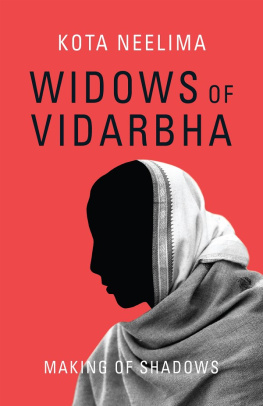

SHOES of the DEAD

By the same author:

Death of a Moneylender

Riverstones

First published in 2013

in RAINLIGHT by Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd.

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110002

Sales centres:

Allahabad Bengaluru Chennai

Hyderabad Jaipur Kathmandu

Kolkata Mumbai

Copyright Kota Neelima 2013

First impression 2013

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to any actual persons, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Kota Neelima asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Typeset in 11/14 pt Goudy Old Style by SRYA, New Delhi

Printed in India by

Rekha Printers Pvt. Ltd.

A-102/1, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-II,

New Delhi 110 020

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publisher's prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

To

my father

Authors Note

The trouble with writing a work of political fiction set in Delhi is that one cannot really name the people who have helped in the research. Instead, I would like to thank those who make Delhi one of the most academically intriguing, strategically dynamic and tactically mischievous cities of the world, as every great political capital should be.

The stories of the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra are the soul of this book. I thank the people of the districts of Yavatmal, Amaravati, Wardha and Chandrapur for the kindness and patience with which they have shared their experiences with me. These include farmers and farmers widows, taluka and district agriculture officers, officers incharge of relief and credit, resident and district collectors, managers of cooperative and rural banks, scientists and experts of research institutes, doctors of government hospitals, moneylenders and activists.

I thank my friend Anuj Parti for travelling with me to these districts and for documenting the stories through his photographs.

A principal premise for the book is that the best democracy is one that has the maximum capacity to evolve according to the needs and aspirations of the society. For insight into democratic politics and reforms, I am grateful to Dr Walter Andersen, senior diplomat and director, South Asia, SAIS, Johns Hopkins University, Washington, DC, who shared his knowledge and analyses which have been invaluable for me.

I have come to believe that like individuals, even nations can choose their destinies. For that belief, which is at the heart of this book, I would like to thank Dr Dinesh Singh, scholar, thinker and vice chancellor of Delhi University. The conversations with Dr Singh helped me realize that the search for a better destiny defines a nation, as it does an individual.

As a journalist, I have been fortunate to have worked with the best newspapers in India and with the finest of editors. I am grateful to M. J. Akbar, author and editor-in-chief of The Sunday Guardian , for helping me understand and report about the workings of the power templates of Delhi. I also thank him for allowing me time away from work to travel and write.

This book would not be complete without offering my special thanks to Namita Gokhale, scholar and author, for her belief in the concept of the book and for her constant support. Her views have deeply influenced my perspective and assessment of my own work.

This book would not have been possible without the guidance of Kapish Mehra of Rupa Publications. I am grateful for his vision for the book, his professionalism and his passion, and the way he supported the book at every turn. I thank Anurag Basnet for his brilliant and sensitive editing, and for perfect coordination between the two distant ends of the task, Delhi and Washington, DC.

I thank my assistants Shravan Prajapat and Sudhir Kumar for their efficiency with research, for operating across time zones and, most importantly, for always knowing where the missing papers might be.

This book is the result of the space and time granted by my family to my writing schedules and my travel for research. I thank them for making it possible.

Tuesday evening, the Kashinath residence, New Delhi

The November sunlight was like a gentle reminder of an old promise, touching the conscience hesitantly. For those in Delhi inoculated early in life against such evils as a conscience, it was just the month ahead of the winter session of Parliament, and the time to posture aggressively but slip quietly into the limelight.

Such political punctuations in the yearly calendar came in the form of exclusive gatherings of personal friends from the media organized by ambitious politicians. As even some of these carefully chosen journalists could still remain loyal to their profession, the younger politicians had to be often chaperoned and shielded from the freer elements of the press.

One such element, Nazar Prabhakar, parked his car outside the venue of one such exclusive gathering that evening. As he walked along the footpath, he observed the vehicles parked on the road; the labels on the windscreens gave him a fair idea of which of his colleagues he could expect at the meeting.

He walked in through the guarded gates of the government bungalow and was led to the garden behind the house over a narrow brick lane lined with early blooming winter flowers. He was certain that the choice and arrangement of the plants had been made by a government gardener who must have done this every year, irrespective of who lived in the house. Nazar felt that the flowers lost a bit of their charm if their blooming was merely procedural and probably approved by a director of the horticulture department.

But he realized, as he walked into the simmering, slant sunlight and the gentle mist on the grass, that it was not in everyones fortune to have the sun set in their backyard. The western horizon was one of the various heirlooms inherited by Keyur Kashinath.

Keyur was sitting among a circle of journalists, sharing a joke, the laughter soft and genuine. When he saw Nazar, he walked up to receive him and led him to a chair one place away from his own seat. They had met twice before but were yet to like each other.

Besides Nazar, there were five other journalists gathered in the small circle. From across, Sushila Lal, from an English-language television channel, smiled at him politely. In the chair next to him was Manohar Pandit, from a Hindi television network, and they shook hands. Next to Pandit was Girish Das, a friend who worked for a magazine. The only other newspaperman was Param Singh, a senior journalist and a friend of Keyurs father. As Nazar wished him good evening, Param nodded, the waning sunlight travelled through his silver hair, making it look almost golden.