First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Daniel Smith 2018

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78243-845-8 in hardback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78243-847-2 in ebook format

Image of the picture section: Sir George Reid, Sir Henry Duncan Littlejohn, 18261914. President of the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland.

Follow us on Twitter @OMaraBooks

www.mombooks.com

For Rosie, Charlotte and Ben

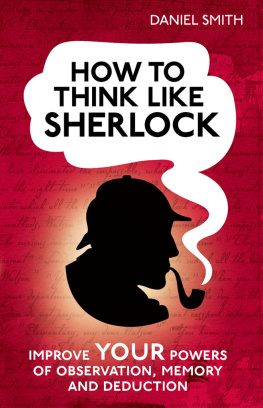

Contents

the lowest and vilest alleys in London do not present a more dreadful record of sin than does the smiling and beautiful countryside Think of the deeds of hellish cruelty, the hidden wickedness which may go on, year in, year out, in such places, and none the wiser.

Sherlock Holmes, The Adventure of the Copper Beeches

A RDLAMONT E STATE , A RGYLLSHIRE , S COTLAND

A UGUST 1893

It was no day to go hunting. Thunderclaps punctuated the incessant beat of the rain, lightning streaked across the sky and a Scotch mist hung over the land. But the three intrepid stalkers were not to be deterred.

At a little after 7 a.m., they left the comforts of Ardlamont House an oasis of Georgian splendour rising up amid hundreds of acres of rugged terrain on the Cowal Peninsula. The group was led by Alfred Monson, who had been living at the property since the beginning of the summer. His companions were a man known as Mr Scott, who had arrived at Ardlamont two days earlier, and a dashing young army lieutenant, Cecil Hambrough. Hambrough was just twenty years old and Monson a respectable rectors son with impeccable connections had been engaged by Cecils father to tutor the young man some three years earlier.

They were, perhaps, an unlikely looking group. Hambrough was the standout physical specimen. He stood over six-foot tall, strong and well built, with a firm jaw, blue eyes and a crown of blond hair. As the newspapers would later put it, he had beauty of the Saxon type. Monson, meanwhile, boasted an authentically aristocratic pedigree and was in the prime of life. Thirty-three years old and in fine shape, clean-shaven and well turned-out, he radiated an aura of intelligence and civility.

Scott, on the other hand, was rather less imposing. Introduced to the locals as an engineer from London, he dressed neatly enough a bowler hat sat proudly on top of his head but he nonetheless seemed a little rough around the edges. There was something imponderable about Mr Scott, so that those who encountered him on this trip were unsure as to quite what to make of him. Perhaps it was his lack of ease in the grand surroundings of Ardlamont, his slightly straggly moustache or the way he dropped his aitches. Whatever it was, he did not seem to fit the then commonly held image of a gentleman.

Mrs Monson, her three young children and their governess had left Ardlamont by boat for Glasgow early that morning. The three men had all risen shortly afterwards despite their previous nights misadventure. A moonlit fishing trip on Ardlamont Bay had only narrowly avoided tragedy when the boat that Monson and Hambrough had taken out sprang a leak. The two were forced to swim for their lives. Yet, despite the danger they had faced, they along with Scott, who had remained on shore returned to the house in good spirits, toasting their safe return long into the night.

When Wright the butler got up just after seven, he had found Hambrough in the dining room and served him a glass of milk and a biscuit. A little later, Monson, Hambrough and Scott left for their mornings sport. They walked along a road by the house, then climbed into a field and from there entered the surrounding wood. They were spread out in a line as if intent on beating for rabbits.

Around nine oclock, Wright encountered Monson and Scott back in the house, standing at the dining-room door. Neither of them had their gun, but Scott was carrying several rabbits that he said Hambrough had shot. Then Monson told Wright that their young companion had also shot himself. In the arm, sir? enquired the butler nervously. No, came the reply. In the head. He was, Monson explained, lying out in the woods. Quite dead.

Guided by Monson, the appalled Wright went to view the scene of the calamity, picking up Whyte the gardener and Carmichael the coachman along the way. They discovered Hambroughs corpse on top of a dyke by a ditch. His head was leant against his left shoulder, blood oozing from a wound behind his right ear and soaking into the ground behind. His right arm lay at his side, while his left rested across his chest. What should we do? asked Monson agitatedly.

We had better send for a doctor, the butler replied, stony-faced.

Then Wright, Whyte and Carmichael contrived to move the body in a rolled-up rug out of the woods and back to the field, from where it was driven by cart to the house. Back indoors, Wright helped dress the body ahead of the arrival of the local GP. It seemed like the right thing to do a nod to decorum in the face of the tumult prompted by such a grisly and sudden death.

Among aficionados of the then blossoming genre of crime fiction, the mysterious death of Cecil Hambrough might have evoked memories of a story featuring the most famous literary detective of all time, Sherlock Holmes. Two years earlier, the Strand Magazine had published Arthur Conan Doyles Holmes adventure The Boscombe Valley Mystery. It featured a young man who reported the death of his father in whose company he had recently been his body stretched out upon the grass in a wood. But whereas the son was quickly arrested on suspicion of murder and the location of death treated as a crime scene, at Ardlamont there was an assumption that Cecil Hambroughs death was an accident. With scant regard for the preservation of potential evidence, so began one of the most notorious cases of the Victorian age an enduring mystery that wreaked havoc in the lives of all its main actors and a good many others besides.

Prominent among them were two upstanding citizens of Edinburgh, both of them leading figures in the medical world and pioneers of forensic science Dr Joseph Bell and Dr Henry Littlejohn. Moreover, these two were, as chance would have it, the chief inspirations behind the creation of Sherlock Holmes. Brought in to investigate the case far later than Holmes would have ever appreciated, they nonetheless proceeded to deliver vital evidence as to what had gone on at Ardlamont. The death of Cecil Hambrough would pitch the pair into a furious battle between reason and knowledge on the one hand, and doubt and the dark heart of man on the other. It was a real-life playing out of the struggle that Doyle had Sherlock Holmes wage countless time over his illustrious fictional career.

A mystery as perplexing as any Holmes ever faced, the Ardlamont affair established Bell and Littlejohn as the definitive link between the imagined, gas-lit world of 221b Baker Street and the thrilling frontiers of real-world criminal investigation in what was the first golden age of forensic sleuthing. This being real life, however, the stakes were for everyone far higher.