BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA

This electronic edition published in 2019 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2019

Copyright the Authors 2019 for their individual texts

Copyright The Museum at FIT 2019 for this edition and its images

Valerie Steele has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Editor of this work.

For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page.

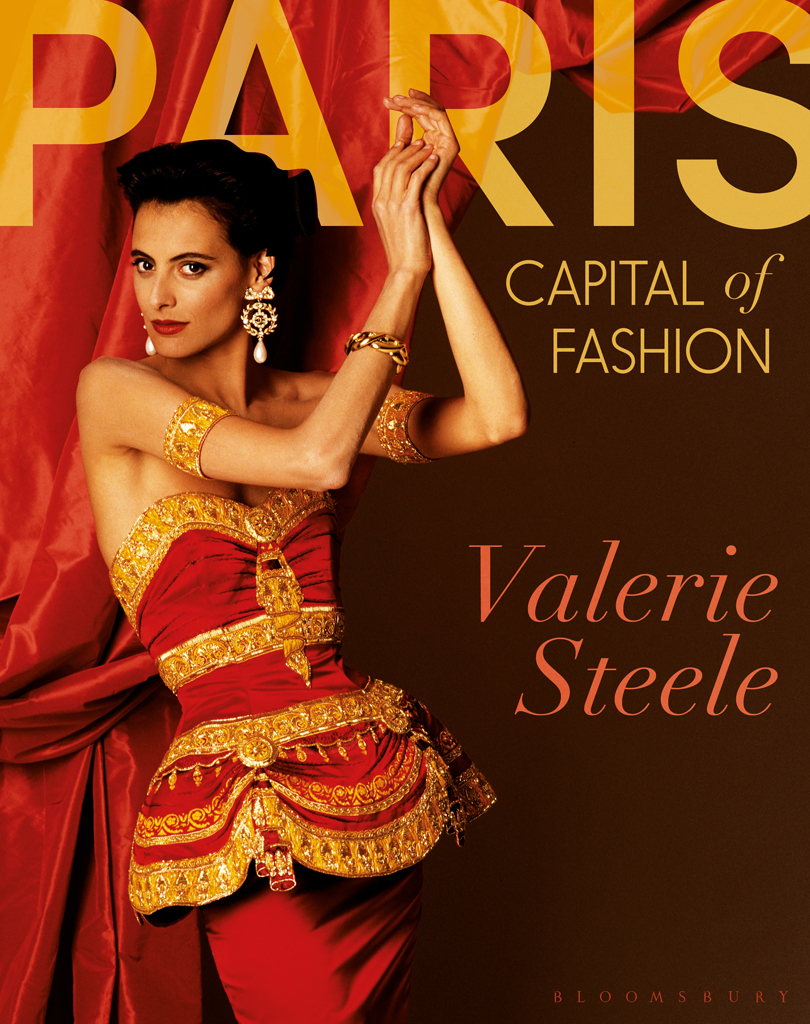

Cover design by Adriana Brioso

Cover image by Karl Lagerfeld CHANEL

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes.

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-3501-0294-1 (HB)

ISBN: 978-1-3501-0295-8 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-3501-0296-5 (ePDF)

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletter.

Contents

Preface

The history of Paris fashion blurs inextricably into myth and legend. Most commonly, it is presented as a genealogy of genius, focusing on the great Paris designers, kings or dictators of fashion, from Charles Frederick Worth, founder of Parisian haute couture, to Paul Poiret, Gabrielle Coco Chanel, Christian Dior, and beyond. These are, indeed, timely subjectsand they are not neglected here.

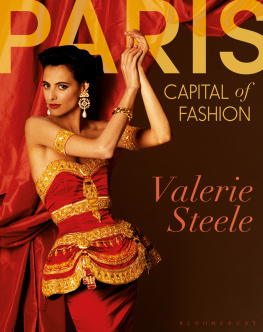

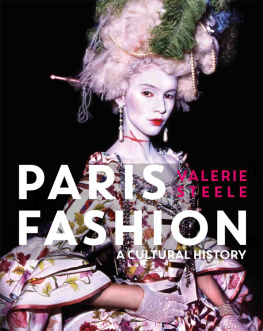

Paris, Capital of Fashion will certainly feature masterpieces of the haute couture. Yet both this book and the exhibition that it accompanies deliberately go beyond the popular subject of the Parisian couture. Like my book, Paris Fashion: A Cultural History, this volume explores the cultural construction of Paris fashion and Paris as the capital of fashion. However, it does so by explicitly placing Paris fashion within a broader, global narrative. Several essays compare Paris with other fashion cities and within the world order of fashion capitals. Other essays drill down into key aspects of the mythology of Paris fashion, interrogating concepts such as fashion capital, the Parisienne, and Parisian couture. Looking at the subject from a variety of different angles, my co-authors and I explore how the idea of Paris fashion works across fashion cultures.

By tracing the phrase capitale de la mode, I discovered a new way to explore the history of Paris and its evolving significance in the cultural imaginary. The splendor of the court at Versailles undoubtedly contributed to the establishment of French fashion leadershipand has its corollary in the spectacle of the haute couture today. But the stereotype of Paris as having been the capital of fashion ever since the reign of Louis XIV was a foundational myth constructed in the middle of the nineteenth century. Similarly, the equation of Paris with the Parisienne was a result of the feminization of Paris fashion in the age of high capitalism, as London became the capital of menswear and the real capital of the nineteenth century.

In addition to its reputation as the capital of feminine fashion, Paris has also been identified as the capital of art, revolution, and modernity. When Charles Frederick Worth transformed the couture from a small-scale craft into big business, the term initially used was grande couture, referring to the large size of an establishment, and distinguishing it from petite and moyenne couture. The term was only changed to haute couture (high sewing) when this part of the Paris fashion system was threatened by the growth of mass-produced clothing; hence, the necessity to emphasize the coutures elevated status, its artistry, luxury, and good taste.

The geographies of fashion and especially the concept of the fashion city have attracted increasing attention among scholars and city planners alike. Christopher Breward, author of Fashioning London, has recently collaborated on a major study of fashion in Shanghai. His essay, Paris, London, Shanghai: Touring the Fashion Imaginary, utilizes tourist guidebooks from the 1920s and 1930s to explore the process of stereotyping for three modern fashion cities: fashionable expat Paris, elite, masculine [London]... the Anglo-Saxon dark mirror of Paris, and Shanghai, the Paris of the East!... the New York of the West!... the most cosmopolitan city in the world.

David Gilbert, co-editor with Breward of Fashions World Cities, places the rise of Paris within the context of national rivalries. In his essay, Paris, New York, London, Milan... Paris and a World Order of Fashion Capitals, he focuses on the four most important fashion capitals of today, while also providing an historical perspective. It is not accidental, he suggests, that the Paris couture system was aggressively promoted after a humiliating military defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 18701871. He also provides a new and more nuanced picture of the relationship between Paris and New York in the aftermath of the Second World War, when the strongest theme is the active, creative, and commercial use of the idea of Paris in New York.

Perhaps most importantly, Gilbert demonstrates how Paris fashion works through the connections and flows of material objects and people. For example, it supports a sense of group identity among non-French elites who wear Paris fashion. It also works through imitation, as when New York manufacturers profit by copying Paris fashions. Alternatively, Paris fashion can be something that other fashion cultures could be defined againstas when Paris is stereotyped as dressy and New York as sporty. As for the status of fashion capitals today, Gilbert suggests that since reputation trumps the design and production of actual garments, Paris remains in first place.

Grazia dAnnunzios essay, Paris and a Tale of Italian Cities, demonstrates how long it took for Milan to become Italys fashion capital, let alone one of fashions world cities. With Italian unification in 1861, Turin became both the national capital and Italys first modern fashion city, but it was soon supplanted by Rome, which subsequently battled with Florence, Venice, and even Capri, before ceding leadership to Milan. Although the Fascist dictatorship (19221945) established policies against French fashion, Italian designers remained covertly dependent on Paris. As dAnnunzio points out, Mussolinis daughter wore a wedding dress by the Roman couture house Montorsi, which was unanimously praised as truly Italian. Such a pity that it was based on a Chanel pattern!