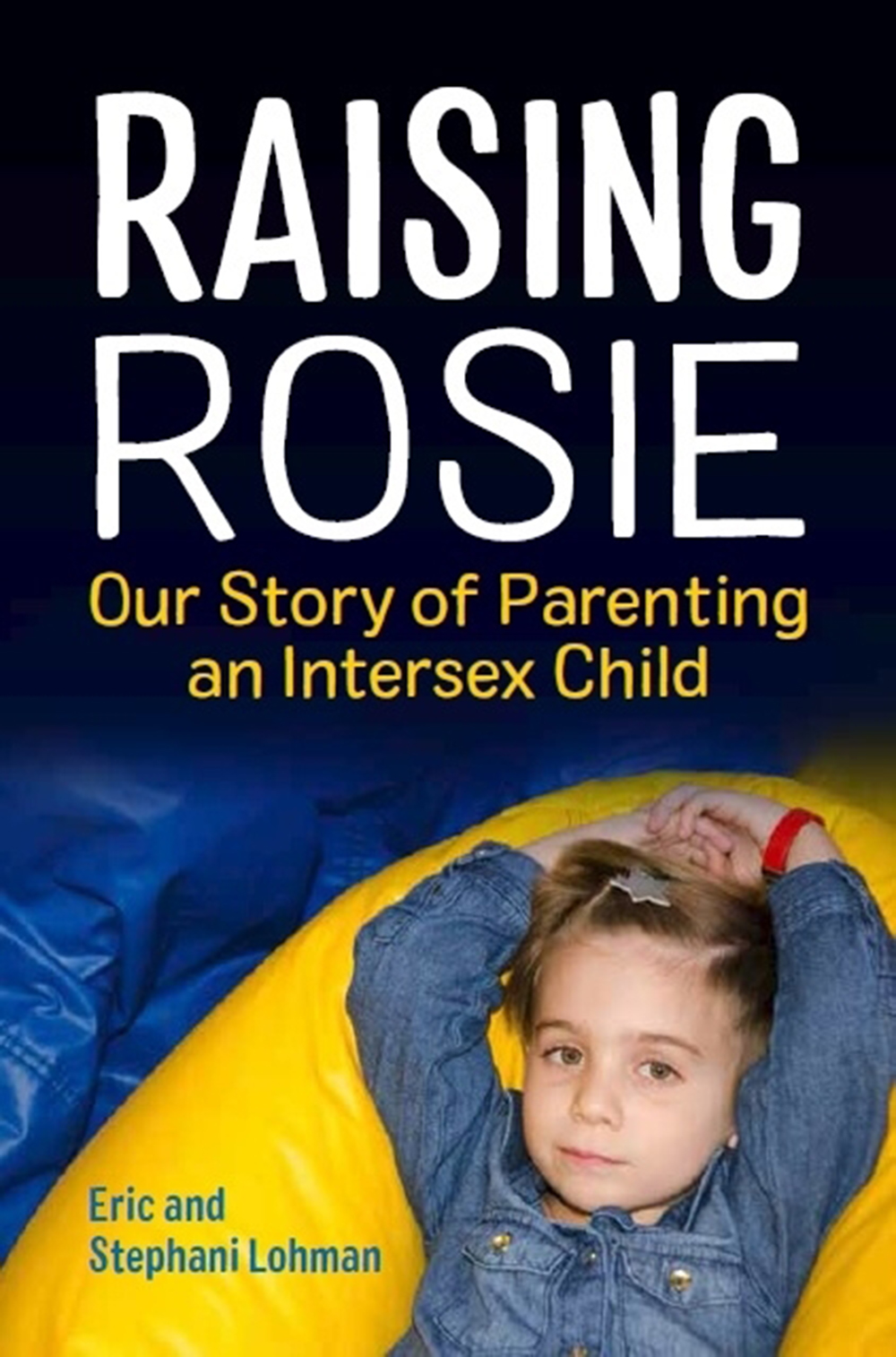

Raising Rosie

Our Story of Parenting an Intersex Child

Eric Lohman and Stephani Lohman

Foreword by Georgiann Davis

Jessica Kingsley Publishers

London and Philadelphia

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Georgiann Davis

It was in the early 1990s when an older, balding, Greek immigrant doctor with glasses as thick as his accent told my mother and me that I would never be able to have biological children. I wasnt fazed. I was thirteen years old and wanted another dog, not a baby! However, my mother, a Greek immigrant herself, was devastated. More than twenty years have passed and I can still hear her sobbing. Only now I know that the source of her uncontrollable tears was that she was privately told the truth about my body which I was not: Im intersex. The doctor made her feel horrible when he framed my body as a medical abnormality that needed to be surgically fixedfeelings that were exasperated when he instructed both of my parents to never tell me the truth about my body. With this medical advice that my parents followed, my doctor, and his colleagues, constructed a ball of shame and secrecy that my entire family would have to spend years unraveling.

I was born in October of 1980 with an external female appearance, but inside, instead of XX chromosomes, ovaries, a uterus, and fallopian tubes, I have XY chromosomes and testes; that is, I had testes before a surgeon removed them because, in his limited mindset, a girl couldnt have balls. I wouldnt learn the truth about my body until years later when I privately obtained my medical records. As I read through the redacted text that outlined my intersex diagnosis (Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome) and also communicated the doctors problematic justifications for why they felt it was best to lie to me and tell me I had ovarian cancer rather than explain that I was intersex, I felt like a freak and I was angry. While I dont agree with them, I understand that doctors were worried the development of my gender identity would be disrupted if I knew I was intersex. However, Im still shocked they thought lying to me and telling me I had cancer would somehow be better. Ive since dedicated my life to fighting for the human rights of intersex people as both an activist and a feminist medical sociologist.

Words cant quite articulate what it feels like to know Stephani and Eric Lohman, parents who have been intersex advocates from the very beginning of their intersex childs life. But, I will try. As they courageously continue to challenge medical authority, negotiate complicated privacy issues, and collaboratively join intersex activists in the fight for intersex human rights, they always center Rosietheir beautiful intersex child. If Raising Rosie is an indication of how at least some of todays parents of intersex children are navigating their childs intersex diagnosis, Im confident I might just live to see an end to the medically unnecessary and irreversible interventions designed to erase rather than embrace intersex.

Of course, the Lohmans arent raising Rosie alone. As they describe in the pages that follow, they are standing on the shoulders of many intersex activists from around the world. The global intersex rights movement was formed in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and since, it has grown in size and power. The first wave of intersex activists successfully raised intersex visibility and awareness about the horrific medical practices intersex people were routinely forced to endure without their consent. Doctors can no longer claim ignorance, as they certainly know intersex people are angry about intersex medicalization practices. Yet, doctors continue to perform so-called normalization surgeries on intersex bodies that deprive youths of their bodily autonomy. I want to make very clear that, like the Lohmans, I am not against intersex surgical interventions. Instead, I only ask that the intersex person themselves choose what, if any, medical interventions they receive. This is not an unreasonable request.

I trust Raising Rose will positively impact society, especially other parents of intersex children, in countless ways for years to come. But, with that said, I still want to publicly and preemptively reflect on the issue of Rosies privacy that may surface during your reading of Raising Rosie . What does it mean that Rosies parents have publicly shared their familys story? I read courage. I feel love. I see advocacy. And, most importantly, I accept Raising Rosie as evidence that we, people personally connected to intersex, can indeed dismantle the thin and blurry line between privacy and shame. Intersex is not shameful. It doesnt need to be hidden from the world any more than a childs birthday, school report card, winning soccer goal, or college admission decision does. I caution all of us personally connected to intersex to think about what we, consciously or not, perpetuate when we forcefully sandwich privacy and intersex in the same concern. By fixating on privacy concerns, are we unintentionally fueling the same intersex struggles we are trying to wrestle?

In my sociological research on intersex in contemporary U.S. society, I advocate that parents of intersex children need not only medical information about intersex before they consent to any irreversible medical interventions, but also, more importantly, they must receive a different kind of informationinformation that comes from being connected with the intersex community. Parents need to know they arent alone. They need to know that intersex is a natural sex variation. They need to know that their intersex child will love and be loved and that their childs intersex trait will not restrict the dreams they have for their child. Raising Rosie is an excellent resource for those wishing to engage with a different kind of information. Stephani and Eric vulnerably share their earliest concerns when Rosie was born, outline their decision-making process that led them to refuse problematic cosmetic surgeries, describe their advocacy efforts, and in the process, they offer recommendations for other parents of intersex children, medical professionals, and policy makers.

When I publicly speak about intersex, Im often asked if I harbor any disappointment or resentment towards my parents for consenting to medically unnecessary interventions on my body, while simultaneously lying to me about my intersex diagnosis. While I understand the question, it often confuses me. My parents were simply following the advice of medical professionals. They would never want to physically or emotionally harm me. As I argue throughout my scholarship, parents of intersex children are pawns in the medicalization process. They are rarely told that intersex is a natural bodily variation. Instead, intersex is often presented to them as a medical problem that should be medically corrected. In these ways, the parents of intersex children are also forced to navigate problematic intersex medicalization practices. And my parents, like the Lohmans, are no exception.

My parents have never met other parents of intersex children. And given they are both terminally ill, I do not know if they ever will. But I know they are comforted by the fact that parent advocates like the Lohmans exist so that future parents of intersex children will not have to endure what our family did.

Raising Rosie is an inspirational account of our communitys ongoing fight for intersex human rights. I hope you are as moved by it as I am.

Georgiann Davis, PhD, is an intersex scholar and activist originally from Chicago, Illinois. She joined the University of Nevada, Las Vegas Sociology Department in the fall of 2014 after spending close to ten years studying the intersection of the sociology of diagnosis and feminist theories. In her book, Contesting Intersex: The Dubious Diagnosis (2015, NYU Press), Davis explores how intersex is defined, experienced, and contested in contemporary U.S. society. She is also the board president of interACT: Advocates for Intersex Youth (2017 to present) and the former president of the AIS-DSD Support Group (2014 to 2015). You can read more about her work at www.georgianndavis.com .

Next page