A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion

General Editor: Susan Vincent

Volume 1

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in Antiquity

Edited by Mary Harlow

Volume 2

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Medieval Age

Edited by Sarah-Grace Heller

Volume 3

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Renaissance

Edited by Elizabeth Currie

Volume 4

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Age of Enlightenment

Edited by Peter McNeil

Volume 5

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Age of Empire

Edited by Denise Amy Baxter

Volume 6

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Modern Age

Edited by Alexandra Palmer

A CULTURAL HISTORY OF DRESS AND FASHION

VOLUME 4

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

| 50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

| London | New York |

| WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

| UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2017

Reprinted 2018

Bloomsbury Publishing 2017

Peter McNeil has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Editor of this work.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing- in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: HB: 978-0-8578-5761-3

HB set: 978-1-4725-5749-0

EB set: 978-1-3501-1411-1

Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

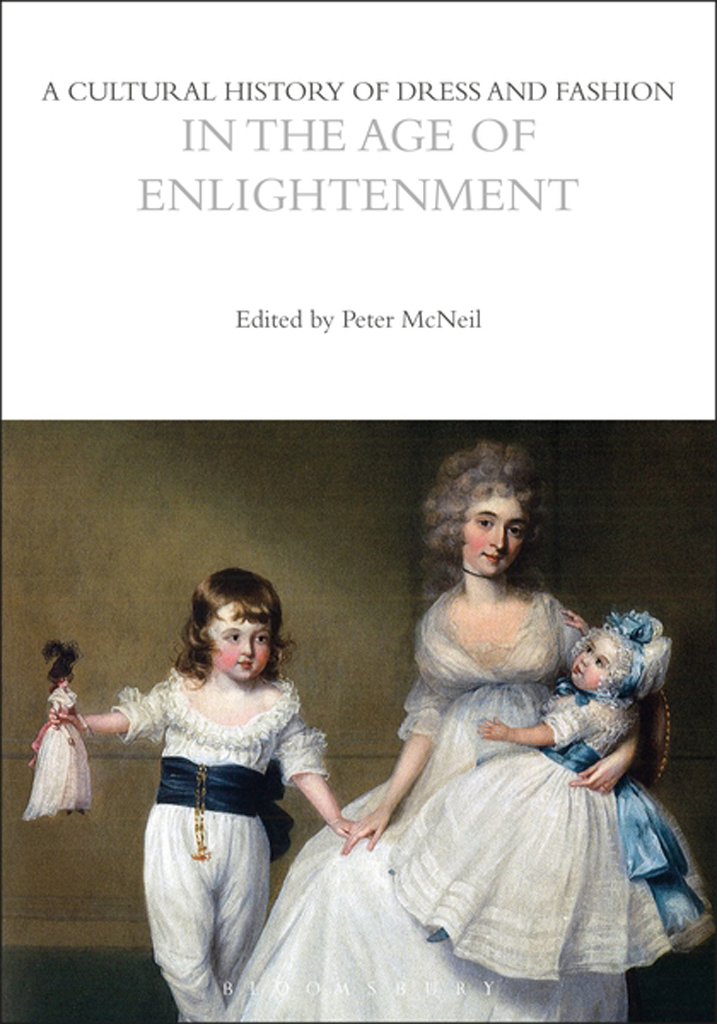

Cover design: Sharon Mah

Cover image by Frances Alleyne. Courtesy of Richard Green Gallery, London.

CONTENTS

Peter McNeil

Tove Engelhardt Mathiassen

Beverly Lemire

Isabelle Paresys

Dagmar Freist

Dominic Janes

Mikkel Venborg Pedersen

Barbara Lasic

Christian Huck

Alicia Kerfoot

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

PETER McNEIL

Fashion: custom, usage, manner of dressing, of adjusting oneself, in a word, everything that serves the parure and of luxury; therefore fashion can be considered politically and philosophically.

D. de Jaucourt, Encyclopdie, 1765.

Fashion may be considered in general as the custom of the great.

It is the dress, the furniture, the language, the manners of the great world.

Which constitute what is called the Fashion in each of these articles,

And which the rest of mankind are in such haste to adopt,

After their example.

A. Alison, Of the Nature of the Emotions of Sublimity and Beauty, 1790.

Aileen Ribeiro, in her magisterial publication The Art of Dress, cited two authors, one eighteenth-century French and one British, to demonstrate that considering fashion and dress to be a part of cultural, philosophical or even scientific change was considered plausible at the very time the fashions were made and consumed. Contained in these short quotations are many of the ideas that would color future theoretical speculation by the likes of late nineteenth- and twentieth-century writers such as Thorstein Veblen and even Pierre Bourdieu: that fashion is something that stretches to encompass much more than sartorial fashions, that fashion is hastily copied, and that it also serves to identify and situate individuals and societies. In the expression adjusting oneself there is even contained the suggestion of the embodiment which has come to provide new impetus in writing about fashion in recent years. I will take these three themes to structure my overview of dress during the Enlightenment: the fairly elastic definition of fashion that pertained during the long eighteenth century, the uptake, diffusion or indeed, rejection, of fashions by individuals and groups, including rural lites, and the relationship of dress and the body to Richard Sennetts famous formulation of interlinked flesh and stone, that is, the linking of dress, body and the built environment in the rapidly transforming towns and cities of eighteenth-century West Europe.

LOOKING AT FASHION: PRIORITIZING THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

The relatively large survival rates of the dress of the lites compared with that of demotic dress creates various distortions in studying the field of fashion history.archeologist or ethnologist, the antiquarian, the stylist (photographer Cecil Beaton, for example, in the 1970s), or the connoisseur (Diana Vreeland).

Nineteenth-century essayists thought fashion to be central to zeitgeist. Charles Baudelaires mid-nineteenth-century opinion regarding the significance of fashion as extracting an essential jus concerning past and present is well known. Hippolyte Taine used a similar approach in arguing why fashion mattered: I go up to Estampes [the print collection of the Bibliothque National] and I looked at the sixteenth century masters... A fold of clothing is a trace of passion like an epithet. I endeavoured to rediscover and to experience those of the sixteenth century. Taine, visiting the famous connoisseurs of firstly the French rococo and later Chinese art, the Goncourts brothers, in 1863, examined their eighteenth-century engravings:

Nothing teaches history better. It seems that one comes straight from living in the century. The fineness, the gaiety, the taste of pleasure, these three gifts beget the rest. Nothing as delicious as these toilettes, these levers [risings in the morning] of pretty naked women with the large embroidered curtained beds. These pretty gilded and turned furnishings... Its the cuisine of pleasure. Its the genuine France.

This delicious and erotic aspect of eighteenth-century costume, as well as its temporal distance from the late nineteenth century [it was then barely antique or one hundred years old], made it popular when it began to be collected. The late nineteenth century witnessed a veritable explosion of interest in the eighteenth-century woman., and the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada (established 1912, where the founding archeologist director, Charles T. Currelly, collected broadly within categories such as Islamic art, which included textile culture). The majority of the garments collected at such institutions, with the exception of non-Western dress, were the clothes of the upper classes or lites, in part because they were made of splendid or intricate materials that delighted and challenged viewers and makers to emulate their aesthetics and skills. Many more womens than mens clothes were collected, although eighteenth-century mens silk suits and embroidered waistcoats were numerous in museum collections, probably because they looked so very different from the dark nineteenth-century suit. Others had personal connotations, with many old labels (some apocryphal) claiming that they were wedding suits. Suits for presentation at court also rank as high purported survivals.