Table of Contents

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE CLASSIC TEN

Nancy MacDonell Smith is the fashion news/ features director at NYLON magazine. She has written about fashion and style for The New York Times, Harpers Bazaar, Wallpaper, and New York magazine. She was born in Montreal and now lives in New York City. The Classic Ten is her first book.

For my mother

MY HEARTFELT THANKS GO TO STPHANIE ABOU, MY agent, and Ann Mah, my editor, who believed in The Classic Ten from the moment I told them about it. Their unstinting support made this book possible. I would also like to thank two great teachers: Susie Linfield, for her insistence on ruthless specificity, and Anne Matthews, for her endorsement of what was then the tiniest glimmer of an idea. Every writer needs good friends, and Im blessed with many; I would particularly like to thank Annie Sommers, one of the first readers and fans of The Classic Ten. And finally, I would like to thank my family for their love and encouragement. This couldnt have happened without you.

Introduction

THE IDEA FOR THE CLASSIC TEN WAS BORN DURING A discussion with a professor who remarked apropos of nothing at all, Have you ever thought of writing about fashion? Youd be good at it. I hadnt thought of it, but the suggestion not only charmed me, it made perfect sense. I spend an inordinate amount of thought and money on clothing, and this is a perfect way to justify my zeal; its a glorious world when a new pair of shoes can be classified as research. Though I have occasional twinges of guilt about the supposed superficiality of my subject, I cant deny that my interest in it is deep and abiding. I blame this on early exposure to beautiful clothes. When I was very small, my father would return from trips to Europe with bags of clothes and shoes for my motherlovely soft Italian knits and gleaming leather T-straps in delicious colors. I was hooked.

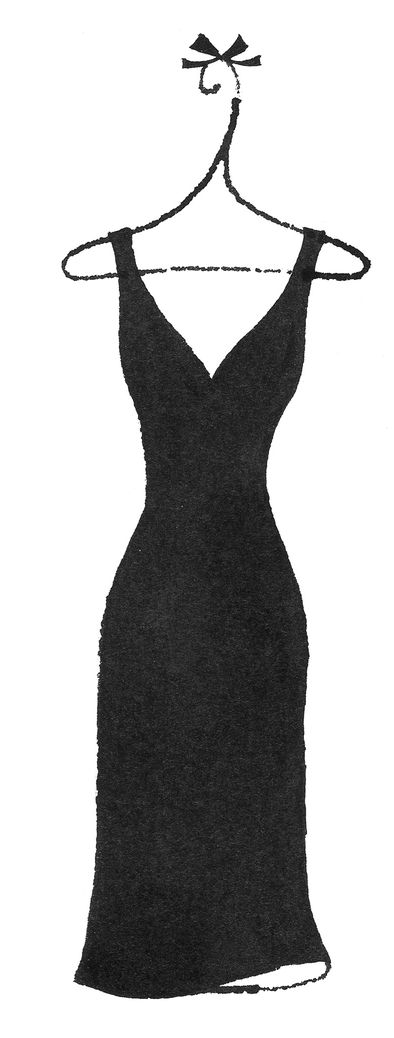

But far more than necklines or heel shapes, the meaning of what we wear intrigues me, particularly that of those clothes that have transcended fashion to claim icon status. The little black dress, the white shirt, the cashmere sweater, jeans, high heels, pearls, lipstick, sneakers, the suit, and the trench coat are not just garments, theyre symbols that resonate across social and cultural boundaries. Their origins may be centuries old, but their meanings still ring true, because the ideas they representsexual allure, wealth, power, rebellionare universal and persistent. Pearls symbolize purity, virtue, and artless perfection, while jeans are emblematic of self-expression, rock n roll, and democracy. We all recognize this, just as we recognize that green means go and an olive branch signifies peace.

One reason that were fluent in the meaning of these iconic pieces is that so many famous fashion images are built on them. Think of Audrey Hepburn staring into Tiffanys window, the personification of chic in a little black dress by Givenchy, or Marlene Dietrich smoldering in a 1930s publicity shot, wearing a man-tailored suit and a perfectly angled beret. Picture Jackie Kennedy, young and patrician-looking, in a white shirt and capris, romping on a sunlit lawn with her children, or a blue jean-clad Brooke Shields asserting that nothing came between her and her Calvins. All of these images have one thing in common: They include an iconic item of clothing. Moreover, its the iconic itemsthe little black dress, the suit, the white shirt, and the jeansthat lend these images a sizable portion of their power. We immediately recognize the clothes in these photos, and we can read the myriad messages they transmit in the blink of an eye. Hepburn would not have looked nearly as memorable if she were eyeing diamonds in a duffle coat; nor would Dietrichs sexuality be as sizzling if she wore straightforward evening gowns. The little black dress, with its roots in mourning and its faint whiff of malevolence, instantly conveys an experienced worldliness; the pearls add class. The suit, so obviously borrowed from menswear, throws Dietrichs femininity into the fore so that its impossible to disregard.

Every item of clothing has a narrative. Some of their narratives carry greater weight, have a deeper meaning, and a more lasting influence than others. This is the story of those items.

The Little Black Dress

Women who wear black lead colorful lives.

Neiman Marcus ad

IN ONE OF THE DELICATELY CALIBRATED SCENES IN Edith Whartons The Age of Innocence, a society matron offers this biting analysis of Ellen Olenska, who has shocked 1870s New York society by her decision to divorce her husband: What can you expect of a girl who was allowed to wear black satin at her coming-out ball?

What, indeed? As Mrs. Archers remark suggests, the woman in black is always suspect. Black implies you have something to hide, such as a colorful past. Its a provocative color, one few people are indifferent to. Age-old associations link it with death, evil, and destruction. Wearing black implies transgression. Anna Karenina wore black to the ball at which Vronsky became smitten with her; her niece, Kitty, herself in love with Vronsky, wore pale pinkand failed utterly to get his attention. When a woman puts on a black dress, the world assumes shes sophisticated, sexual, and knowing. By eschewing the bright plumage of the hunted for the discreet attire of the hunter the woman in black is taking on the role of the aggressor. In pastels, shes a target, passive. In black, shes charting her own course.

Seventy-five years after Whartons fictional black gown horrified New Yorkers, Cornell Woolrich, the great pulp novelist of the 1940s, used black to turn a traditional symbol of womanhood, the bride in her white gown, into an apocalyptic vision. In The Bride Wore Black, Woolrichs bride, widowed on her wedding day by a car full of drunks as she and husband descended the steps of the church, is an avenging fury. She tracks down every man responsible for her husbands death, bewitches him, then kills him. In the film version Jeanne Moreau plays the bride, stalking the streets in a little black dress by Chanel, the designer who did more than any other to put women in this emphatic color.

In Ellen Olenskas time, no man wanted to marry a woman bold enough to choose black as her signature color (Ellen meets her husband not at her debut but in far less puritanical Europe, and Wharton insinuates that he is so singularly debauched that he might very well have been drawn to a girl in black) and the point of the coming-out ball was to launch debutantes into the marriage market. Yet Ellen fascinates every other character in the novel. No one remembers the white dresses of the other girls, while Ellens raven toilette remains etched in memory. Thats not surprisingblack is most effective when it is surrounded by less passionate shades. Ellens black dress symbolizes her individuality, her determination to live her life on her own terms.

Its an appealing concept, and one that has drawn generations of women to the little black dress. Indeed, the term has entered our cultural lexicon. Say it and everyone knows what youre referring to: a dress thats simple enough to appear effortless, yet elegant enough to mark the wearer as a woman of taste.