This is a serious history, yet an immensely readable oneinformative, gossipy, and grand fun.

New York Times Book Review

This beautiful book stimulates the mind as well as the eye

Chicago Sun-Times

An alluring invitation into the labyrinthine corridors of the Turkish harem.

San Francisco Chronicle

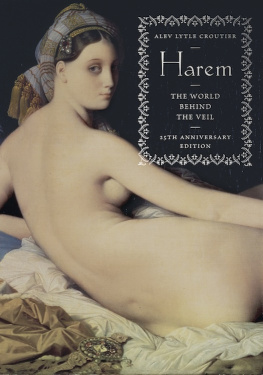

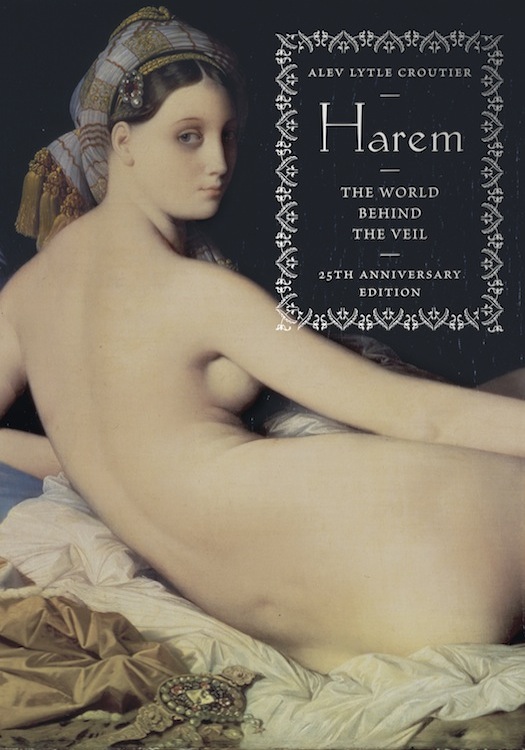

About Harem: The World Behind the Veil, 25th Anniversary Edition

In this fascinating illustrated historya worldwide best sellerAlev Lytle Croutier explores life in the worlds harems, from the Middle Ages to the early twentieth century, focusing on the fabled Seraglio of Topkapi Palace as a paradigm for them all. We enter the slave markets and the lavish boudoirs of the sultanas; we witness the daily routines of the odalisques, and of the eunuchs who guarded the harem.

Drawing on her own family history, Croutier also reveals the marital customs, child-rearing practices, and pastimes of middle-class harems, the womens quarters of ordinaryalbeit often polygamoushouseholds. Finally, she shows us how the Eastern idea of the harem invaded the European imaginationin the form of decoration, costume, and artand how Western ideas, in turn, finally eroded a system that had seemed eternal.

This revised and updated 25th Anniversary Edition of Harem includes a new introduction by the author, revisiting her subject in light of recent events in Turkey, and the world.

About the Author

Alev Lytle Croutier is the author of Taking the Waters (Abbeville) and three critically acclaimed novels, The Palace of Tears, Seven Houses, and Leyla: The Black Tulip. Born in Turkey, Croutier studied at Oberlin College and founded the publishing company Mercury House.

Harem is also available in paperback.

To view our complete selection of e-books, visit www.abbeville.com/digital.

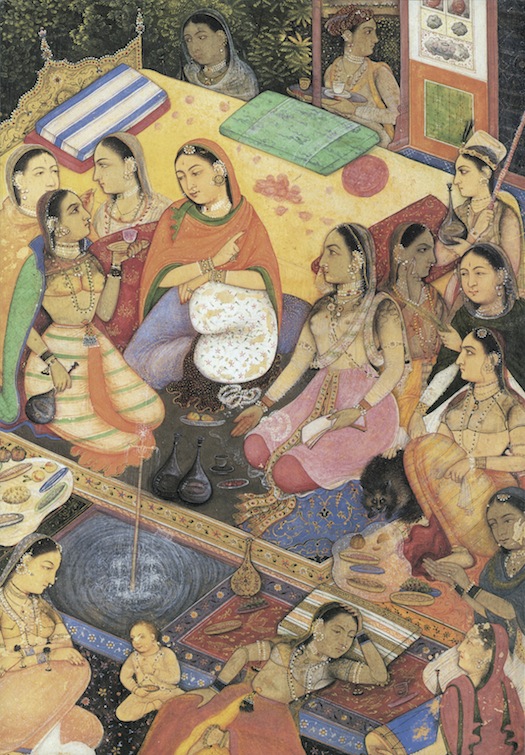

Detail of , by an unknown artist.

To all who danced the seven veils, my mother, grandmothers, and aunts.

Contents

meaning, origins, polygamy, slave markets, harem of the Seraglio, acquisition of slaves, training of odalisques, sultanas, eunuchs, dynasty, the Golden Cage, death, the world of extremes

harem walls, gardens, games, pools, riddles and stories, poetry, prayer, secrets of flowers and birds, opium, song and dance, shadow puppets, shopping, excursions, visits and outings, festivals and special days, disenchantment

passing of the veil

marriage of sultans, harem women and politics, valide procession, princess sultanas, remarriage of sultanas, accouchement and birth, death of sultanas, Roxalena (Hrrem Sultana), Ksem Sultana, Aime DeBucq de Rivery (Nakshedil Sultana)

Sleyman Aa, origins, types of eunuchs, eunuch trade, procedures, Chinese eunuchs, effects of castration, sexual desire and consummation, marriage of eunuchs, regeneration of genitals, the chief black eunuch (kizlar aasi)

the go-betweens, romance, gifts, henna night, weddings, husband-wife relationships, polygamy, relationships among wives, superstition and charms, upkeep, odalisques, jewelry, living quarters, bundle women, death

One Thousand and One Nights , wind from the East, Lady Mary Montagu, journey to the Orient, John Frederick Lewis, the Romantics, Jean-Lon Grme and the camera, Amadeo Count Preziosi, Empress Eugnie, Pierre Loti, emancipation of the East, the last picture

twentieth-century Orientalist threads, movies and television, harems today

Harem Revisited

Its odd to realize that a quarter-century has passed since the publication of Harem: The World Behind the Veil , and its still alive. I was delighted when Robert Abrams, my former publisher, had the idea of reissuing the book on its twenty-fifth anniversary.

Harem was the first book to explore this secret world of women from a feminine perspective. My intentions were primarily personal and cultural: to reflect on my family history and demystify the concept of the harem, which the Western imagination had turned into a dark, exotic, and erotic dream. I wanted to show the complex realities of this utterly private realm, which were far removed from the titillating depictions of odalisques by Western painters and writers. At the same time, I also considered what these fantasies said about the West itselfwhy it wanted to see its own women in a romantic Oriental guise.

Harem originally took me ten years to research and write, tracking down volumes in the dimly lit libraries and dusty archives of strange cities, digging into family stories, or having tea with ancient ladies who had lost their logic but still could make evocative connections in the interstices of their memory, memory that was as fragmented as the idea of the harem itself. No definitive sources existed on the subject. No Google to search. No Wikipedia to consult. It was simply a low-tech, labor-intensive process of assembling tesserae that had, like most Turkish antiquities, been scattered into faraway places.

Im very pleased that other writers and scholars have since built on my research and produced remarkable new insights into harem life. Their work has claimed an important space in womens studies and led to more understanding, more dialogue.

Since the first publication of Harem , the world has changed, and we have, in particular, seen many intense dramas concentrated on the Middle East: the Gulf War, 9/11, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the Arab Spring, the relentless conflict between Israel and Palestine, and a tsunami of Islamization. Partly as a result of these events, and partly because of increased Moslem immigration to the West, the Islamic gender issue has come under more scrutiny. On the one hand, Moslem women are obtaining much better education for themselves and their children, gaining greater visibility in civil society, and becoming more entrepreneurial. On the other hand, extreme Islamization threatens to create a new regime of legalized inequality.

I have watched Turkeymy birthplace, the worlds hope for a secular Moslem countrychange its face in just a couple of decades. First the number of women wearing hijabs increased by leaps and bounds, and then odd, ninjalike figureswomen in burkasappeared on the streets walking behind their husbands. The insinuation of Islamic couture began with a peculiar headpiece that came from the South, changing a womans silhouette: the turban , a scarf worn with a cap inside that looks like a bun. Then there was the burkini , a very modest type of swimwear in the form of a hooded pantsuit that covered the whole body except the face, the hands, and the feet.

At the street markets in Istanbul, a multitude of stands sell womens underwear, and it always astounds me to see a male merchant and women in hijab pass back and forth a sexy bra or bikini underwear. Rose, says one of them. The other opts for jasmine. The merchant reaches below the case and pulls out some thongs embroidered with flowers around the crotch. You pull the velcroed flap, similar to those in magazines advertising perfumes, and voila.

The word harem has even begun to reenter the common lexicon in Turkey. The current prime minister recently accused his opposition of invading his harem, that is, his private life, or his protected and sacrosanct spacean inexcusable act of heresy or haram . I realized that although the institution itself had been illegal for a century, the chapter on harems had not closed. The clash between civil and shariah law seemed insurmountable.

Next page