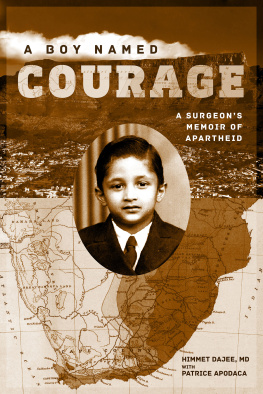

Published by Cynren Press

101 Lindenwood Drive, Suite 225

Malvern, PA 19355 USA

http://www.cynren.com/

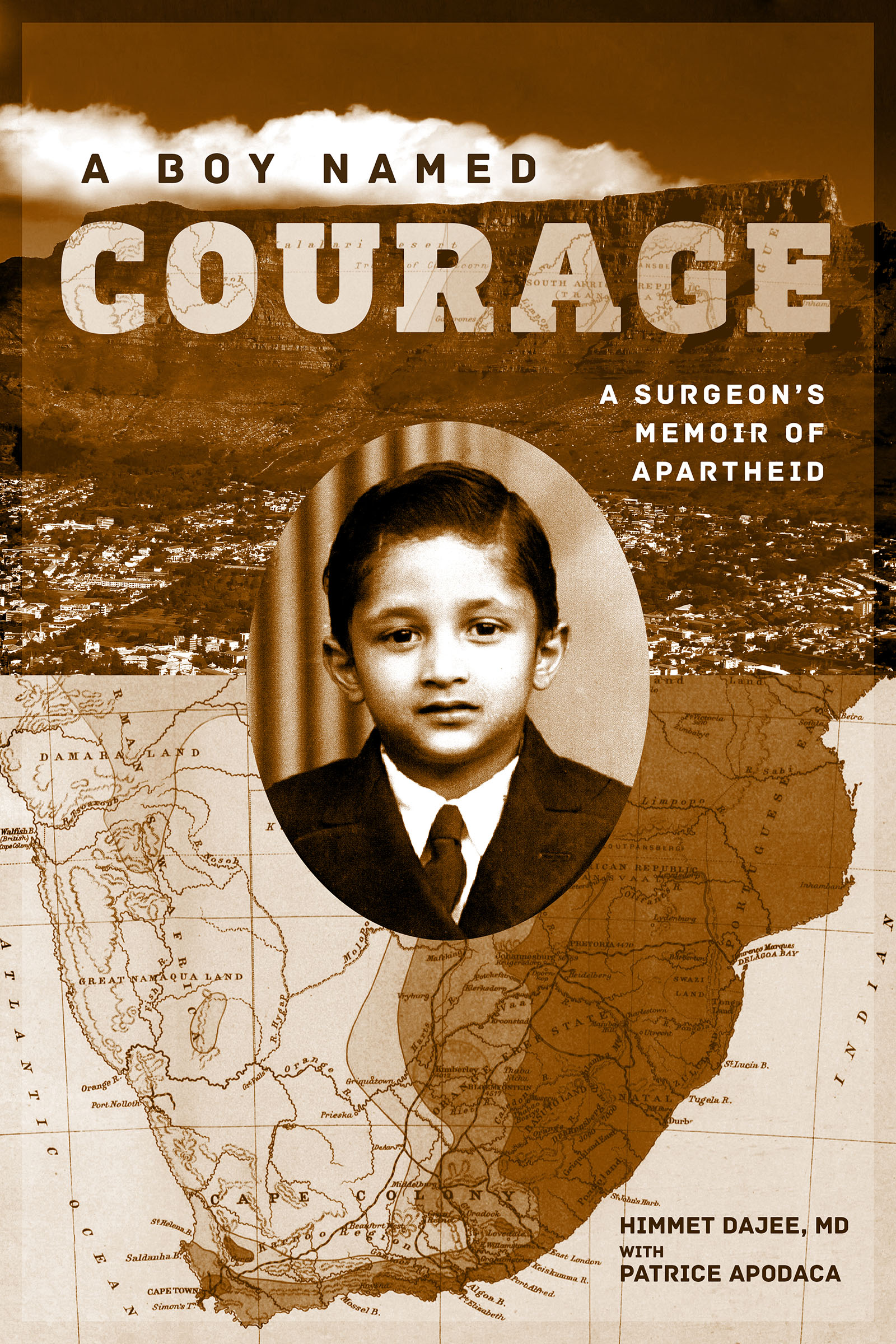

Copyright 2018 by Himmet Dajee and Patrice Apodaca

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

ISBN-13: 978-1-947976-00-9 (hbk)

ISBN-13: 978-1-947976-01-6 (pbk)

ISBN-13: 978-1-947976-02-3 (ebk)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017963485

The authors have re-created events, locales, and conversations from their memories of them. To maintain their anonymity, in some instances, names of individuals and places have been changed.

Cover design by Emma Hall

For Bhanu,

who taught me how to dream

Contents

Prologue

My home in California has a spacious balcony from which I can see, on a clear day, the shimmering Pacific Ocean in the distance, San Clemente and Santa Catalina islands nestled offshore, and miles and miles of spectacular coastline.

I bought this house many years ago, when I was at the pinnacle of my career as a surgeon. My oldest brother, Amrit, scoffed at me. Why do you want such a big house when you live alone? he demanded to know. I paid him no mind. I just wanted it and believed that at last I had earned a touch of comfort and peace from the thousands of hearts I had repaired over the years.

I had instantly fallen in love with the spiral staircase and the columnscolumns!in the grand foyer. The house had practical selling points too. It was in an ideal location just a short freeway drive away from the hospital where Id set up my practice, a critical feature for a cardiac surgeon who existed pretty much always on call. In fact, the neighborhood was so popular with doctors that it went by the somewhat dubious nickname Pill Hill.

Most of all, though, I yearned to sit on that balcony in the rare moments of solitude and introspection that a surgeons life affords. I wanted to sit there and just be.

And sometimes, while I am on my balcony gazing out toward the water, I am transported back to South Africa.

Coastal Southern California resembles my native city of Cape Town in many ways: the deliciously seductive climate, the gorgeous ocean views, the beaches lined with palm trees, and the backdrop of slate-colored mountains rimmed by desert to the north and east. Sometimes from my balcony perch, I can spot the ships lined up out at sea, bound for the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach to the north, and Im reminded of my youthful jaunts with my brothers and a few cousins or friends to Cape Towns harbor to see the ships docked there.

When I was fourteen years old, in 1956, a conflict raging thousands of miles away sent ripples to my corner of the world. In July of that year, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser seized and nationalized the Suez Canal, the main shipping route for oil tankers and merchant vessels from the Persian Gulf to Europe and America. In October, Israeli, British, and French forces pushed toward the canal. The Soviets threatened to drop nukes, and the United States issued stern warnings to all parties.

But to my adolescent mind, the Suez Crisis presented a fortuitous opportunity for adventure. Over several months, thousands of ships were diverted around the Cape of Good Hope, and many of them docked at the Port of Cape Town to refuel and pick up provisions. Locals would line up quayside to greet the visitors. My pals and I were allowed to climb the ramps and board the ships and were given tours by the sailors.

It occurs to me now that those visiting vessels offered me a rareperhaps the onlyglimpse of freedom in my young life. The sailors came from far-off lands and spoke many different languages, but even though we were strangers, they would welcome my friends and me aboard, smile at us, tell us stories, and give us coins from their home countries. They treated us not as vermin but just as they would any other rambunctious boys. It didnt seem to matter to them that we had dark skin, and that astonished me to no end.

I believe that was when I first started to plan my escape.

Cape Town is magnificent to look at, no doubt, but to me, it was like a beautiful woman with a heart of stone who crushed my spirit again and again. Those visiting ships gave me a peek into other worldsworlds where I believed I could one day leave behind the pain and daily humiliation of being a nonwhite in apartheid South Africa.

From a very young age, all I wanted was to leave my troubled homeland. As the son of Indian immigrants, I was well aware that I wasnt suffering the worst of the brutality and degradation that the Afrikaner government meted out to anyone whose skin wasnt whiteday in and day out, I witnessed the savagery unleashed on the native blacksbut what we did endure was bad enough. I knew too well the fear and injustice that were routine under apartheid, and I hated the regime with a passion that grew fiercer with each passing day.

I admit, though, that I had other reasons for wanting to leave. Not only did the apartheid policies of segregation and subjugation make me an outcast in my own country but so too did my own people in our tight-knit community: my rigid, tradition-bound father, who wanted all his children to live in lockstep with the suffocating strictures of the Indian culture, and our network of friends and relatives, who could sometimes be just as racist and exclusionary as the merciless Afrikaners.

I didnt belong in either cagenot in the tormented existence of a nonwhite living under apartheid nor in the role of an obedient Indian boy who quietly accepts his lot. I never fit in, never felt as if I could truly breathe.

I came from two worlds, and I despised them both. Only by leaving could I prove my worth and learn truly and without hesitation what I was made of. My three older brothers, each in his own way, were forging their own paths. I would learn from them and draw strength from their examples. And then I, too, would make my own way.

As I grew, that became my deepest desire, my sole focus, my cause, my reason for being. I would leave South Africa one day, and I vowed that when I did, I would never look back.

If only it had been that simple.

Nothing was ever painless in South Africaa fact that had been drilled into me for as long as I could rememberbut there was no way I could have known just how difficult the road ahead would prove to be, just how easily I could have lost the battles I felt compelled to wage, how easily I could have succumbed to grief or despair, even after I had put an ocean between myself and the rot of my native country. I like to think that it was my steely determination alone that kept me forever pushing forward, that allowed me to devote my life to saving others. But I must admit that underneath my carefully cultivated, cool exterior, I harbored a reservoir of burning rage that has fueled my journey.

I was almost shamefully ambitious. I was relentless. But above all, I was angry.

It is only now, after a long life filled with love and loss, great success and utter failure, and a consuming desire to outrun my past, that I am at last coming to understand my own heart.

1

A Boy Nam ed Courage

I wasnt expected to survive.