SPAS AND SPA VISITING

Ian D. Rotherham

Detail of image on .

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

Cheltenhams destiny was established in the early eighteenth century when local people noticed pigeons pecking at salt deposits near a spring south of the town. People began to drink the water in the belief that it would heal illnesses, and before long it was being sold to visitors.

CONTENTS

ANCIENT BEGINNINGS

Bathing is not absolutely forbidden to one who needs it. If you are ill, you need it; so it is not a sin. If a man is healthy, it cossets and relaxes the body and conduces to lust. (Barsanuphius, hermit from Palestine)

[Baths are] for the needs of the body not for the titillation of the mind and sensuous pleasure. (Pope Gregory the Great, AD 540604)

T HE EMERGENCE OF Georgian spas and spa towns has its origins in earlier uses of healing waters, baths and bathing, bathhouses and holy wells. From this mixed background there was a great expansion of spas and spa towns across Georgian Britain. To understand the remarkable rise of Georgian baths and spas, and the subsequent Victorian hydropathic movement, we must look back at social and religious attitudes to bathing, water and health in earlier times. The baths and spas became popular in the context, too, of the Georgian revolution in sumptuous living, of bagnios and bawdy-houses. Indeed, the boundaries between health resorts and places of assignation were often blurred. However, before the seventeenth century, licentious behaviour was much frowned upon and largely suppressed, and the bathhouses had suffered accordingly.

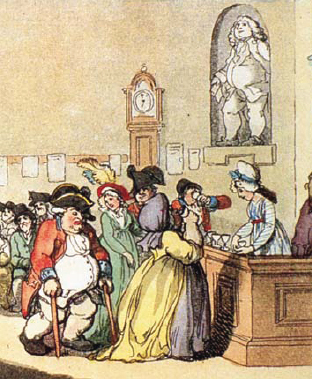

A medieval bathing scene used to depict the Biblical story of Bathsheba and King David.

Ptolemy, writing in Roman Egypt in the second century AD , described the Roman buildings at Bath as one of the wonders of the world a remarkable transformation from what, only shortly before this time, had been a boggy pool in a great marsh. The Romans established the town of Bath in AD 43, a spa bearing the Latin name Aquae Sulis (the Waters of Sulis). Archaeology has shown that the main spring of the Roman baths had been a religious shrine used by Celtic Iron Age Britons, and dedicated to their goddess Sulis. The Romans identified her with their own deity Minerva, and messages to her, scratched on to metal and known as curse tablets, have been found. These Latin messages curse those who had done wrong to the writer. One, written backwards so that only a god or goddess could read it, cursed the man who had gone off with the writers girlfriend or wife: Cursed be he who carried off Vilbia.

When the Romans left Britain, Bath fell into disrepair; the ruins were reclaimed by nature, and buried beneath mud, silt and peat. However, by around AD 6756, the town, now known as Ackmancaestor (Sick Mans Town), had a monastery and a small bathing facility. The ninth-century historian Nennius described it as:

[a] Hot Lake surrounded by a wall, made of brick and stone, and men may go there to bathe at any time, and every man can have the kind of bath he likes. If he wants, it will be a cold bath; and if he wants a hot bath, it will be hot.

For long periods, Christianity viewed baths, bathing, and especially bathhouses, very negatively. These were places of pleasure and sensuous delight, where good Christians might be tempted to enjoy the pleasures of the flesh. Bearing this in mind, the early Christian Church discouraged bathing. It was considered a pagan pastime or ritual, decadent and corrupting. The fourth-century ascetic Saint Jerome stated: He who has bathed in Christ has no need of a second bath. Baths and bathing were caught in a religious debate between Christian and pagan, and between western and eastern Christianity. Up to the Middle Ages, baths were strongly associated with serious threats to health, and to moral and sexual degradation allied to pagan and Islamic rituals. Writers were puzzled by Turkish culture, in which people bathed several times a week and washed even their genitals something considered outrageous to Christians.

The Roman Baths and Abbey in Bath in the 1970s. The citys long history and growth can be traced in the various phases of architectural development seen here.

The Roman under-floor heating system used here at Bath, and elsewhere, was based on the circulation of hot air through voids beneath the floor, which was supported by stacks of tiles.

Yet, despite disapproving of the great public baths, in centres such as Rome itself the western popes still maintained luxurious baths in their palaces for their own use. The Church, never slow in business matters, saw that bathhouses were potentially good moneymaking ventures, though old bathhouses associated with pagan rituals were exorcised before being put to good Christian use.

In early medieval times baths might be incorporated into church buildings or monasteries. These charity baths served both clerics and the needy poor, but over-indulgence, especially of hot baths, was still criticised as vain and harmful, while behind closed doors those in high office of both church and state still enjoyed them. For devout Christians, the problem with bathing was not so much the bath itself, but rather the clash between pleasant cleanliness and achieving spirituality by enduring physical and bodily deprivation. Since bathing was both pleasurable and functional, this troubled devout adherents. In short, the masses might bathe, but perish the thought that they might enjoy the experience.

The ascetic ideal of being unwashed meant that the idea of being dirty was spiritually good, the triumph of spirit over body. It stressed the particular importance of baptism as the only valid way of bathing in Christ. The followers of such ideals were mostly clerics, priests, monks and hermits. Seeking spiritual godliness through avoidance of personal hygiene was far from the modern concept of cleanliness being next to godliness, and these people would certainly have stunk.

By the eleventh century few bathhouses remained, though bathing continued for the privileged few. In northern countries such as Britain, bathing was limited to exceptional locations such as healing wells and springs. Yet a remarkable re-emergence was about to happen, which perhaps fulfilled all the worst expectations of the Christian ascetics.

BATHING AND BATHHOUSES IN MEDIEVAL TIMES

R ENEWED INTEREST in bathing coincided with increased public enjoyment of personal hygiene and the sensuous delights of bathhouses. However, the mixed roles of these establishments meant that by the fifteenth century the bathhouses, at least in cities such as London, had become synonymous with brothels. Remarkably, many were run by and for the Church as profitable business ventures. Upper-class private baths were already known as places of assignation, and the emerging public bathhouses soon had dual functions. Ordinary people, including respectable citizens with their children, would go to bathe, but prostitutes also operated from the same venues. A patron might go to bathe in hot water and steam, ordering food, wine, and perhaps compliant serving girls on the side. Thus the stews or stewhouses, as they were known, developed seamlessly from places of public bathing to houses of prostitution. As long as regular customers were not inconvenienced, then this was a legitimate business sideline.