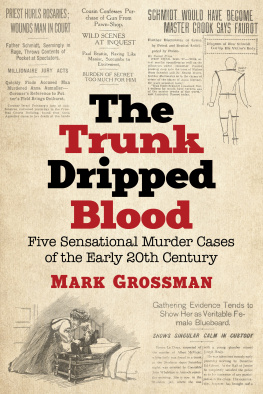

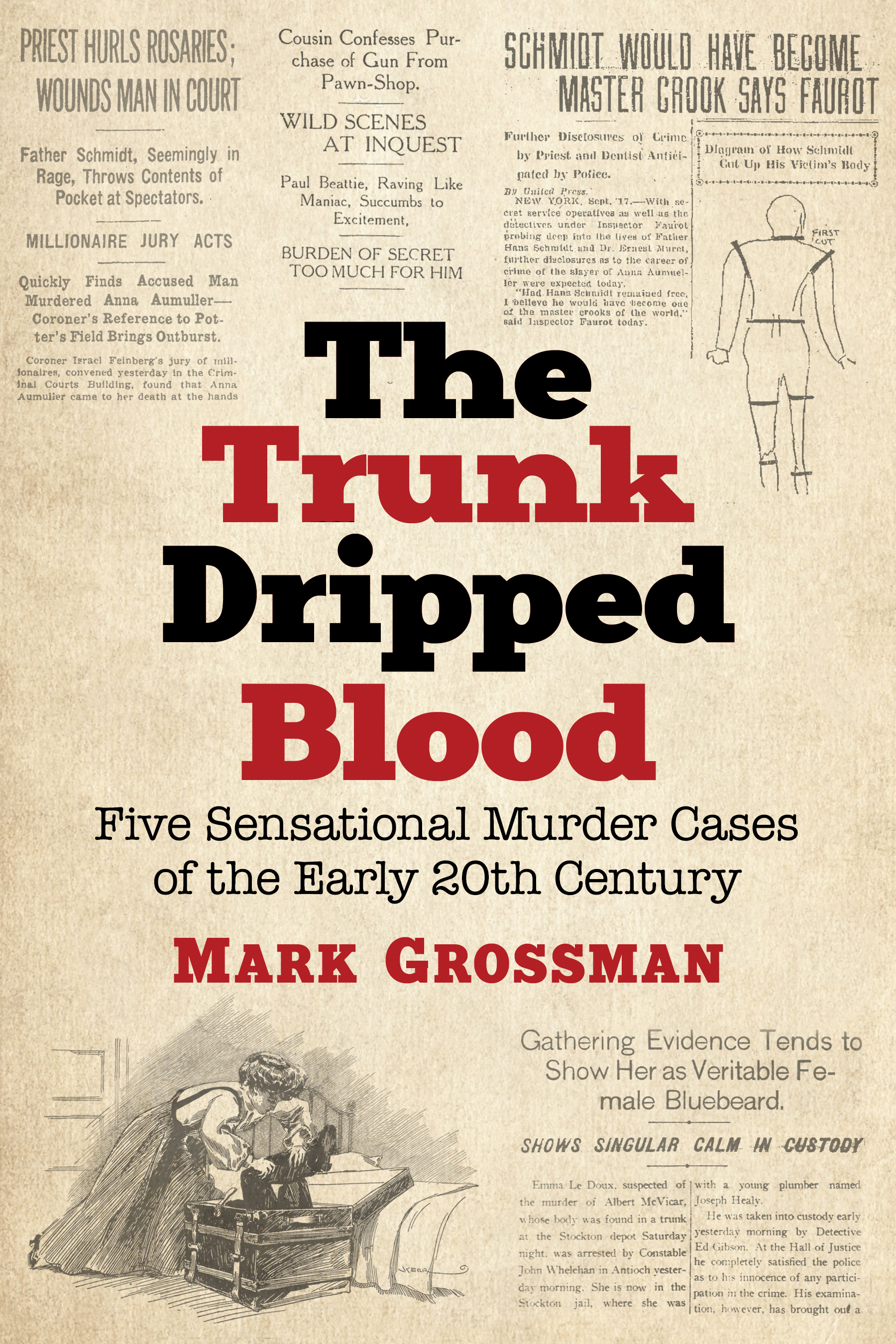

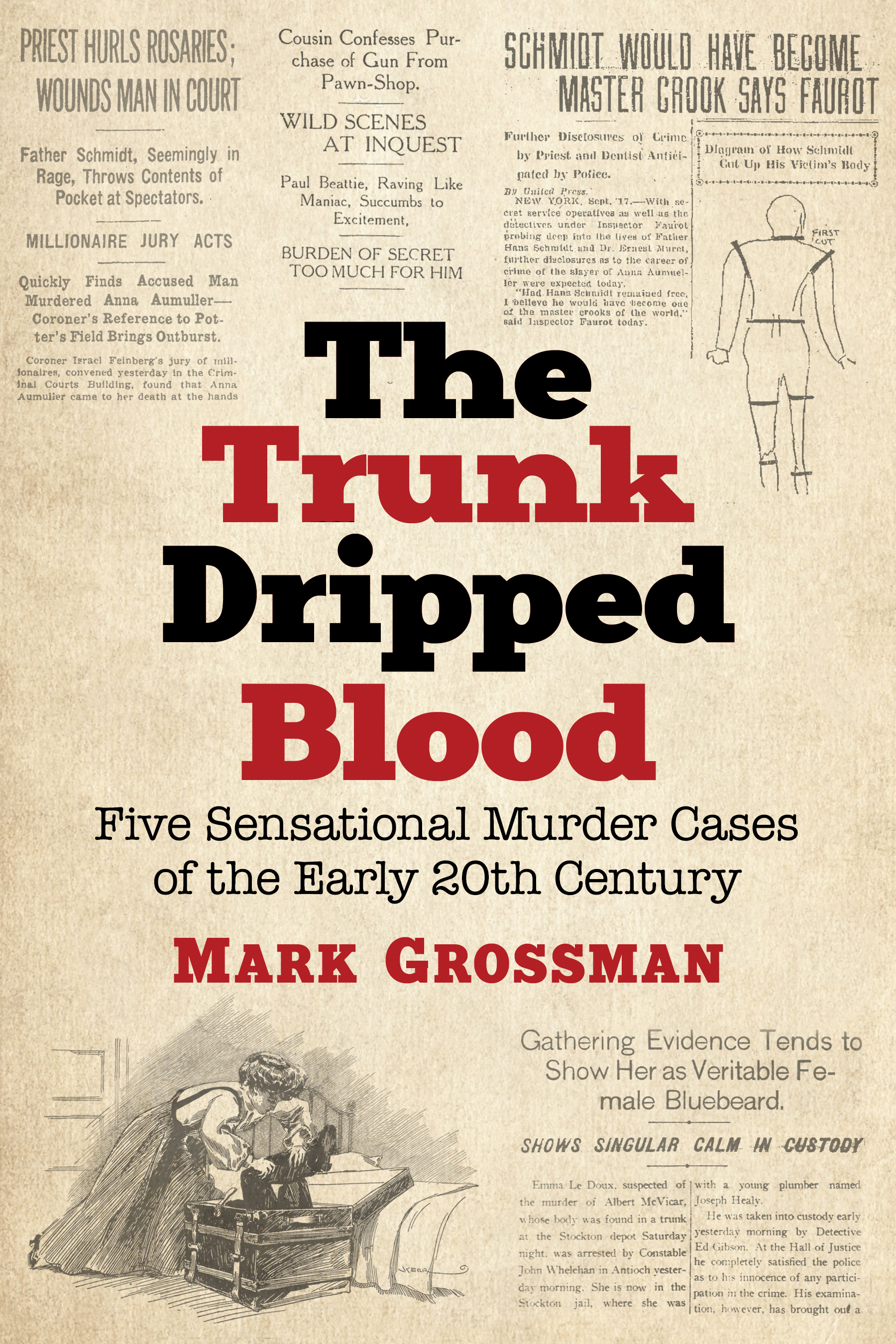

The Trunk Dripped Blood

Five Sensational Murder Cases of the Early 20th Century

MARK GROSSMAN

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-3013-7

2018 Mark Grossman. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Front cover: early 20th century newspapers articles

Exposit is an imprint of McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.expositbooks.com

Preface

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there were 15,809 homicides in the United States in 2014approximately 43.3 murders per day.

Such figures were not kept around the turn of the 20th century (the FBI didnt begin Uniform Crime Reporting until 1929) so we can only guess at the statistics of the day. And it is obvious from public records that murders generally were not publicized to the degree that they are today. Additionally, policing techniques were not the samethere were no forensics, limited use (at best) of fingerprinting, and no databases of suspects or convicts. Police mostly relied on shoe leather investigations to collect whatever evidence they could.

Yet, as always, true stories of murderthe evidence, the capture, trial and punishment of the guiltythrilled the public, despite (or because of) the horrific nature of the crimes. Newspapers played up sensational crimes with lurid headlines and images, in the decades before radio or television. Readers were fascinated by every detail, following the investigations and courtroom drama surrounding the OJ Simpsons and Scott Petersons of the day. Reporters made household names of the judges and lawyers involved in their prosecution and defense.

Those cases that have faded into history for one reason or another deserve to be explored. The following chapters document stories that few true crime writers or historians, or even aficionados of the genre, have come across except in passing. At the time, these crimes captured the nations attentionnow they reside in musty old newspapers and books. Their being forgotten does not make them any less important, or any less interesting.

The five crime stories herein are covered in detail from start to finishperhaps more completely than in the newspapers of the dayfully documented, with footnotes for each source. Years of research were conducted in many places; thousands of hours spent in newspaper archives in Washington, D.C., New York, London and Arizona, are represented here.

Where reports and transcripts contain words of a racially insensitive character, I have left them in the context of the times.

I hope the stories fascinate the reader as much as the research captivated me. Any errors, of fact or otherwise, are the responsibility of the author alone.

1

The cheapest crime I have ever heard of

The Midlothian Turnpike runs from Richmond, the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, west to the city of Midlothian, and then further west to Holly Hills. Now known as U.S. Highway 60, in 1911 the road was a major thoroughfare to and from the city.

On the night of 18 July 1911, dry goods salesman Henry Clay Beattie, Jr., and his wife of less than one year, Louise Wellford Owen Beattie were traveling on the turnpike on their way home from a pleasant night out in Richmond, whenaccording to what Beattie later told policehe noticed a man walking in the middle of the road.

Described as tall, with a brown scraggly beard, the man suddenly veered into the path of the car. Henry Beattie applied the brakes, at which point the man yelled, You had better run over me! Beattie said he replied, You have got all the road! and tried to pass the stranger.

Suddenly, without warning or provocation, the man raised a shotgun and fired a single shot at the car, striking Louise Beattie in the face and blowing off the top of her head.

Beattie stopped the car, jumping out to find himself in a deadly fight with the stranger. The man got the better of him, striking him in his face with the butt of the gun. Henry continued to fight, and, after a few moments, gained control of the weapon, despite the other mans apparent size and weight advantage. As he raised the gun and turned to shoot at the stranger, the man disappeared into the dark.

Beattie told police that he then threw the shotgun into the tonneau or back passenger seat of his car and climbed in, only then noticing that his wife had been shot in the head. Holding her with one hand while driving with the other, he sped five miles to the home of his wifes uncle, Thomas Owen, where he alerted the police.

The horrific murder of Louise Beattie (ne Belote) shocked rural Virginia. The Salem Times-Register called it one of the most horrible and atrocious murders known in the history of the State, and the story of a young mother senselessly killed on a lonely country road by a stranger who disappeared into the wilderness gathered steam in newspapers across the country.

Incredibly, this would be the first of two tragic murders in the Belote family. Just months after Louises death, Ida Belote would be murdered by Virginia Christian, her maid, who was convicted and put to death in Virginias electric chair.

The morning after the Beattie crime, the gun was found by the roadside by Mandy Alexander, identified simply as a colored woman. Bloodhounds from the Virginia State Farm were brought to the scene, but investigators ran into problems almost from the start. It was reported that [t]wo pools of blood, some distance apart, mystified the detectives who went to the scene at daybreak county and State officials of the law, and innumerable citizens were scouring the county in search of the murderer. An unnamed black man, initially arrested as a suspect, was released after questioning showed him to be innocent.

Two days into the investigation, the woods surrounding the turnpike for more than five miles [had] been thoroughly searched without revealing the slightest clue.

A coroners inquest to be held on the morning of 19 July was postponed. Reporters were told the reason for the delay was the lack of a qualified stenographer, but they soon discovered that detective Luther L. Scherer, a special agent for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway, and Detective-Sergeant Thomas J. Wren of the Richmond Police Department, two of the leading investigators, had asked for the postponement so that certain circumstances of the case would not be made public. The Times-Dispatch of Richmond reported: That the gun will tell the story is the unanimous opinion of detectives and special officers, but the gun appeared to be the only solid evidence uncovered by authorities.

Next page