Pagebreaks of the print version

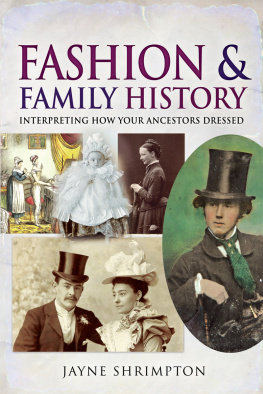

Fashion and Family History

Fashion and Family History

Interpreting How Your Ancestors Dressed

Jayne Shrimpton

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

Pen & Sword Family History

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Jayne Shrimpton 2020

ISBN 978 1 52676 026 5

eISBN 978 1 52676 027 2

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52676 028 9

The right of Jayne Shrimpton to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Acknowledgements

T his book is for everyone and since it represents over thirty years professional experience, many people have contributed content in different ways. I am especially grateful to friends and contacts who have permitted me to include images and heirlooms from their own collections. I should also like to thank Amy Jordan at Pen & Sword Books, for her endless patience and professional support.

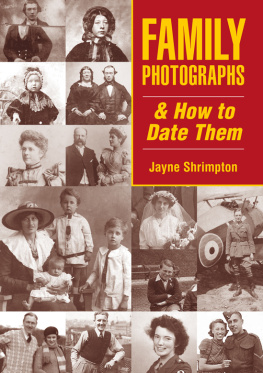

Picture Credits

Ron Cosens/www.cartedevisite.co.uk: 20, 5253, 78, 80; colour plates 6, 910

James Morley: 34, 14, 43, 70, 73; colour plates 5(a) & (b)

Simon Martin: 13, 22, 24, 31, 69, 72, 91; colour plate 4

Katharine Williams: 910, 28, 33, 38, 58, 64, 67

Remaining images are from the authors collection or are in the public domain

Introduction

F ashion might seem a frivolous subject, yet studying dress is relevant to family history in many ways. Generally speaking, knowing what people looked like in a given period what clothes and hairstyles they wore, for example, in the Regency era or during the 1890s helps with envisaging life in those times. As an art, dress and photographic historian, my belief in the value of accurate pictorial material underpins the strong visual emphasis to this book. Part of its aim is to provide informative and inspirational contextual illustrations in the form of historical prints, paintings, photographs and advertisements; often absent from documentary-based genealogical research, these images bring us literally face to face with our past.

This study focuses on dress in Britain from 1800 until 1950 a critical period spanning the so-called Industrial Revolution that transformed the nation from a traditional agrarian society to an urban, industrial society and the aftermath of the Second World War. This timeframe encompasses our families relatively recent histories, beginning with ancestors born around six to eight generations ago and ending around the time that we, or our parents, were born. Rich source material reveals how fashion and dress accelerated throughout those 150 years, responding to a changing economy and society, reflecting evolving tastes and needs, new intellectual ideas and advancing technology, and the rise of modern popular culture.

Many people living during the nineteenth and early/mid-twentieth centuries would have been far removed from the luxury high-end modes emanating from Paris (the source of western style); yet looking back, we observe how major sartorial trends representing progress for example, the adoption of female trousers do gradually gain in popularity and become widely established. It is also evident that the fashions prevailing at any given time influence the form and development of all types of clothes, even uniforms and the purposefully anti-fashion garments that minority groups adopt. Fashion is an inescapable aspect of human existence.

Exploring our ancestors relationship with dress helps us to understand their daily lives more clearly than many other avenues of historical investigation. Dressing in the morning, attending to personal grooming, selecting work or leisure wear, shopping for clothes, painstakingly sewing or knitting garments, dressing up for special occasions, packing for holidays, being photographed in favourite outfits or budgeting to clothe a large family; these intimate, intensely human routines and rituals, joys and challenges represent time-honoured experiences, connecting the generations in familiar ways.

Everyone has to wear clothes for basic modesty, protection, warmth and comfort, but throughout history dress has also served to demonstrate a persons age, gender, social status, occupation and place in the world, signifying who they are or perhaps how they want to appear. Work wear has featured prominently for most people, with standardised outfits or official uniforms characterising some occupations. Throughout time it has also been considered important to present a respectable public appearance, although some have struggled, through poverty, to maintain a decent wardrobe.

Over time, particular forms of dress have symbolised important individual, family and community rituals, reflecting recognised rites of passage and certain occasions: some special clothing customs have survived to the present day, such as bridalwear, while others, like prescribed mourning attire, represent obsolete traditions. Conversely, other types of outfit evolved almost beyond recognition throughout our period, particularly holiday and sports wear relaxed, easy-fitting clothes offering respite from the strictures of formal fashion.

Examining dress, its acquisition and preservation reveals much about our predecessors economic circumstances, their shopping habits and skills with needle or machine. Compared with todays easy access to fashion and ready-made disposable goods, clothing played a heightened role in the past, when every dress item was a carefully considered purchase, its price, quality, durability and overall value weighed up in relation to its intended purpose. Lengths of cloth for making up into garments, complete clothes, their trimmings and accessories all had an intrinsic worth: they were precious commodities, valuable personal property. The clothing of the poor usually comprised the majority of their material possessions; a form of portable wealth, jewellery, garments and accessories were readily exchanged for money. In most families, clothes and footwear were expected to last and were looked after until they could no longer be worn.

Earlier generations understood different textiles and their properties, what fabric best suited different garments and how clothes and accessories must be washed, ironed, stored and renovated. Traditionally most females learned to sew, and until the second-half of the twentieth century the women of the house often stitched or knitted some of the familys clothes. Women (and some men) diligently altered, refurbished and mended dress items and had boots and shoes regularly repaired. The further back in time we travel, the more complex and time-consuming was assembling and maintaining a wardrobe.