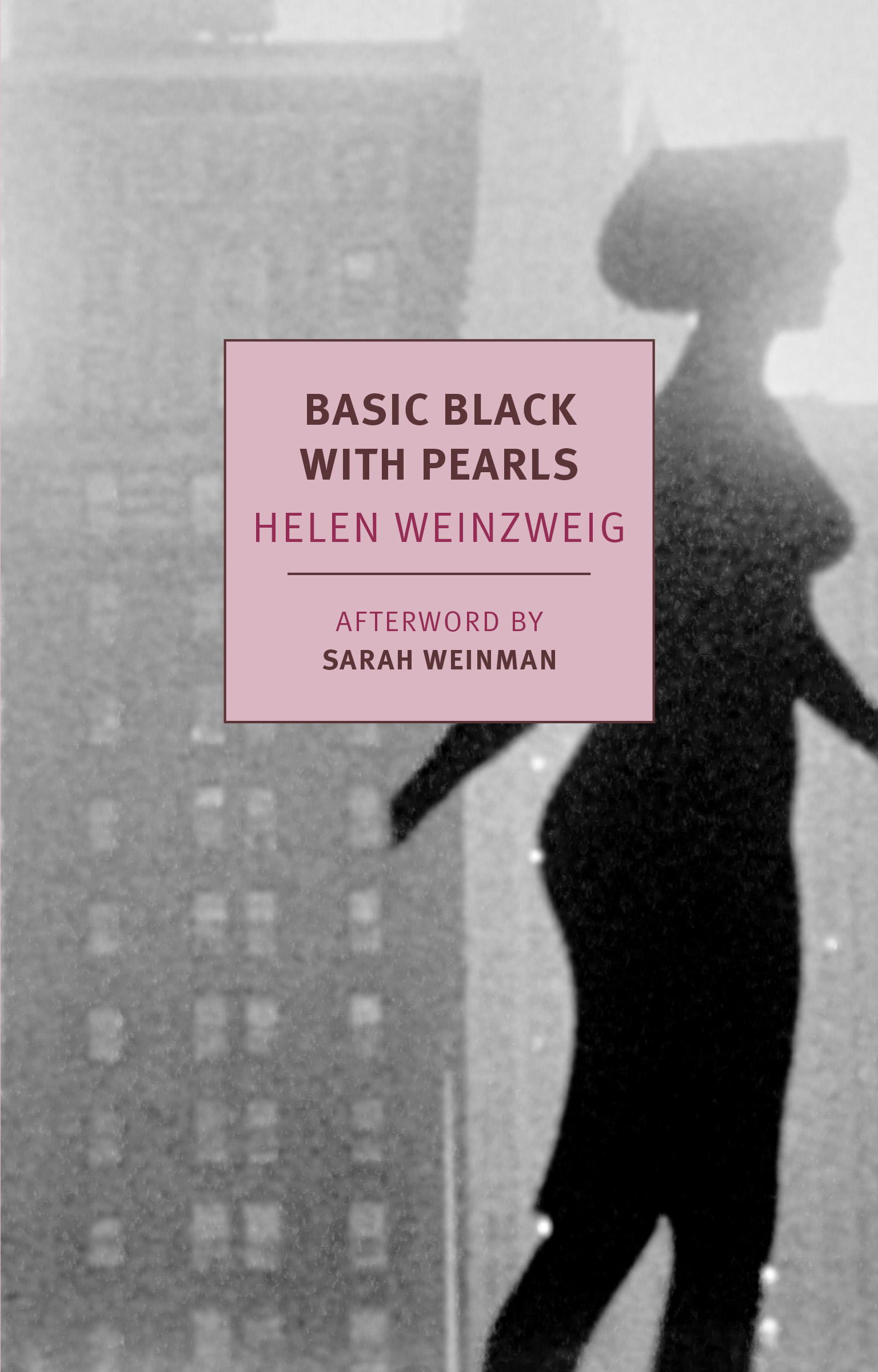

AFTERWORD

W HEN I FIRST read Helen Weinzweigs Basic Black with Pearls several years ago, I emerged in the sort of daze that happens when a book seems to ferret out your most secret thoughts and hopes. Since then Ive described the book to others as an interior feminist espionage novel. That is, of course, a reductive way to look at this work, which is so much more than that single phrase can express. And yet those four words, taken together, suggest the scope and the breadth, the daring and the audacity, the humor and the pathos contained in a work of less than one hundred and fifty pages. It was a novel I did not know I was looking for, but finding it was a revelation.

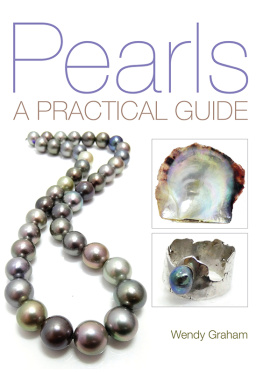

The interior nature of Basic Black is central to its unfolding. Shirley Kaszenbowski, regarded from the outside, is the embodiment of the invisible woman. She is in her early forties, long-married with two children. She wanders through Toronto in the titular basic black dress, a strand of pearls around her neck, cloaked by a tweed coatdesigned to last for decadesfrom the citys most expensive, most fashionable, and snobbiest department store. I fool no one, Shirley admits. I am regarded as a woman with no apparent purpose, offering no reason for my presence. Regarded from inside, however, Shirley is anything but purposeless. She is aglow. Her appearance, her age, her station is a cloak for a rich life of travel, adventure, and meaning. As the critic Art Seidenbaum noted in his review for the Los Angeles Times, her odyssey is erotic, but her appearance is prosaic.

What seems like aimless shopping and fruitless wandering is cover for Shirleys ongoing search for her lover, Coenraad. He fills her with a sense of longing and purpose that her husband, Zbigniew, cannot: When I see that stance of Coenraads all fears disappear: babies dont die, cars dont collide, planes fly on course, muzak is silenced, certitude reigns. That is how I always recognize my love: the way he stands, the way I feel. By contrast, Zbigniews weekly routine conjures up an opposite image: I was thinking particularly of Sundays at home when Zbigniew comes back from the stables, hangs up his riding crop beside the mantel-piece and settles in with the weeks newspapers. So long have Sundays made Shirley shudder that adultery is a refuge.

Then again, we only have Shirleys word for whats happened. That uncertainty will prove critical later.

Masks and costumes suffuse the narrative of Basic Black with Pearls. Shirleys exterior life as a housewife and mother is also a disguise, which is why its critical to look at the feminist and espionage parts in tandem.

Basic Black with Pearls contains overt references to Virginia Woolf and covert ones to feminist classics like Kate Chopins The Awakening and Charlotte Perkins Gilmans The Yellow Wallpaper. The scholar Ruth Panofsky, who wrote extensively about Weinzweig, sees echoes of George Eliot. Others have compared Weinzweig to the Canadian Margarets: Laurence and Atwood. I, however, see resonances and overtones in a novel published eight years after Basic Black: David Marksons Wittgensteins Mistress. Weinzweig kept a copy of Marksons 1988 novel in her personal library, which makes me think she recognized some kinship with her own work. (Whether Markson read Weinzweig is less clear.)

These novels describe women not only breaking away from conventions, but also filled with desire and ambition that are almost too much to bear, a secret from themselves. Weinzweig had to search out these books to counteract decades of reading male-dominated narratives, which she needed to reject to construct her own style. One of the things I had to learn after reading all this male fiction was, what do I as a woman feel like, she said in a 1990 interview. All the literary forms were mens, all the philosophies were mens philosophies.... I had to translate these forms into the female.

Shirleys lover, Coenraad, appears to be some kind of spy with a nebulous organization known as The Agency. Often Shirley meets himin Vienna, Paris, or closer to home. Coenraad and I have a code for our meetings, taking the printed word and interpreting it according to mathematical formulae. A specific volume of National Geographic is equal parts clue and inspiration.

Coenraad, at nearly every turn, wears a disguise, cloaking his face, his manner. He appears as a downtown wino, a derelict in prop clothes, in a stained green jacket, too long in the sleeves, loose trousers held up somehow. They dont speak much in public because he must be on the qui vive at all times, and I because his presence renders me speechless.

Shirley, too, adopts disguises. Her married name of Kaszenbowski supersedes her maiden name of Silverberg. She also takes on the name Lola Montezthe pseudonym for the real-life Victorian-era ballet dancer and actress Maria Dolores Eliza Ros-anna Gilbertwhen checking into hotels for her latest assignation with Coenraad. Weinzweig uses humor as a cudgel, a tension breaker, a means of complicating the narrative. Humor also deflects attention from the woman underneath Shirleys oh-so-proper costume. Zbigniews rigid Sunday routine fills her with dread, and yet, moments after identifying her revulsion, Shirley thinks: I live in a nice house, you know. My house is in a nice part of Toronto. I hate disorder.... I miss putting things in order.

This vacillation between order and chaos at home hints at Shirleys greatest mask: sanity. Basic Black with Pearls dances on the edge of it, leaving the reader to wonder whether madness, be it schizophrenia or some other disorder, may be the most logical explanation of the story she is trying to tell. (At one point she discovers Zbigniew reading a newspaper article about her admittance to a hospital: She claimed to have neither husband, children or other family; nor did she have a family physician.)

Weinzweig, however, is too astute to slide into platitudes when there are more pressing liminal spaces to mine. It seems to me that in a confusion of extremes one either lies or tells the truth, whichever works best, Shirley says. Up until now the risk of deceit has, for me, been greater than the risk of truth.

Basic Black with Pearls, upon its publication in 1980, was greeted with a mix of praise and misunderstanding. Critics sensed its daring and applauded its formal inventiveness, but those qualities also kept people at bay. One newspaper review from my hometown of Ottawa, Canada, castigated the novel for being a writers book, not a readers book, the illegitimate offspring of Franz Kafka, and too good to accommodate the present level of Canadian culture. In other words, CanLit wasnt supposed to be written this way.

In fact, Weinzweig didnt draw on Canadian literature, largely preferring European writers, often not of prose. She had previously published several short stories and a novel, Passing Ceremony (1973). Ostensibly about a wedding and the guests in attendance, Passing Ceremony is far more about the nature of coupling and decoupling and the madness and anxiety that exists in between those two states. Weinzweig drew from the work of Alain Robbe-Grillet, Samuel Beckett, and Nathalie Sarraute for the short prose sections, some as short as a single line.

Mid-twentieth-century European literature does not provide the entire answer to the question of influence. Weinzweigs Jewish upbringing is part of the equation as well. She told her original book editor to read The Joys of Yiddish; the mourners Kaddish is directly referenced in Basic Black with Pearls.

The jagged rhythm of Passing Ceremony