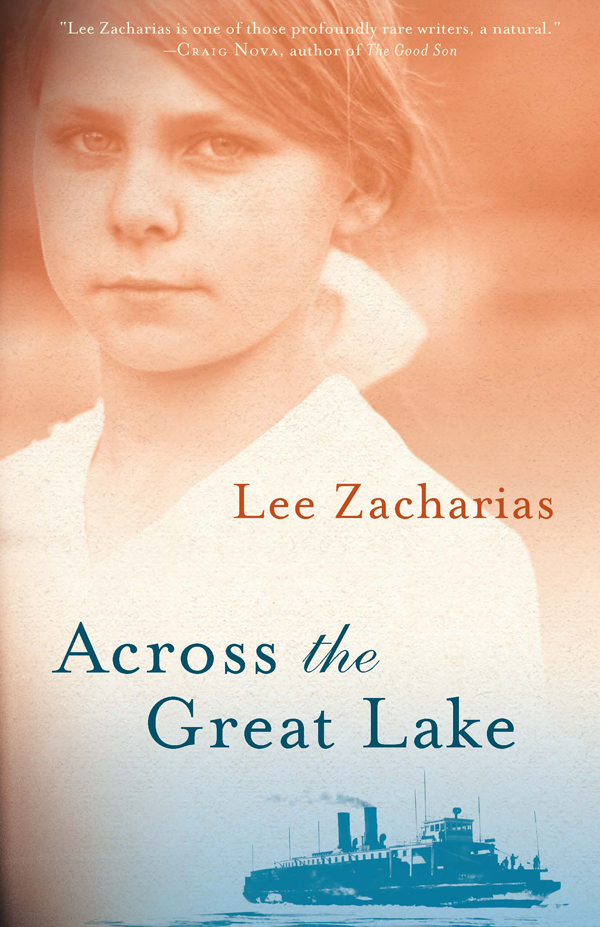

Also by Lee Zacharias

Short Stories

Helping Muriel Make It Through the Night

Novels

Lessons

At Random

Essays

The Only Sounds We Make

The University of Wisconsin Press

1930 Monroe Street, 3rd Floor

Madison, Wisconsin 53711-2059

uwpress.wisc.edu

3 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden

London WCE 8LU, United Kingdom

eurospanbookstore.com

Copyright 2018 by Lee Zacharias

All rights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations embedded in critical articles and reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any format or by any meansdigital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwiseor conveyed via the Internet or a website without written permission of the University of Wisconsin Press. Rights inquiries should be directed to .

Printed in the United States of America

This book may be available in a digital edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Zacharias, Lee, author.

Title: Across the great lake / Lee Zacharias.

Description: Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2018011386 | ISBN 9780299320904 (cloth: alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Michigan, LakeFiction. | LCGFT: Novels. | Fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3576.A18 A64 2018 | DDC 813/.54dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018011386

ISBN-13: 978-0-299-32098-0 (electronic)

For

Michael

and for our sons,

Max and Al

In memory of my father,

Joseph Ryan Ives

who served as a merchant marine from 1937 to 1945 but never spoke of his time on the oceans or the Great Lakes to me

For in their interflowing aggregate, those grand fresh-water seas of ours,Erie, and Ontario, and Huron, and Superior, and Michigan,possess an ocean-like expansiveness... They contain round archipelagoes of romantic isles... they have heard the fleet thunderings of naval victories... they are swept by Borean and dismasting blasts as direful as any that lash the salted wave; they know what shipwrecks are, for out of sight of land, however inland, they have drowned full many a midnight ship with all its shrieking crew.

Herman Melville, Moby Dick

To Lake Michiganthe only one of the Great Lakes without an international boundarysailing masters pay the utmost respect, not only because of this Lakes long history of sudden disaster, but because of the prevailing winds that can sweep its length to roll up backbreaking seas, the scarcity of natural harbors or even man-made places of refuge, and the crowning fact that it is the trickiest of the Lakes to keep a course on, due to currents caused by a flow around the Straits of Mackinac when the wind shifts.

William Ratigan, Great Lakes Shipwrecks and Survivals

1

We went to the ice. That was the year my mother died, but I do not remember her. What I remember is the ice, everywhere I looked, a world made of ice, and then the fire. But first there were the voices.

Get up, he said.

I cant, she said.

You mean you wont.

I cant.

Was I listening outside the closed door? Surely my mother taught me better, had told me that eavesdropping was not something a polite little girl would do. Such a strange word, eavesdropping. Did I know it then? Was I already a bad girl? Perhaps she despaired of me, I dont know. We got stuck in the ice, there was a storm, and while we were gone my mother died. My father was not a man of words, and now that so many years have passed, there is no one left to ask whether I was ever a good girl, a girl who might have deserved love, or not.

Theres other women lost a child.

You dont know.

I know enough.

A clot of silence seemed to thicken, though perhaps they only lowered their voices, perhaps I simply couldnt hear them.

For the last time, get up, he said. Youve another child needs tending.

Did she answer? My father was a captain. When he spoke people listened. They did what he said. Perhaps she repeated I cant, the only memory I really have of her, those two words in her voice. Or perhaps, when my father offered me as a reason for her to get back up and live, she said nothing at all. I had just turned five years old. In the hallway there was a yellow light in a sconce. It was a grand house, set against the hill on Leelanau Avenue, but the light had scorched a spot on the wallpaper, and there was a water stain near a seam, a small, brownish lake in the green-and-gray print. I used to spend hours perusing those blotches, as if imperfection was what my eyes sought from the start, though I dont remember whether I noticed them that night.

All right then, my father said. Im taking the girl.

Surely neighbor women would have cared for me, as they did later, after my mother died. I suppose its possible he never meant to take me, only to frighten her back into life. A railroad car ferry, those women would tell me later, their voices hushed because he was a captain and in our town a captain was beyond reproach, is no place for a girl, and in the dead of winter too. But my mother must have sunk back into her pillow and said nothing, because I went to my room, and not long after, he came in and dressed me in heavy woolens, pulled a cap down over my ears, and wrapped a scratchy scarf around my face. It was dark when we left the big house on our side of the harbor, the pretty side. He had an automobile, and we drove the snow-crusted road through the welcome gate with its model ferry on the crossbar around to the other side, where the boats docked and the men who worked on them lived behind their sagging porches in shabby little houses sided with tarpaper brick.

I had never seen the loading before. There was a great clanking as the railcars, those big freight cars, loomed up out of the darkness and rolled onto the vast lower deck of the ship, the flagship of the Annies, as the townspeople called the Ann Arbor Railroad ferries, though my father always called his ship a boat, as if it were no bigger than a dory. Later, inthe summertime, I would sometimes sit on the Elberta bluff with my stepmother, watching his ship pass between the stub piers into the big basin enclosed by the breakwaters and beyond, because a captain is never home and for the people who belonged to the captains and crews, such rituals are what passed for family life. Even from that distance anyone could see that it was not a boat such as you might take out to fish, but a huge and powerful ship with a tall, handsome pilothouse and big smoking stacks, no place for a girl, though I loved it, I cannot tell you how much I loved it. I came to know it inside out. I knew more than my father knew. Because it was not his job to watch me. He had a ship to command. No one on such a ship was in the habit of minding little girls, and no one on a ship in trouble could have spared the time. Today you would say I slipped below the radar, but there was no radar then, only a magnetic compass, lead and log lines. They forgot me, all of them except Alv, and I loved being a forgotten girl, a secret girl, a girl whose life began to speak to me down on the car deck and below, in the bowel of the ship where I was not supposed to be, a girl who believed her real life was beginning.

As the cars loaded I listened to the buzz of the mens voices and burrs of their laughter, barely audible beneath the loud wheels, metal on metal, the boom of the sidejacks and stanchions and ringing of the chains, then the groaning of the ropes and hiss of steam as the big seagate came down and closed over the stern. When the whistle shrilled, I was taken to my fathers cabin and set on the bunk above its built-in wooden drawers, across from the desk with his instruments, his charts, and his log, where even before the ship heaved away from the dock I drew a house with a stick mother and father and child beneath a spoked sun, which was another thing a good girl ought not have done. It was the captains log, a book for grown-ups, not childrens doodles, but it must have looked so dull, all those words on the page with no pictures. So I made that little gift for my father. Then the horn sounded, the engines sent a shudder up through the floor into my feet, and we went to the ice.