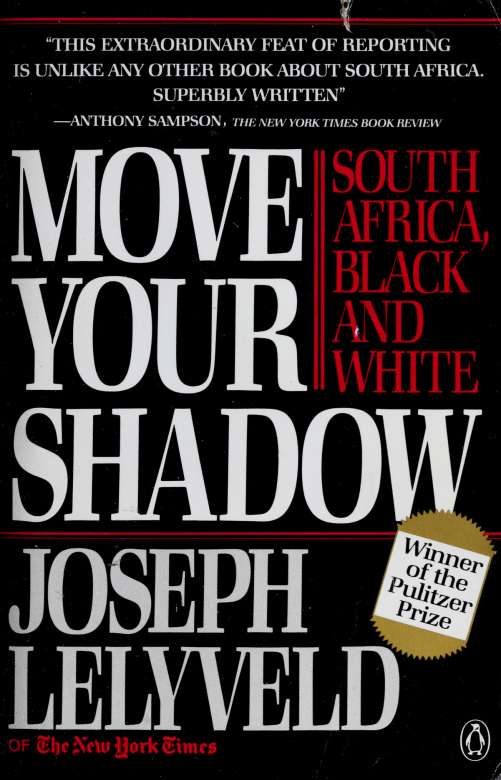

Joseph Lelyveld - Move Your Shadow South Africa, Black and White

Here you can read online Joseph Lelyveld - Move Your Shadow South Africa, Black and White full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1986, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Move Your Shadow South Africa, Black and White

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:1986

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Move Your Shadow South Africa, Black and White: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Move Your Shadow South Africa, Black and White" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Move Your Shadow South Africa, Black and White — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Move Your Shadow South Africa, Black and White" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

Wena azi lo golof? Mina hayifuna lo mampara mfan.

Have you caddied before? I don't want a useless boy. Tata lo saka gamina.

Take my bag of clubs. Tata mabol, yena doti. Susa yena nga lo manzi.

These balls are dirty. Clean them with water. Muhle wena tula loskati lo-mlungu ena beta lo bol

You must be quiet when my partner plays a shot. Tula!

Be quiet.

Noko wena lahlega lo futi bol, hayikona mail

If you lose another ball, there will be no tip for you.

Susa lo-mtunzi gawena. Hayikona shukumisa lo saka. Move your shadow. Don't rattle the bag.

J. D. Bold, Fanagalo Phrase Book, Grammar and Dictionary, the Lingua Franca of Southern Africa, 10th edition, 1977

/ can tell you the things that happened as I saw them, and what the rest were about only Africa knows.

Herman Charles Bosman, Mafeking Road

CHAPTER 1

Out-Kicked

hen they are out to demonstrate their decency and goodwill, to themselves as well as others, white South Africa's racial theorists are inclined to lose themselves in a riot of euphemisms, analogies, and fatuous forecasts. A lot of words get spilled as the urge to be understood clashes with an aversion to being understood too well. But when being understood is no longer an issue, language can be used sparingly. The letter informing me I had a week to clear out of South Africa was a model of economy, unencumbered by explanations. 'Tou are hereby instructed," it said, *'to make arrangements for yourself and your family to leave the Country on or before the 28th April, 1966."

We had been there for only eleven months, but the message had long been expected, ever since an official had canceled a lunch in Pretoria, privately explaining that he would be compromised if he were seen again with someone the Cabinet had decided to expel. When the snub was finally made official, my immediate reaction was relief. A weight had been lifted, and as we walked out of the terminal at Jan Smuts Airport to our plane for Rometwo days ahead of the official deadlineI had^ feeling of lightness, of freedom as a palpable sensation, such as I had never known before. Possibly it occurred to me at that moment to wonder whether I would ever set foot in South Africa again. But since I had now been officially certified an enemy"one of South Africa's most notorious enemies in the world," an Afrikaans-language newspaper would later say, honoring me beyond my deserts that would have been tantamount to wondering whether the regime would crumble and fall in my lifetime.

Fourteen years later, when the suspicion that I might be reconstituted as a persona grata in South Africa hatched itself almost in

4 MOVB YOUR SHADOW

stantly into a compulsion to return, I dould remember the sense of relief and lightness I felt bn leaving as vividly as I could recall anything about the place. It was a memory I willed upon myself almost daily to check my headlong flight from Manhattan, where I thought I really belonged, and another uprooting of my family. The white regime hadn't crumbled, and even with the transformation of Rhodesia into black-ruled Zimbabwe, then taking place on its northern frontier, it wasn't about to do so. But the whites' old urge to be understood, coupled with their need to believe their own propaganda about how much had changed, gave me a slight opening; at least that was my calculation. My work as an editor in New York occasionally brought me into contact with South African diplomats who seldom failed to say the diplomatic thing: that my expulsion had been an aberration, or that those had been the bad old days, or that I would be astonished by the changes. Getting carried away, they sometimes seemed even eager to make me a witness. What may have been intended as no more than a civilityor, at most, a suggestion for a brief visitI took as a sporting wager, even a dare.

I had long had a weakness, amounting to a craving, for going back, not only to South Africa but practically anywhere I had worked as a reporter. There was something irresistible about returning to a story you had once covered; it was like a trip in a time machine, one of the few ways a newspaperman could inject a little coherence and resonance into a vagabond life. To give only one example, a few years before I started to be obsessed again with South Africa, I had gone back to Philadelphia, Mississippi, where three young civil rights workers were murdered in the ''freedom summer" of 1964. I had been to Philadelphia only a matter of weeks before I left the first time for Africa. It was the opportune moment when the conspiracy to make an example of James Chancy, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner was just cracking open. On my return I sat one evening with a white man named Cecil Price. An intimidating deputy sheriff in 1964, when he advised me one afternoon to get out of town, he had eventually spent four years in a federal penitentiary for the central role he had played in the conspiracy. Now, a member in good standing of the golf club, he was only too happy to talk about Cecil junior's experiences with black teachers ip an integrated school or his own impressions of the black experience in America as related in the TV series Roots, which he rated as only **fair" because, he said, ''the violence part was played up a bit too much."

OUT-KICKED 5

Going back to Philadelphia, Mississippi, for a few days was one thing; going back to Johannesburg for a few years, something else. But as I rummaged through fading memories, I knew as a certainty that no story I had ever covered, no place I had ever been had gripped me as wholly and intensely as South Africa. Remembering in the gray days of a Manhattan winter the scale of the land and its antagonisms, and the vividness of personality that came with them, I felt a pull that was other than nostalgia.

I didn't need to remind myself that there had been places I had enjoyed more; ''enjoyment" was definitely not a word I associated with South Africa then. It was a time of silence and fear, when the system of racial dominance known as apartheid was being elaborated as an ideology and the security apparatus, having outlawed and crushed the main black nationalist movements, was stamping out the few sparks of resistance that white radicals had managed to ignite. To a newcomer the supporters of the government seemed a monolith; its enemies, a subdued, if not cringing, mass. The first South African to be executed in the apartheid era for an act of political violence, a white romantic named John Harris who had foolishly imagined he could shake the regime by leaving a bomb in a railway station, had just gone to the gallows singing **We Shall Overcome." Finishing with the radicals, the security apparatus seemed to be switching its focus to slightly larger but nonetheless minuscule coteries of white liberals who still ventured to speak and act on the premise that South Africa was a multiracial country.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Move Your Shadow South Africa, Black and White»

Look at similar books to Move Your Shadow South Africa, Black and White. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Move Your Shadow South Africa, Black and White and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.