This book made available by the Internet Archive.

f,i,J^MM.M/A

Water is H.O Hydrogen two fmrts Oxygen one

But there Is also a third thing That makes it water. And nobody knows what that is. D. H. Lawrence

I am writing this book sitting in a well house, a tank containing an enormous amount of water above my head, constantly pumping. Sometimes I fantasize that a water spirit is overseeing me writing a book about itself. Other times I fear that the tank might burst from pressure and I could perish in a deluge.

Out of my window I see a panorama of a vast ocean, waves crashing, whales migrating, fishing boats docked around the reef, and in the distance, meticulously painted ocean liners crossing the horizon. I'm thinking of the book I'm writing about water. I'm thinking of the ways that water has touched me in my own life and continues to without my even knowing it.

Water is the most valuable element in our lives. It is a dancer of many forms. It makes sounds of many pitches, passionate, soothing, and ethereal. Water's hypnotic innocence hides nothing and yet it is still a mystery, full of endless associations, sacred and profane, creative and destructive.

Curiously, I was born under the sign of Aquariusthe Water Bearer in a house facing the sea, and in my life now I am living in a house facing another sea. Wherever I go, I look for sources of waterthe ocean, hot springs, or great baths. But I'm also terrified of water, having almost drowned twice and survived a major flood. The last San Francisco earthquake caught me, of all places, sitting in a bathtub full of water.

Everyone has their water stories and tales; without much provocation, they seem to pour out. Many of mine took place on the Aegean coast of Turkey when I was a child. I'd often see, out of my grandparents' window, a sad donkey pacing round and round, and the waterwheel turning. Or watch the nomads riding their camelsmagnificent animals with water storage cells in their stomachs that render them invaluable for desert crossing. Sometimes I'd catch a glimpse of my grandmother talking to the well or throwing coins into it when no one seemed to be watching. Sometimes I did the same.

We lived through endless seasons of drought when not a drop of water fell, and what the reservoirs contained was rationed out infrequendy. As

KTO\"\\\^VN\\\VB,WJ

.JB^W; !!i!M!i^ill^L^ili!!{!!IhiM!^L'l^al^||l!L^'!!'L'L^L^ll^!i!'X!!!.:.'L^!.;.!.!!!,..hi.'i.'iiili!!!;!.'.!!!'!! j ._.J....l!!!!

g!!!lS!!!!J^^^

Benjamin Franklin's Poor Richard's Almanac observes: "When the well's dry, we know the worth of water." Imagine turnmg on your faucet and nothing comes out but a mocking hiss. Imagine not being able to bathe, flush the toilet, or wash soiled diapers for days, sometimes weeks! But the drought motivated us to take clay jugs and buckets and draw water from a central fountain. Soon this became a special watering place where women gathered and enjoyed social encounters and shared gossip. Around the corner, men found their pleasure in teahouses, smoking waterpipes.

I recall many times when my father dragged us to a country spa where we endured sulfurous humidity and were forced to drink horrible-tasting waters: because they were supposed to make us healthier and live longer, it was all right to suffer.

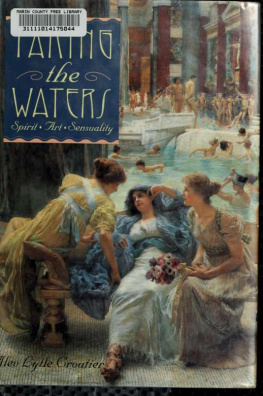

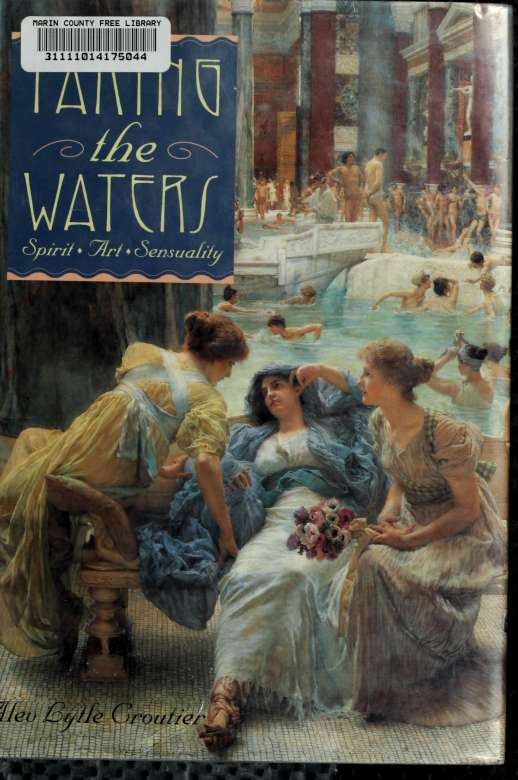

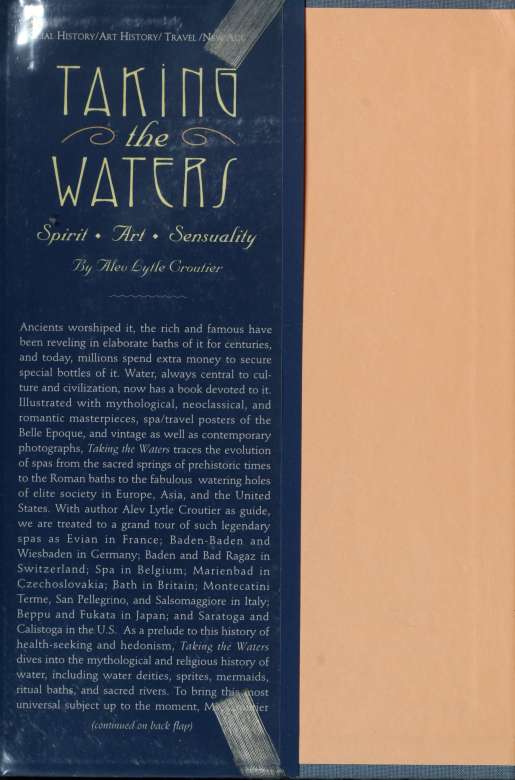

My fascination with the philosophy of bathing began in 1989, when Art dl Antiques magazine asked me to write an article on baths in art. I recalled that the house in which I was born had a haniani, or communal bathhouse. It was fun and mysterious. When, a few years later, my family moved into a modern apartment that boasted a shower and privacy, I missed those rituals. Fortunately, I returned to the world of hamams when I attended a girls' boarding school in Istanbul. Every Saturday morning, trailing bornozes and clacking fmttens, we slithered into a hamam with brilliant tile walls and marble sinks. Then a twelve-year-old, I was entering the most exclusive society of young voluptuaries, in which the older girls flaunted their bodies before us as a form of territorial gesture. Bathing, I discovered, was an artof silent abandon and sensuality.

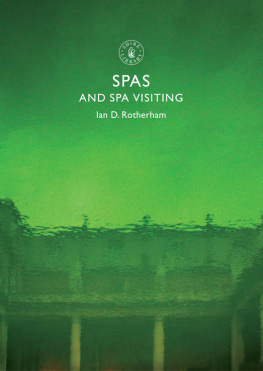

Moments of intimacy with water are endless. In my research I focused on the metaphysical, aesthetic, and rejuvenative aspects of the liquid element. I discovered how water has been a spiritual force m people's lives everywhereand still isand how wells, springs, and streams were worshiped because of their ability to heal. And how over the centuries these same sacred waters have evolved into popular baths and spas. I saw the manner in which this evolution mirrors and reflects the changing morals and attitudes of our society.

There are literally thousands of watering places in the world, ranging from secluded hot springs on the tops of mountains to the splendid spas of nineteenth-century European aristocracy. I made my selection among those that, rich in history, still manage to maintain the integrity of their waters and the spirit of the place. The spas I visited shared with me not only the mythology of their waters but also the world surrounding them, and became part of my personal mythology. Usually only a privileged few have access to these places, but through the generosity of many people I was also able to indulge in taking the waters and rejoice in how water has always influenced art, architecture, music, and cinema.

Water has its own language. I believe that by observing the ways that people have danced with it throughout history, we can gain a deeper awareness of this most precious element. A responsible appreciation of water is fundamental to our ecological, environmental, and spiritual values.

A.L.C.

i:3ISi5^gPOT;Kf:taiiahW*'tTa^3J:jeniiija:.?V4^na:Kt;t

. ,,,.,1 !,i , S.

-^'.-M '

R

BflSf^SK(^!!2WIi^Bl'lill!yi!iaiS;!li^T.^^^^^^