A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion

General Editor: Susan Vincent

Volume 1

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in Antiquity

Edited by Mary Harlow

Volume 2

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Medieval Age

Edited by Sarah-Grace Heller

Volume 3

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Renaissance

Edited by Elizabeth Currie

Volume 4

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Age of Enlightenment

Edited by Peter McNeil

Volume 5

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Age of Empire

Edited by Denise Amy Baxter

Volume 6

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Modern Age

Edited by Alexandra Palmer

A CULTURAL HISTORY OF DRESS AND FASHION

VOLUME 2

CONTENTS

Sarah-Grace Heller

Elizabeth Coatsworth and Gale R. Owen-Crocker

Eva Andersson Strand and Sarah-Grace Heller

Guillemette Bolens and Sarah Brazil

Andrea Denny-Brown

E. Jane Burns

Laurel Ann Wilson

Michle Hayeur Smith

Dsire Koslin

Monica L. Wright

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

SARAH-GRACE HELLER

Fashion in a medieval age, is that even possible? Werent those centuries the Dark Ages? the antithesis of the dazzling world of catwalks and designer labels?

These are questions worth debating. Fashion, Medieval, and Dark Ages are lenses for interpreting human experiences and the traces they leave. As lenses, they are capable of bringing certain things into focus; equally capable of distortion. The medieval sources are always fragmentary. From bones to books to damaged frescoes, they all require significant interpretation to derive information about medieval material culture and how people felt about it. Lenses, in short, are necessary, but also intrinsically limit the field of vision: we must proceed aware of limits and potential slants.

Fashion is a universal term for some, signifying simply the human impulse toward adornment, present even for our Neolithic ancestors. As such, it was unquestionably present through the periods we term the European Middle Ages, when all types of records attest desires for jewelry, rich cloth, and color. The noun fashion denotes work performed on an object to shape it, pattern it, personalize it. In English, it comes to connote the manners and customs of a land around the end of the medieval period, in the late fifteenth century. The French mode, similarly, can signify the way either an individual or a group does something. Philosophers begin wondering why the French dress la mode des Franaisconstantly changing their minds about what to wear, as Montaigne observesaround the sixteenth century. From these early modern lexical moments, fashion would evolve into its own field of journalism. In the medieval period, however, certain habits of modern fashion systems are already in effect, in certain milieus: there were seasonal cycles of wardrobe renewal, changing styles, efforts to use appearance to attract others, and to increase ones influence.

Some theorists see fashion, or more specifically Modern Western Fashion, as a historical phenomenon with a specific and unique evolutionary trajectory. This view is predicated on the idea that societies operate differently with regard to clothing and ornament. Fashion demands attitudes and industries supporting constant change, continuous new consumption, and outmoding of styles before they are worn out. Cultures in which there are no surpluses, where innovation is hampered, or change discouraged would not be fashionable in the manner that the West has become.

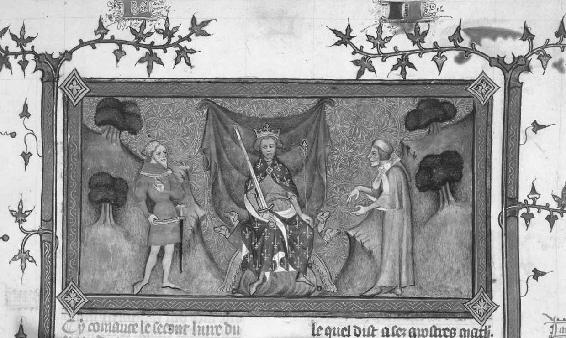

Dating the birth of Western Fashion based on visual sources, Paul Post observed what he termed a revolution in mens dress in the mid-fourteenth century. After centuries of preferring longer robes, men began wearing short doublets and showing ample expanses of leg).

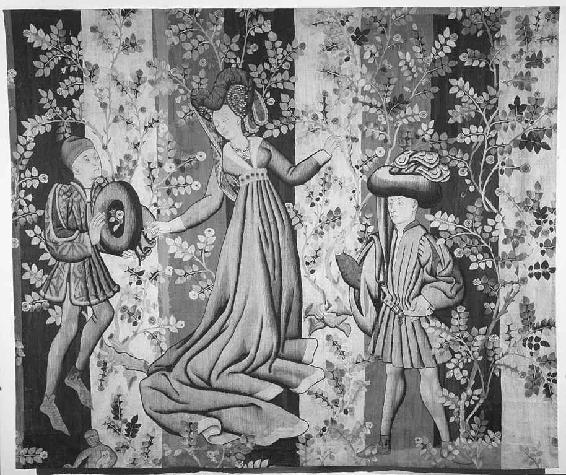

Along with this style change, the steadily more numerous illustrations show more and more variety and exaggeration in cuts and embellishments. The premise that Western Fashion began in the fourteenth century has become a commonplace for many.).

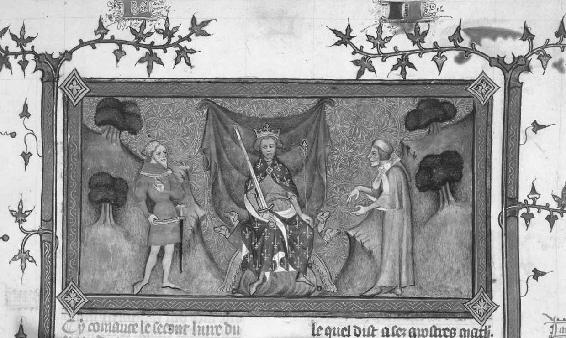

FIGURE 0.1: A fashionable knight in the new style for shorter robes, a wasp waist, and pointed shoes debates with a cleric in long robes as the king, also in long stately robes, adjudicates, from Le Songe du Vergier, Paris c. 1378. Royal 19 C IV, f. 154. British Library.

There is a long tradition of viewing the empires of antiquity and the Dark Ages as the antithesis of fashion. Some archeologists, in contrast, have comfortably used the term fashion (mode) to describe the regular changes observable in the jewelry styles of the early Middle Ages. As scholars probe the pre-fourteenth-century evidence with the lenses and tools of fashion, there is much to find worth discussing.

This volume will address fashion from both perspectives. The essays ask how people dressed, and how they made and/or purchased the materials necessary and desired for their personal adornment. They will also probe attitudes toward the fashionability of clothing and consumption. They explore centers of creativity and production. In some cases, they also describe the disappearances of these places, as cultures and languages changed, borders were redrawn, and trade routes shifted due to calamity or competition.

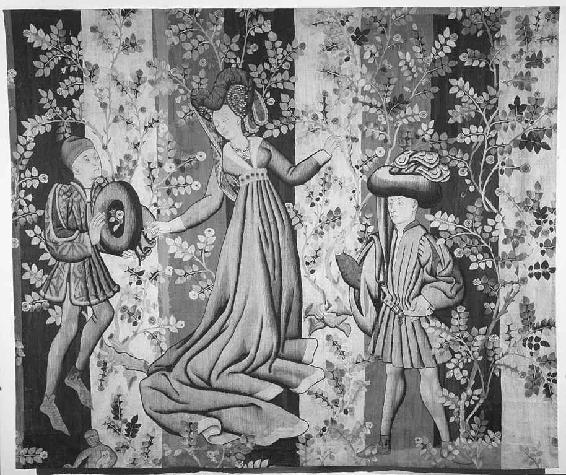

FIGURE 0.2: A fashionable variety of cuts, exaggeration of styles, and sumptuous fabrics are clearly visible on the courtiers depicted in this Flemish tapestry c. 144050. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

SOURCES AND DISCIPLINES

It is not particularly easy for medievalists to describe clothing or attitudes about consumption effectively. They cannot consult a continuous run of fashion magazines for the millennium or so associated with this period and observe the annual changes. Written sources are composed in dead languages, preserved in books usually copied decades or centuries after the works were composed, with all of the attendant potential for mistakes, and which have often only survived the ravages of the intervening centuries (the regular cycles of town fires, floods, mobs burning public buildings, bombing campaigns, etc.) by wild chance and the protective zeal of bibliophiles. Some medievalists examining fashion come from university language departments and history units. Such scholars are trained to read, analyze, and compare Latin and early vernacular texts, which requires rather significant philological preparation and capacity for mental acrobatics to interpret the fluctuating spellings, dialectal variations, and evolving grammar systems of these periods. Terms for dress are often hapax legomena, words only occurring once in the extant texts, presenting lexical quandaries. Latin is present throughout the millennium, used for legal and official documents, notarial records, saints lives, poems, sermons, and treatises. Vernacular texts only begin to appear in profusion around the seventh to ninth centuries for Anglo-Saxon and Old High German; in the twelfth century for Old French, Occitan, Catalan, Castilian, Middle High German, and Old Norse laws; the thirteenth for Galician-Portuguese, Scanian (Danish), and Sicilian; the fourteenth for Middle English and Dantes Tuscan. Certain languages are less studied, partly as a result of the size of teaching faculties (the Old and Middle English specialists are far more numerous than the Old French, Dutch, German, Catalan, Castilian, Italian, and so on, due to the prominence of English departments in the Anglophone world). The current national lines are not necessarily those of the Middle Ages, either. (Universities have no Sicilian or Frisian units these days.) Philologists, lexicographers, and historians of dress often find it difficult to leave their linguistic and national silos.

Next page