John Adams, but as the daughter-in-law of Abigail Adams, because Abigails fame as an American revolutionary and a woman began to spread, after her letters were first published in 1840. Later still, Louisa Catherine Adams would be known for being the grandmother of Henry Adams, the great historian and autobiographer, who would make her a significant character in his own story.

Living among the Adamses had a way of defining you. You were the wife of this Adams, the daughter-in-law of another Adams, the mother of yet another Adams. Apart from Abigail, they were mostly men, important men who helped to invent the United States, redefine its foreign policy, save the Union, and rewrite American and world history. They were men who not only deserved fame, but had been trained to earn it. But if you were a woman and an in-law, this was not an easy business, all this ambition and accomplishment. It came at a price. Louisa Catherine Adams, ne Johnson, paid this price with much reluctance and, in the various memoirs she wrote late in life, tried to reason out how it had happened, what life had done to her, and how she had passed from living as a child in London to the places her husband had taken her: an apartment over the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, an old homestead in Quincy, a dacha near Saint Petersburg, a mansion in Washingtonthese and many more places. Among these memories, her journey from Saint Petersburg to Paris acquired an iconic significance, as the moment when she had proved herself, not only as Louisa Catherine Adams, but as a woman acting in the name of other women.

She was right to think the journey could yield meanings, and this book attempts to reconstruct some of them. First, since this is a story about a woman traveling, it must be a biography of that woman, at least up to 1815. (Later is a different story, only a little told here.) A life can have meanings opaque to the person living it, but Mrs. Adams herself was most self-conscious about family, identity, and gender. For her, family meant two things: growing up a Johnson and becoming an Adams. She liked to remember the first as easy and the latter as hard, but she was notable for trying to hold on to being a Johnson, even when being swallowed up by the Adamses. The incompleteness of her transition from Johnson to Adams was partly explained by the richly complicated relationship that was her marriage, since John Quincy Adams was often difficult, sometimes kind, usually fascinating, and always stubborn. She never really knew whether her marriage had been a success, if she closely weighed the pain and the happiness, as she often did. As a wife, she was obliged to face many demands, for the partner of a diplomat and politician was a chess piece in several great games. As a First Lady, she had to endure what many such women had to endure: the sacrificing for a husbands early career and the splendid miseries attendant upon its later, always mixed success. But for Louisa Adams, being a mother was almost harder than being a wife, because she had a debilitating succession of miscarriages and one stillbirth, and, of the four children she bore, only one was to survive her. Because of this, she was only fragilely knitted into the succession of generations and never quite became a matriarch, which was what her culture said a woman should be.

In her mind, this sense of being an outsider was much tangled up with the worrisome business of identity. She had been born in England of a colonial American father and an English mother, had spent the impressionable years of her girlhood both in France and England, and then married an American who immediately took her to live in Prussia. She was twenty-six before she set foot on American soil and only eight years older when she left again, this time for six years in Russia and two back in London. She did not become a permanent resident of her husbands country until she was forty-two and, by then, had lived in Europe for thirty-four years. She remains the only First Lady to have been born outside the United States, a fact that John Quincy Adamss political opponents liked to mention as evidence of her disloyalty and probably his, too. If she were living now, it would be easy to find words to describe hermigrant, transnational, bicultural, bilingual, hybrid. Many a modern novel, history, and sociological treatise has sympathetic portraits of such women. But 1815 did not have the same words and sometimes had less sympathy. What it meant even to be an American was unclear then, though the Adams family was working at a clarification, and Louisa Adams spent the first half of her life among a cosmopolitan elite, which administered countries but did not always identify with them. Political and cultural nationalism was a new thing, more important to her husband and in-laws than to her. Yet she felt this cultural pressure acutely and was more than a little lost, because she never wanted to call herself En glish and, though she often proclaimed herself an American, she was less sure that others acknowledged her right to do so.