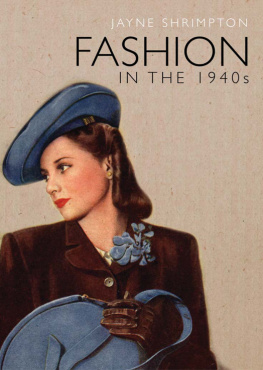

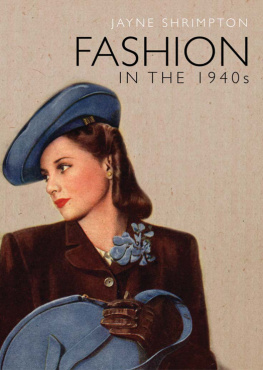

FASHION IN THE 1940s

Jayne Shrimpton

Garments produced under the governments Utility scheme were economical, yet many designer models for suits, coats and dresses were extremely smart and stylish.

Floral dresses, knitwear, checked sports jackets and patterned ties were all late-1940s fashion features, as seen in this studio photograph from 1947.

CONTENTS

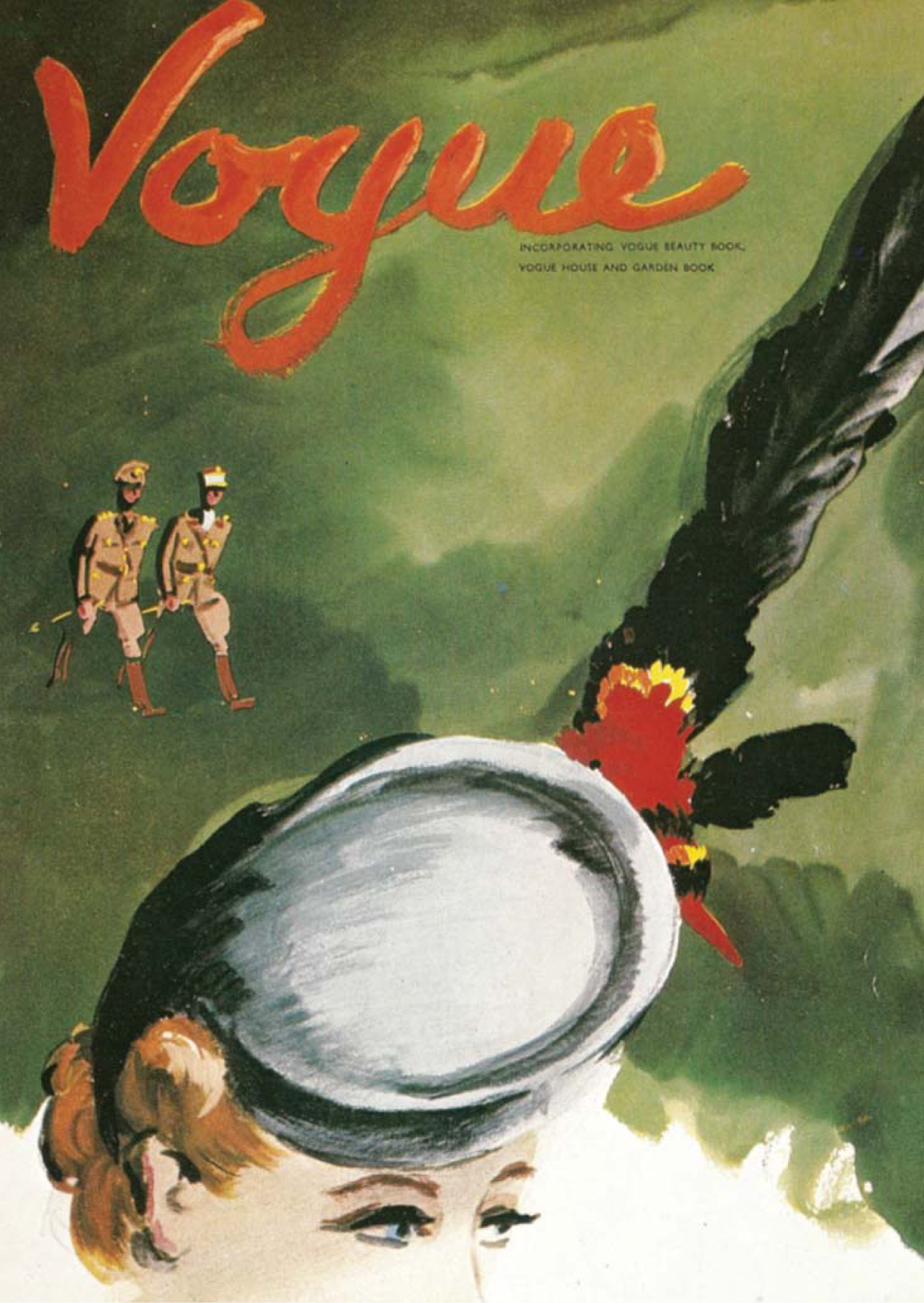

Parisian fashions are defiantly displayed on this Vogue magazine cover from March 1940, shortly before the fall of France.

INTRODUCTION

F ASHION DURING THE 1940s was dominated by the Second World War. Britain was fortunate compared with some countries at war, being neither occupied by enemy forces nor experiencing significant fighting on home soil, but the march of global events and the tremendous effort needed to support her participation in the conflict between September 1939 and May 1945 transformed everyday civilian life: never before had the home front been so completely involved in a war. By 1941 the entire populace had been mobilised in a common cause that of conserving precious resources and ensuring their allocation to the industries where they were most urgently needed. Stopping just short of nationalisation, the British government controlled textile and garment production with regimental precision, decreed what should and could not be worn and attempted to influence the nations whole perception of fashion, not only during the war but in the years of shortages, debt and inflation that followed. Winning battles over fashion, while maintaining morale, was essential to the greater war effort and would afterwards aid the nations economic recovery.

At the dawn of the new decade Paris was the acknowledged leader of fashion, but following the German occupation of France in June 1940 French industry was redirected towards the needs of the Third Reich. Some Parisian fashion houses continued to operate but they no longer served an international clientele and for the remainder of the war French haute couture became strangely insular, evolving along extravagant lines that diverged from dress elsewhere. Meanwhile, in Britain the traditional concept of fashion, with its implied freedom of choice and expression of personal taste, was being challenged. After the Blitz began in August 1940, there was little time for fashion: opportunities for leisure activities and dressing up were few and there was less to wear as material shortages escalated. Whether an individuals garments were made to measure by professional tailors and court dressmakers or bought from upmarket London shops, local outfitters, popular chain stores or market stalls, they became less formal and more functional, shaped by the exigencies of war.

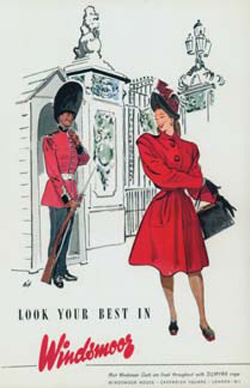

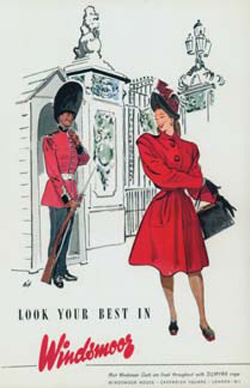

Military uniforms strongly influenced womens fashions, as demonstrated in this 1946 advertisement by British clothing company Windsmoor.

London design talent was harnessed by the government to help create economical styles. Military uniforms strongly influenced female dress as the sharp, tailored silhouette of the late 1930s developed into classic 1940s civilian fashions, a disciplined style that was trim and smart.

Suits featured a narrow or modest A-line knee-length skirt and a fitted jacket with padded shoulders and nippedin waist; coats and daytime dresses followed similar lines. Hats also evolved a martial air: for example, when Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II) joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS), her peaked cap inspired a fashion for cap-shaped hats, while her adoption of a simple scarf tied under the chin awarded the practical wartime headwear the royal seal of approval. As Princess Elizabeth (born in 1926) and Princess Margaret (born in 1930) reached their formative years they engaged increasingly with 1940s style trends, observed by an admiring public.

King George VI and his family maintained a highly visible profile during the war, declining to move out of London and sharing in the citys experience of air raids and bomb shelters, presenting an exemplary image to the nation. Queen Elizabeth radiated confidence and grace, kindness and strength, her personal sense of style reflecting traditional upper-class English taste with its subtle hint of eccentricity. The royal couturier was Norman Hartnell, whose claim to be more than partial to the jolly glitter of sequins and love of the theatre made him the perfect designer to dress the Queen. Working together, the Queen and Hartnell created a refined and stately public image through the use of soft materials, subtle colours, fur stoles and fine accessories, her most recognisable trademark being a string of pearls. When visiting areas of London devastated by bomb damage, it was decided that she would not wear morbid black costumes; instead, inspired by the semi-mourning colour lilac, she chose muted pastel shades, suggestive of hope. She was always immaculately attired on these occasions, to show respect for those members of the public who had dressed up to see her. Nonetheless, she followed wartime clothing restrictions, her clothes sometimes being cut down for her daughters and older outfits re-modelled.

The Queen maintained a dignified appearance throughout the war, while the royal princesses kept abreast of fashion. This photograph was taken on Princess Elizabeths eighteenth birthday in April 1944.

Most men in the services had few occasions to adopt civilian dress during the war. This airman wore a loose 1930s-style three-piece lounge suit for the going-away photographs following his wedding.

Girls dress resembled female adult styles during the 1940s, although white ankle socks were worn in place of stockings.

In general British male fashion remained conservative for much of the 1940s. Relatively few new suits were made during the war, as millions of men were in the services and wore a uniform: when occasion required a civilian suit, many made do with their existing two- or three-piece lounge or business suit, with its loose pre-war silhouette. Conventional men wore a hat outdoors the city bowler, a semi-casual felt trilby or the working mans cloth cap.

Childrens wear also presented a relatively standardised juvenile version of adult dress throughout the 1940s, while a regulation uniform was obligatory for most school pupils. For leisurewear, hand-knitted jerseys, sweaters, cardigans and outdoor hats, gloves and mufflers were popular for men, women and children. Many women were accustomed to making and repairing at least some of the familys garments long before home sewing and mending became a wartime necessity.