A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion

General Editor: Susan Vincent

Volume 1

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in Antiquity

Edited by Mary Harlow

Volume 2

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Medieval Age

Edited by Sarah-Grace Heller

Volume 3

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Renaissance

Edited by Elizabeth Currie

Volume 4

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Age of Enlightenment

Edited by Peter McNeil

Volume 5

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Age of Empire

Edited by Denise Amy Baxter

Volume 6

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Modern Age

Edited by Alexandra Palmer

A CULTURAL HISTORY OF DRESS AND FASHION

VOLUME 3

ELIZABETH CURRIE

An Italian traveler to London at the end of the fifteenth century reported that the English dressed in a clumsy imitation of French fashions. It was a dual criticism, implying that the English not only chose to copy the clothing of another country but also that the end result was decidedly inferior. Despite exhibiting a keen understanding of different nations fashions and living in a world increasingly connected by goods, Harrison considered it treacherous of his fellow countrymen to adopt such clothing. It denoted instability and subjugation, as well as constituting a betrayal of local products.

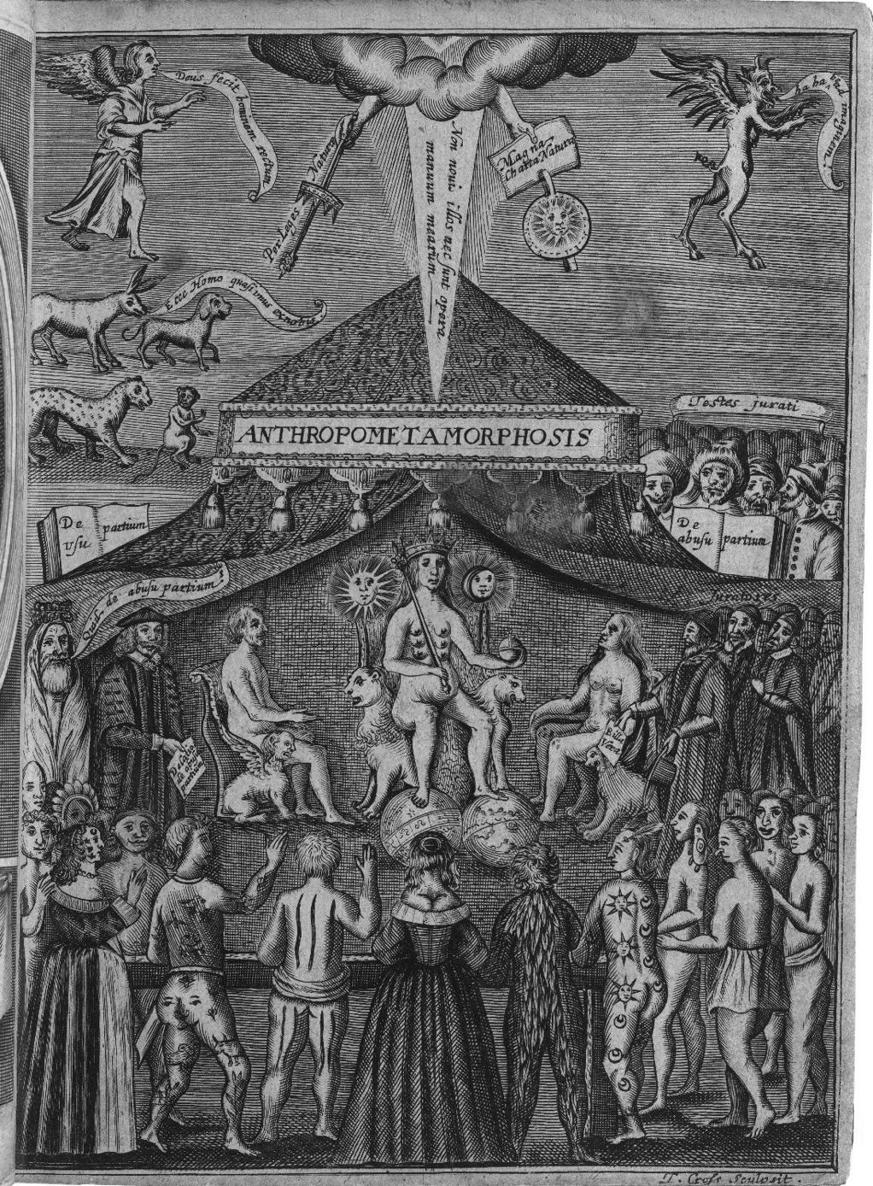

The print revolution of the fifteenth century played a vital role in propagating such strident views on the cultural and political significance of clothing. It ensured the increasing circulation of fashion through word and image, with many different texts dealing with clothing, from prescriptive writings, manuals on etiquette and domestic management, to travel accounts and festival books. The politics of display, morality, gender, status, and authority were reflected in and through clothing, prompting a growing awareness of the implications of sartorial nuances. The issues that feature repeatedly in these very disparate sources shed light on some of the different kinds of identities, including sexual, geographical, and political ones, all bound up in dress. Discussions surrounding fashion became more sophisticated and insistent, just as the garments themselves became more complicated, structured, tailored, layered, laced, hooked, and pinned into place. By the sixteenth century, fashionable outfits required careful deciphering to understand their many parts, a view shared by contemporary commentators who dissected their individual components one by one, speaking about the clothed body using the same language found in scientific and medical treatises, in which the body itself was often seen as pieced together.

Many cultural forms in the Renaissance examined new ways of thinking about the world, and what it meant to be human, through clothing. Some were influenced by the voyages of discovery pioneered largely by Portuguese and Spanish explorers from the latter part of fifteenth century onwards, to the West Coast of Africa, the Indies, and subsequently America. In the printed costume books that became popular during the second half of the sixteenth century, dress was a mechanism for organizing the entire world, for categorizing and sometimes subordinating other cultures. Kristen Ina Grimes has analyzed the use of dress to map the globe, pointing out the similarities between costume books and cartography, both relying on the interplay of the strange and the familiar.).

FIGURE 0.1: Usher to the Grand Selim with Parrots, Jacopo Ligozzi, brush and gouache on vellum, c. 15805. Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images.

FIGURE 0.2: John Bulwer, Anthropometamorphosis: Man Transformed (London: William Hunt, 1653), title page. Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC.

Clothing is relevant to all the major historical debates of the period and this is reflected in the interdisciplinary nature of the scholarship. Of vital importance are the researchers and practitioners, including theatrical and historical dress costumers, conservators, and curators, who foreground object-based research, viewing clothing and textiles as historic documents. Scholars from the fields of archaeology and anthropology, economics, gender and literary studies, histories of art and philosophy, have increasingly engaged with early modern dress, resulting in very diverse and potentially complementary approaches. We are lucky to have a growing range of sources for the study of fashion from this period. Archival documents are more detailed and some accessories and garments survive, although still very limited in their range and number. This has facilitated various innovative, multi-disciplinary studies and research questions that have moved beyond traditional concerns of conspicuous consumption and normative behaviors to investigate ideas about agency and varied social behaviors and experiences. These are discussed in this volume, which reveals dresss potential to absorb, reflect, and shape a changing spectrum of cultural practices in the early modern period across different themes. This introduction outlines some of the defining features of the contemporary clothing system, such as how, where, and why fashion thrived, and how dress and appearances intersected with cultural constructions of gender and selfhood. In so doing, it highlights concerns that currently shape the study of early modern clothing, while providing a framework for the subjects elaborated in the subsequent chapters.

PERCEIVING THE WORLD THROUGH DRESS

The certainty that dress could act as a mechanism of control, because of its ability to relay fundamental information about the wearer, such as social status, gender, or political beliefs, was deeply embedded throughout this period. As a consequence, clothing had the potential to keep people in their place. It could bind individuals into a carefully structured hierarchy, defining the way they interacted with those around them. As most early modern societies placed great emphasis on rank and genealogical pedigree, dress was a vital touchstone. Peter Stallybrass and Ann Rosalind Jones have described Renaissance garments as acting as the bearer of names, and we can see high-status individuals literally marking themselves with clothing, as illustrated by Maria Portinaris pointed