Table of Contents

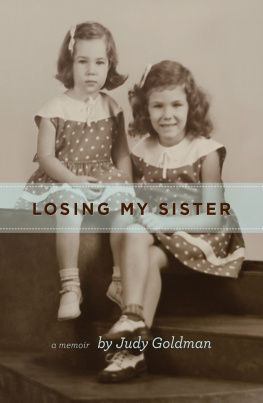

For My Family, Before and After.

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Gabriella Burman, Elizabeth Dulemba, Jilly Dybka, Erika Goldman, Rachel Hanson, Beth Lilly, Tom Lombardo, Sherry McHenry, Sandra Novack, and Dr. Gabriel Zatlin for their valuable comments on early drafts. Thank you to the wonderful directors and faculty of Queens University of Charlottes MFA program for cultivating such an inspiring environment for writers. So much gratitude goes to my agent, Sorche Fairbank, for her powers of perception and her unfailing belief in my work, and to the talented editor Morgen Van Vorst, for getting to the heart of it, time after time. Thank you to my friends at PublicAffairs, who believe in what matters.

This book never would have happened without my mother, Miriam Handler, who gave tangibles and intangibles in her willingness to go spelunking, and to Mickey, without whom I can make no journey large or small.

Prologue

Making the Dream Life

I daydream about my sisters all the time. One whispers in my ear as I write; another suggests an afternoon snack. Look, an old round Volvo, I say aloud to no one when changing lanes on the freeway. We were sentimental about those tanklike little cars. Our parents each had one when we were small, a green one for Mom, a red one for Dad. The license plate numbers even matched, different by a single digit.

When the weather is warm, I daydream about an imaginary afternoon on a late summer vacation, the three of us together. Susie and Sarah and I lie on the periphery of a body of water, a glittering blue swimming pool somewhere almost shabby, maybe a motel with microwaves and concrete patios along the Gulf Coast of Florida, or somewhere more beautifula salt-sticky beach on Cape Cod. At least one of us makes good money if we have decided to go to the Cape. Mindful of the demands on husbands and kids, we have pried one week from our separate calendars, drawing red-pencil squares around that block of days set aside for soggy towels and frayed tennis shoes that leak sand like cracked hourglasses.

Each of us has had our share of bad love affairs, dropped out of school, gone back to school. We have traveled to Europe or out West, slung hash. Gotten speeding tickets. Gotten high. We have gotten married. We have children.

Susie and Sarah and I are devoted to one another, even though we have made our homes in distant cities. Sarah might have studied art history or become a doctor. Or a writer. She was surgically exact with words. Susie, who when she was six wanted to be a nurse, may have earned her doctorate in nursing. If she teaches, her students adore her. She is tough on them, but her laugh is a happy spike in a steady current of energy.

I have not grown up to be the TV star I planned to be when I was eight, flipping my hair and practicing That Girls intoxicating smile. Illya Kuryakin, the Russian secret agent from The Man from U.N.C.L.E., did not elope with me. Instead, I am the sister grown up.

My sisters and I have created a tribe of children still unaware that their job will be to remember us. Our sons and daughters see us as moms and indistinctly as sisters; we bicker, and roll our eyes. Keeping peace, we do not speak about certain things: a borrowed car that came back with a cigarette burn in the upholstery, or an emergency loan for a college weekend still unpaid. We snort at Susies history of boyfriends, Sarahs orderly cooking, my tall tales. We worry about our parents growing old, avoid talking about what we will do when they cannot live alone.

Our dream children look like their mothers. Mine tend toward plumpness, Susies are forceful and athletic, Sarahs elegant. They shout and argue and make peace in predictable cycles. They smell like the vapor from their sunscreen: baked chemical coconut desserts.

We three lie flat on our backs on chaise longues, near enough to our offspring to stay alert to their safety. Marco! my children yell. Polo! their cousins holler back. Our husbands never materialize in this fantasy; it is just us.

We sisters drowse in the sun, happy to be side by side with next to nothing to do. As I write this, I am forty-seven, the eldest. Susie would be almost forty-six. Sarah would be forty-two.

part one

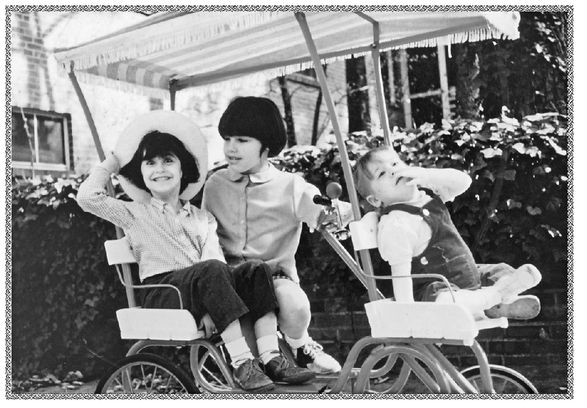

Susie, Jessica, Sarah

Sarah died... I want to stand in the middle of the room and scream and scream. I cant. I dont know how.

Journal, 1992

Are you sitting down? my mother asked across the long-distance line. We talked on the phone at least once a week, and when I heard her voice, I expected the usual: a who-can-top-this tale of her irritating boss, and a sympathetic ear to listen to the latest about my supervisor. Wedging the phone against my shoulder, I walked from the kitchen back to the bedroom, where I had been reading.

Are you sitting down are you sitting down are you sitting down. She was not askingshe was stalling for time. Her voice sounded sped up and wobbly. I knew she was fidgeting, twisting the ring with the three square diamonds on her right forefinger, then spreading her hands wide, flexing them.

I did what my mother asked. I sat down, and kept moving forward, sliding to my knees, and finally crouching on the floor, trying to be so small that the words I knew my mother was going to say would fly above my head. I felt primitive, the way a dog must feel when she hides her head under a rug during a thunderstorm. If no one could see me, I would never have to hear what was coming.

Sarah had prepared me for this day years before. We talked about her death only once, and only then because she forced me. Sarah took the role she often did, that of the big sister, while I acted like the younger woman: blithe, cheerful, and wrongheaded. After a lifetime of surgeries and lab tests, she was preparing for the possibility of a bone marrow transplant, another experiment in a succession of experiments.

Sarah had called me on a weekend afternoon. She lived near our mother outside Boston. I had moved back to Atlanta, where we had grown up.

This is going to be harder on you than it will be on me, Sarah said.

I know, I replied.

I was sulky, hating the fact that she had taken control and made me face the truth. While we talked, I imagined Sarah standing in her kitchen, looking out over Dorchesters rooftops and cutting vegetables for a snack she invented when she was a child: raw broccoli stalks dipped in olive oil and salt. Trees, we called them.

I can handle a hospital stay, I said.

Out of habit, protecting myself, I had dismissed her again. A bone marrow transplant was all this conversation was about. I imagined months in sterile isolation for her, and months for me if I passed the tests to be her donor.

Thats not what Im talking about, Sarah said. She sounded irritable and urgent. When I diethats what I mean.

I made comforting noises, demurring. You wont die from this, dont be silly, this will work, this time will save your life.

When I die, Sarah said, suddenly fierce, you will be the only one left.

Crouching on my bedroom floor, my head between my knees and the telephone receiver pushed against my right ear, my mother gave me the news I had dreaded most of my life. Sarah had died.