CONTENTS

The Case of Ann Barber, 1821

The Death of Baby William, 1838

A Case of Domestic Violence, 1838

The Mystery of Christopher Winders Death, 1841

The Curious Poisoning of Sarah Scholes, 1842

The Execution of Thomas Malkin, 1849

The Case of Charles Normington, 1859

The Trial of John Kenworthy, 1860

The Acquital of John Dearden, 1872

The Execution of John Darcy, 1879

The Death of Margaret Laidler, 1883

The Case of Samuel Harrison, 1890

As always, writing a book is a team effort and my grateful thanks go to The History Press and, in particular, Beth Amphlett, who has been encouraging throughout. My grateful thanks go to Leeds Local and Family History Library, where the staff could not have been more helpful and obliging.

I cannot miss the opportunity of mentioning the particular help I received from Eric Ambler of Leeds Town Hall, who gave me a personal guided tour of the courts and the cells where the Leeds Assizes were once held. Knowing that hundreds, if not thousands, of prisoners had stayed there over the years, I asked him if there were ghosts still there and he told of a spooky occasion when he was with a colleague and the heavy, metal doors clanged shut behind them. There was no one near them at the time; the doors are extremely heavy and there is certainly no wind down there. Thank you Eric for that little story!

During the tour, I was able to see the cells beneath the Town Hall, which were very basic, and there certainly would not have been any luxuries for the prisoners not even bedding. I would also like to thank Mike Roddy, who works at the Town Hall and shared his love of architecture in the city of Leeds, which is a fascinating place to live and work.

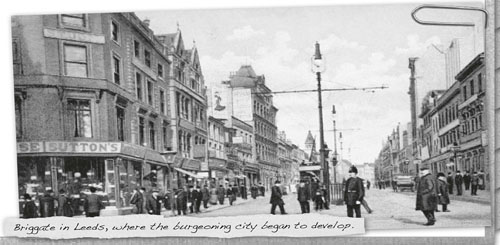

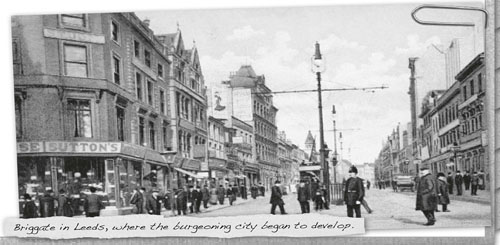

Leeds is an ancient place, which was first mentioned in the Domesday Book. Once the cloth market opened in Briggate in 1684, the burgeoning city began to develop. By the Victorian era, Leeds was a very prosperous place to live. The Industrial Revolution brought an influx of people into the town to work in the factories and workshops and, as a result of this, local businessmen wanted to show off their wealth and affluence, and the city saw massive redevelopment. New buildings such as schools, mechanics institutes and chapels sprang up around the town, paid for by generous benefactors. Leeds officially became a city in 1893, but at the other extreme of all this wealth was severe poverty. Poor housing and overcrowding were common issues in cities around the country at this time, and Leeds was no exception. Such unsanitary conditions led to an outbreak of cholera in 1849, which killed more than 2,000 people. As in every town and city of this period, there was a criminal underbelly that ran against the grain of those working hard to survive, and drunkenness and domestic violence were rife in the city. It is from this time that the cases explored in this book originate.

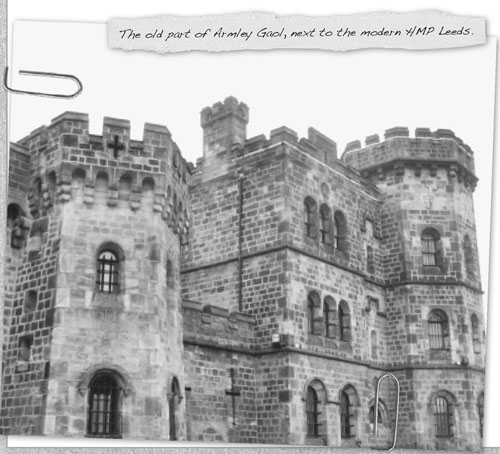

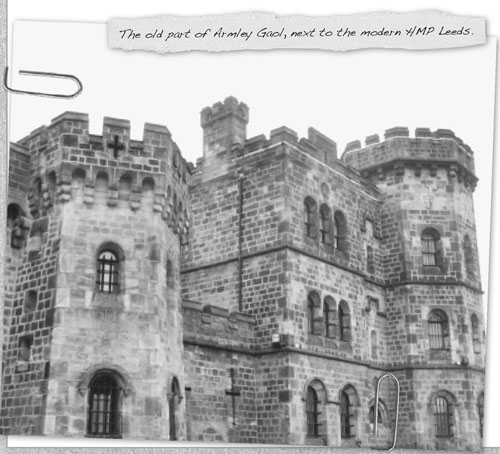

Historically, crimes of murder would have first been established at a coroners court, where the responsibility of the jury was not to prove the guilt of a man or woman but to identify the corpse and establish the cause of death. Many of these felons were then tried at the magistrates court, from where they would be sent to take their trial at the quarterly Assizes at York. The Assizes for the Yorkshire area were held at York Castle until 6 August 1864, when because of the proliferation of crimes in West Yorkshire they were then held at the Leeds Town Hall. Prisoners who were sentenced to death were usually kept and hanged at Armley Gaol, which was described as a grim, foreboding place, opened in 1847. The gaol is still open as HMP Leeds, which sits next to the modern prison of today. Thankfully, unlike York, there was only one public hanging in front of a crowd of people, before executions were then undertaken inside the gaol. As standard practice, the body would be hung for an hour before being cut down and buried in an unmarked grave within the precincts of the gaol. This was the fate of many of the people who murdered others in Leeds.

The following cases are from the period 1800 to 1900. They are varied and some so complex that even the criminal themselves were incapable of saying why they committed such atrocious acts. Most were committed for gain, whilst others took place through jealousy or after an excess of alcohol. Many of these cases have never been written about before, but all of them happened in and around the city of Leeds all those years ago. Thankfully, little remains of the squalor and overcrowded houses of the past. Beautiful parks abound and today, when I visit Leeds, I find it to be a bustling and rapidly expanding city. What I love most about it is the mix of brand new apartments and commercial buildings alongside older relics of great architectural beauty.

Margaret Drinkall, 2012

Case One

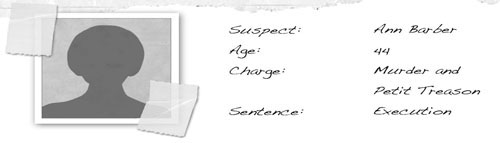

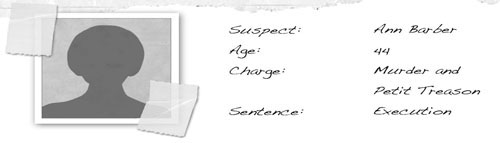

The Case of Ann Barber, 1821

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, a woman could be charged with the crime of petit treason the murder of her husband. In law, a mans life was seen as much more valuable than a womans, and up to the 1790s women convicted of such a crime could be burned at the stake. The murderess in this case was described in one local newspaper as being a wretched victim of impure desires. It is probable that she was convicted as much for her morals as the act of murder itself. So keen were they to convict her, in fact, that she stood charged with the crimes of both murder and petit treason.

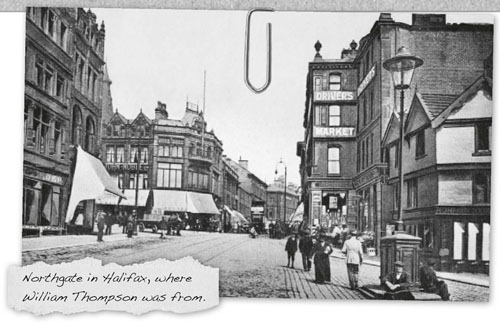

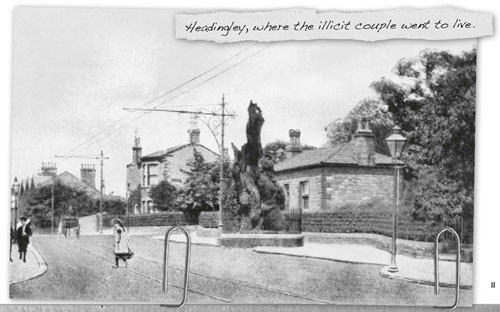

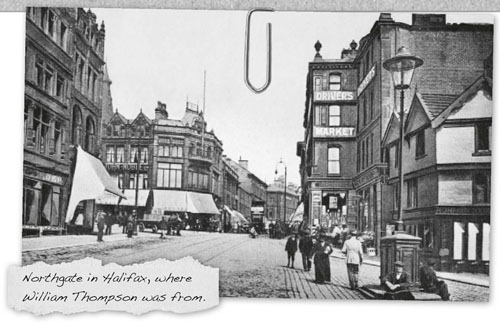

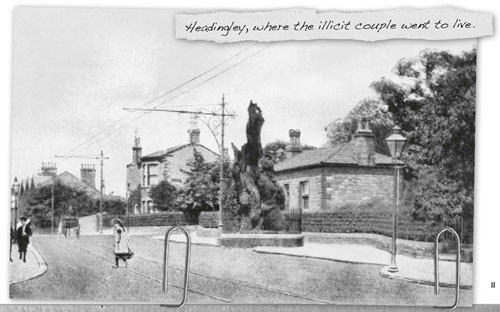

Ann Barber was a woman with a past. In 1821, she was forty-four years of age and married to James Barber. She had a child from a previous marriage and two daughters with James Barber, named Hannah, aged 15, and Jane, aged 9. It seems that at this time Ann Barber was cheating on her fifty-year-old second husband with a lodger a young man from Halifax called William Thompson. At one point, Ann and her lover decided that they were going to elope and they went to live together at Headingley on 21 December. Neighbours reported seeing them leaving the marital home at 6 a.m. with some furniture piled onto a cart. At Headingley, they rented a small cottage, which consisted of one room. They told the landlord, John Holmes, that they were man and wife, but he found out the truth and he threw them out. The couple returned back to Rothwell and, incredibly, her husband allowed the pair of them back into the house. However, the neighbours were not so forgiving and they strongly disapproved of this immoral behaviour. They castigated the couple and James Barber too, calling him a cuckold. Indeed, so much distaste was shown to Thompson that he moved out of the house in February 1821.