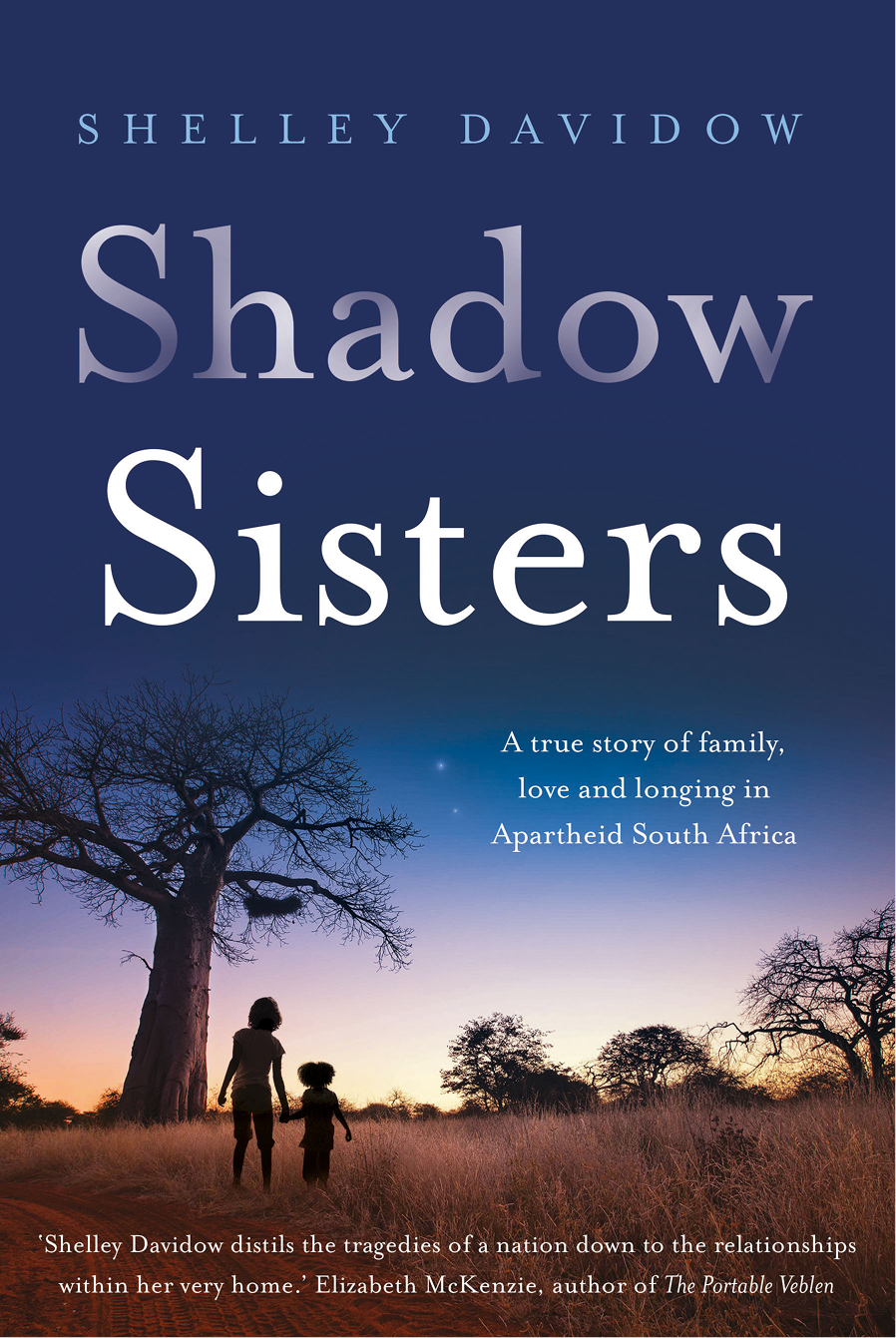

Shadow Sisters is a powerful memoir of place: a young woman coming of age in a divided nation on the verge of great upheaval. For a time they are one story, held together by the vast South African landscape. Perceptive, tender, beautifully told. Inga Simpson, author of Understory

Shadow Sisters takes us on a beautiful, heartrending, unflinching voyage to a South Africa we have seldom, if ever, seen in contemporary literature. Viewed through the lens of Davidows liberal white family both pre- and post-Apartheid, this South Africa is a beautiful and terrible place, haunted by ghosts of its past, tangled in a web of connections and disconnections that may never be unwound. Davidow sifts through memories like a mystery detective, seeking truth and, if possible, reconciliation, as she searches also for her place in the world. This is a lyrical, thought-provoking memoir, breathtaking in its honesty, one of the bravest, truest you will ever find. Molly Gloss, author of The Hearts of Horses

In this brilliant memoir of a youth spent in South Africa during the terrifying years of Apartheid, Shelley Davidow distils the tragedies of a nation down to the relationships within her very home. Its been a life indelibly marked by the violence of the era, yet lifted by the beauty of the vast continent and the enduring human spirit. This book left me stunned and somehow transformed. Elizabeth McKenzie, author of The Portable Veblen

Shelley Davidow is the award-winning author of over 40 books. She writes across genres, for adults, teenagers and children. Her recent non-fiction titles include Whisperings in the Blood , Playing with Words , and Fail Brilliantly . She is a lecturer in the School of Education at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Queensland, Australia, and lives near the beach with her family.

Shelley Davidow is the award-winning author of over 40 books. She writes across genres, for adults, teenagers and children. Her recent non-fiction titles include Whisperings in the Blood , Playing with Words , and Fail Brilliantly . She is a lecturer in the School of Education at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Queensland, Australia, and lives near the beach with her family.

www.shelleydavidow.com

Bookclub notes for Shadow Sisters are available at

www.uqp.com.au

To my family

A House by the River

T he night Leena arrived, rain blanketed Johannesburg. The river, just a hundred metres from our house, roared in flood.

I closed all my bedroom windows, even the two small ones. Thieves and murderers loved storms. A loud crash of thunder could mask breaking glass. Distant rumbles could hide the sound of a crowbar forcing open a security gate at the properties of those rich enough to have one. Besides, open windows at night were simply an invitation for someone less fortunate than you to stick a long pole with a sharp end through the gap and hook things out of your room: your blanket, your pillow, your new watch (a present for your eleventh birthday from your dad). You had to think of these things.

A short while later, my brother Larry and I sat at the dining table with our mother and stepfather, our two younger half-brothers already asleep.

The knock at the door made us jump. Larry looked at me. I looked at our stepfather. Who would be outside at this time of night, in this weather?

I moved closer to Larry. Our parents had separated just after I turned four. Larry was a baby. Perhaps thats when fear took hold. Or maybe it started the night the heater caught fire next to Larrys cot and I woke to the smell of burning asbestos and ran screaming into my mother and stepfathers room. Or maybe fear just lived in the countrys air, inscribed into the molecules we inhaled every single day. I slid to the floor behind the table.

My stepfather stood against the front door. Who is it?

Images of robbers with panga knives, of men with guns and cold hearts coming to kill us, tumbled through my mind. Though we had nothing, any stuff was worth taking to those who had less than nothing.

Its me, Leena. Can you open the door?

I came out from hiding. A gust of rain-sodden wind blew through the house and she stood in the entrance hall, wearing a black plastic bag with holes cut into it for a raincoat. Puddles of water collected around her on the parquet flooring.

Thank you. Leena wiped her face with a puffy hand. Her eyes shimmered as she glanced from me to my mother.

Shelley, go get a towel, please, my mother said. Lee, you must be freezing. Come and sit down. Whats going on? Are you okay?

No, madam.

Lee, please. Use our first names. Whats happened?

I ran to the bathroom and ripped a big blue towel off the rack. When I came back into the dining room, Leena was sitting at the table between my mother and stepfather. I placed the towel around her shoulders, but she took no notice.

I promised the old mister and missus, she said, looking at my stepfather, that I would always look after your family. Im here to look after you.

My mother glanced at my stepfather. Silence.

Decades ago, Leena worked as the domestic servant for my stepdads parents. As nanny, she took care of my stepdad and his brothers. She cooked and cleaned and made the boys sandwiches for school. She gave them kindness and comfort and they loved her, especially my stepdad. She lived out the back of the family home in a narrow garret with a high window. No plaster on the walls, just raw brick. A bare concrete floor. Her bed legs on bricks to keep her safe from the Tokoloshe the evil spirit who crept into beds and wreaked havoc on lives.

Leena had been working for the family since she was nineteen or twenty. Later, when she had her babies, she went home to Hamanskraal, a hundred kilometres from Johannesburg the middle of nowhere. Solomon and Brenda, Leenas two children, grew up in the echo of their mother always going. She left their upbringing to her mother, and got to see them twice a year. Each time she went home, she stayed for three weeks. She made sure that the children went to school, that they had medicines for when they got sick. That was what the money was for. Life as a domestic servant in the all-white suburbs of Johannesburg under Apartheid allowed Leenas children and her mother to eat and have a roof over their heads.

Leena pulled off her plastic-bag raincoat. She came to look after us, she said, only we werent the ones who needed looking after.

I have left my job as domestic servant for the Pienaar family. I have to go up and down the stairs and work hard six days a week. My blood pressure is dangerous. Sometimes I think I will die. I must work Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday and every Sunday. Get up at six and sometimes dont leave the job until ten at night. Where can I go? You see? Where can I go?

I breathed in the smells of starched servant uniform and sweat and rain.

You can stay with us until you get better, my mother said. Just rest here, recover your strength.

Of course, said my stepfather. Lee, you always have a home with us.

We occupied every room, though our growing family.

Lee, you can stay in my room, I said.

She dried her eyes with the wet apron that matched the rest of her yellow uniform. South African maids all wore uniforms: a matronly, collared dress; a doek (a scarf tied like a napkin around the head) and an apron.

Thanks, Thandiwe , Leena said. My name from that moment on, meaning loving one. You are a kind little girl.

And so in 1981, Leena came to us, homeless, without a cent to her name, an illegal resident in the land of her birth.

~

We lived on the outskirts of the white suburb of Rivonia, in an old clubhouse on a former estate called Glenwilliam. Once white-washed and stately, the buildings brown painted doors now flaked around the edges, revealing rotting wood; the rusty windows squeaked when they opened; the high ceiling turned mouldy where it met the wall. Our living room, dining room, workspace and play area each occupied a section in a giant ballroom that once belonged to a community of rich white folks of a bygone era whod danced and listened to concerts here. At the front, the wide veranda with slate floors gave us a giant undercover run-around area when summer thunderstorms rolled in from the south.

Shelley Davidow is the award-winning author of over 40 books. She writes across genres, for adults, teenagers and children. Her recent non-fiction titles include Whisperings in the Blood , Playing with Words , and Fail Brilliantly . She is a lecturer in the School of Education at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Queensland, Australia, and lives near the beach with her family.

Shelley Davidow is the award-winning author of over 40 books. She writes across genres, for adults, teenagers and children. Her recent non-fiction titles include Whisperings in the Blood , Playing with Words , and Fail Brilliantly . She is a lecturer in the School of Education at the University of the Sunshine Coast in Queensland, Australia, and lives near the beach with her family.