TRUE CRIME FROM WHARNCLIFFE

Foul Deeds and Suspicious Deaths Series

Barking, Dagenham & Chadwell Heath

Barnet, Finchley and Hendon

Barnsley

Bath

Bedford

Birmingham

Black Country

Blackburn and Hyndburn

Bolton

Bradford

Brighton

Bristol

Cambridge

Carlisle

Chesterfield

Colchester

Cotswolds, The

Coventry

Croydon

Derby

Dublin

Durham

Ealing

Fens, In and Around

Folkstone and Dover

Grimsby

Guernsey

Guildford

Halifax

Hampstead, Holborn and St Pancras

Huddersfield

Hull

Jersey

Leeds

Leicester

Lewisham and Deptford

Liverpool

Londons East End

Londons West End

Manchester

Mansfield

More Foul Deeds Birmingham

More Foul Deeds Chesterfield

More Foul Deeds Wakefield

Newcastle

Newport

Norfolk

Northampton

Nottingham

Oxfordshire

Pontefract and Castleford

Portsmouth

Rotherham

Scunthorpe

Shrewsbury and Around Shropshire

Southampton

Southend-on-Sea

Staffordshire and The Potteries

Stratford and South Warwickshire

Tees

Uxbridge

Warwickshire

Wigan

York

OTHER TRUE CRIME BOOKS FROM WHARNCLIFFE

A-Z of London Murders, The

A-Z of Yorkshire Murders, The

Black Barnsley

Brighton Crime and Vice 1800-2000

Crafty Crooks and Conmen

Durham Executions

Essex Murders

Executions & Hangings in Newcastle and Morpeth

Great Hoaxers, Artful Fakers and Cheating Charlatans

Norfolk Mayhem and Murder

Norwich Murders

Plot to Kill Lloyd George

Romford Outrage

Strangeways Hanged

Unsolved Murders in Victorian & Edwardian London

Unsolved London Murders

Unsolved Norfolk Murders

Unsolved Yorkshire Murders

Warwickshires Murderous Women

Yorkshire Hangmen

Yorkshires Murderous Women

Please contact us via any of the methods below for more information or a catalogue

WHARNCLIFFE BOOKS

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Tel: 01226 734555 734222 Fax: 01226 734438

email: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

website: www.wharncliffebooks.co.uk

CHAPTER 1

He Died Like an Englishman 1900

B y 1900, the police force in Rotherham had become a more streamlined and professional group of men. Following the County and Borough Police Act of 1856, justices of the peace could now appoint rural police constables who would live and work in their own parish. Knowing the locality would ensure that such constables would know its inhabitants very well. The relationship between the population of these townships and their resident police constable worked generally quite well, although sometimes tensions would flare when police business had to be conducted. In July 1900, a constable doing his duty and delivering a summons taken out by another member of a family resulted in murder. Resentment had built up against the constable leading to his death and shocking both the community and his fellow colleagues.

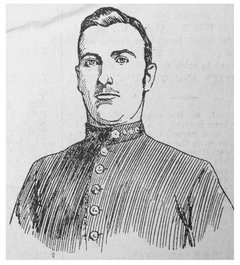

On Saturday 14 July 1900, the population of the town of Rotherham read about a murder which had occurred in a little hamlet just outside Swinton called Piccadilly. The murder of a police constable always excites a community and this one was no exception. On Tuesday 10 July, PC John William Kew, a 29-year-old constable, heard a commotion coming from the back lane of a neighbouring house and, always the professional, went to see if he could help. He left at home his wife and four children. Kew was a constable with the West Riding Police Force stationed in Rotherham and had lived at the hamlet for the past five years. He was well thought of, respected in the neighbourhood and people would often turn to him to solve their problems rather than face the formal police station in the town centre. He had been born at Boston in Lincolnshire and for a short time had served with the Lincolnshire Constabulary, earning much credit for his ability and in the way he carried out his duties.

PC Kew. Rotherham Local Studies & Archives

When Kew arrived at the scene of the argument at the back of a row of houses he found Charles Benjamin Backhouse, aged 23, with his wife and his younger brother Frederick Lawder Backhouse, aged 19. The family was known to be dysfunctional and a few weeks earlier Charless wife had taken out a summons against her young brother-in-law, for assault. Frederick had not been in court and in his absence he had been fined 40s (2) and costs. Henry Thompson, a neighbour to the Backhouse family, had warned Constable Kew that the two brothers had in their possession a revolver. This fact was probably uppermost in his mind when he arrived in the lane and saw the two brothers were arguing. He remonstrated with them both for causing a commotion and he told them that he was going to search them. At this point Charles stepped back, pulled out the gun and shot PC Kew, the bullet lodging in the upper part of his stomach. Despite his injury, this gallant police officer attempted to take the gun from Charles who casually handed the weapon to his younger brother Frederick who shot Kew once more, this time above his right hip. Unbelievably and despite his injuries, Kew managed to take Charles into custody and the two of them went back to the constables house. When the constables wife saw his injuries she called for a doctor who quickly arrived. Dr Fullerton sent for help to the local police station at Swinton and he made the injured man as comfortable as possible. Police Sergeant Danby arrived and handcuffed Charles, asking Kew in his presence what had happened. Kew indicated to say that Charlie had shot him and not to let him go. Charles, confronted by the two policemen, denied shooting Kew. When the sergeant left the house he saw Frederick outside the building, looking in through the window. Danby approached him and, after searching his person, found the gun in his trouser pocket. He arrested him and took him into the police house where once again in front of both brothers he asked Kew Who shot you? Kew replied once again that Charles had shot him first, followed by Frederick. Charles said nothing whilst Frederick admitted that he shot Kew.

At this point there was no obvious reason for the shooting; witnesses stated that previously there had been no ill will shown to the policeman from the two brothers. But it later appeared that it had been Kew who had delivered the summons to Frederick from Charless wife, but at the time neither man gave this as a reason. Kews condition worsened and Dr Fullerton summoned the ambulance of the nearby Warren Vale Colliery. The stricken man was taken into Rotherham Hospital where he died at 2.00am, two hours after being shot. Both the arrested men were taken into custody and the next day they were visited by Charless wife and their mother. It was reported that both women were very emotional and distressed. When the men were brought into court earlier that day the reporter noted that the men did not appear to understand the gravity of the charges made against them. The magistrates remanded the brothers for seven days to allow further investigation into the matter.

It seems that on the day of the murder they had been drinking in a public house in Rotherham called the High House. There they met a neighbour from Piccadilly named Inkerman William Gibbons who was a bricklayer at Thrybergh Hall Colliery. Gibbons knew the brothers quite well and he told the court that they had entered the pub together about 9.3010.00pm and left at closing time. He described the brothers as being a bit fresh, a euphemism for being drunk, and the three men walked back to Swinton together. On the journey Charles pulled out the revolver and showed it to Gibbons. He told him that it was a six-chambered weapon and it was primed and ready to use. His brother cautioned him, saying not tonight Charlie, in the morning. Charles then put his fingers to his forehead and mimicked shooting himself in the head. Gibbons thought that Charles was contemplating suicide, but put it down to both brothers being intoxicated. Charles then stated that no man or women would alter what he had in mind and when Gibbons asked him what was that he grandiosely said death or glory and touched the pocket in which rested the gun. There strangely also followed a conversation about where they were going to sleep that night. Gibbons was in lodgings with a family called Wheeler, but Frederick said that he was going to sleep out in the fields as he had done on previous occasions. Also, on the journey home, Charles stated mysteriously that they would not harm the mother or the children. When Gibbons was asked about this in court he was asked to repeat this statement as it was crucial to the prosecutions case, indicating that the murder had been premeditated. The three men arrived in Swinton and went into the Wheeler household where Charles wife, Annie Sanderson, along with Harriet Wheeler and her husband John were present. An argument ensued and Charles threatened Harriet saying, My God I will do for thee. He was waving the gun around and Gibbons told him to put the gun away before it went off and killed somebody. The two brothers went outside with John Wheeler, followed by Mrs Wheeler and Annie Sanderson. The argument continued but when asked what it was about the brothers would not say, only stating that it was family business. They were all congregated in the back lane, arguing, and this was where they were found by Kew. Gibbons said that only five minutes later he heard the first shot being fired.