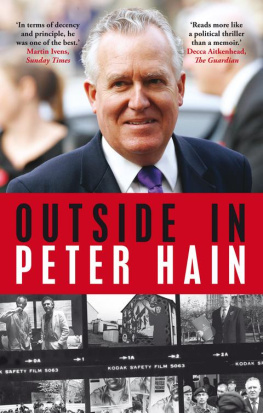

T heir first small steps later became large strides, their modest local actions led to national controversies.

Yet, when they were first asked to help, they gave no thought to where it might lead. Saying yes didnt seem at all fateful. Adelaine and Walter Hain rather stumbled, oblivious, into it all. At the time, in 1953, it just seemed the right thing to do, in keeping with their values of caring, decency, fairness and, perhaps equally important, their sense of duty.

Staying true to such values, morals, principles was important to them even if that meant sacrificing the comforts and certainties of job, lifestyle, family, friends, security and indeed country. Maintaining standards was fundamental to trying to live a life of integrity where principles mattered. They didnt try to play the hero, they didnt set out with a plan. One thing led to another and, once they had started, there was no way they felt they could walk away or let others down even though, had the consequences been known at the beginning, they mightve had cause to pause and reflect.

Ad & Wal is a story of struggle, of sacrifice, of pain but ultimately of triumph: not for themselves, but for their cause. They were survivors they came through war, penury, harassment, attacks and bitter loss, still looking on the bright side, chins up, keeping going, making the most of life, living happily at the centre of their close and growing family.

Theirs is indeed a story of their times, their era. Do their values endure? Or have they been lost in a world of personal gratification and celebrity? Could there ever be another Ad and Wal? Or are people simply not made like that anymore?

Not that they were saints everyone has flaws. I have tried to tell it as I think it was for Ad and Wal, an ordinary couple who did extraordinary things under apartheid South Africa in the 1950s and 1960s and gave up a great deal as a result. It is indeed the very fact that they were so much like their white peers and relatives that in their own words they were just an ordinary couple which makes their story intriguing, and along the way raises questions about why they did what they did, why they were rebels, when the great mass of other whites including all but one of their many close relatives did not and were not.

If you, the reader, were in their situation, would you have done what they did or stayed quietly with the vast majority, walking by on the other side?

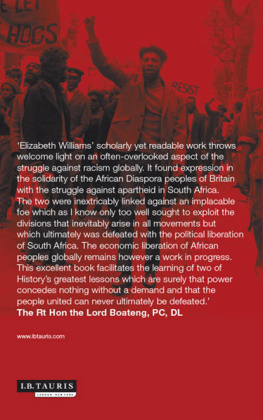

Of course being published doesnt make their story more important than those of tens of thousands of other South Africans, including whites like them, who joined the struggle against apartheid. Ad and Wal were, and very much saw themselves as, foot soldiers rather than leaders. They always insisted that others suffered a great deal more and contributed much more, and that their own role was modest.

Above all this is a story: I have aimed at readability rather than deep political or indeed psychological analysis. Other whites also brought up by anti-apartheid parents in South Africa at much the same time have written memorable books. Gillian Slovos Every Secret Thing is unsparingly, uncomfortably honest about the personal and the political underlying the leading roles in the African National Congress played by her parents, Joe Slovo and Ruth First. Lynn Carnesons Red in the Rainbow is a moving tribute to the bravery and fortitude of her South African Communist Party and ANC parents, Fred and Sarah Carneson. Eleanor Sisulus Walter and Albertina Sisulu is captivating on her inspirational in-laws. There are also insightful biographies of those times, for instance on the leaders, including Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki, where similar themes and values arise.

But writing about your parents is not straightforward and I am grateful to both for their cooperation despite their misgivings (including on my mothers side considerable emotional stress) and even embarrassment that they should be singled out. My thanks to my brother Tom and sisters Jo-anne and Sally for their own, sometimes painful, memories, and to Elizabeth Haywood for both her love and invaluable edits. My good friend and wonderful South African historian, Andre Odendaal, gave me sensitively trenchant and detailed advice without which this would have been a lesser work. I am also grateful for their help and comments to Myrtle Berman, Vanessa Brown, Jill Chisholm, Annette Cockburn, Eddie Daniels, David Evans, David Geffen, Hugh Lewin, Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke, Jo Stocks, Jill Wentzel, Ann Wolfe, David Wolfe, Duncan Woods, Jane Woods and Randolph Vigne (whose book Liberals Against Apartheid: a history of the Liberal Party of South Africa 195368 is an important source). Also to my agent Caroline Michel for her sympathetic wisdom on authorship; and to Sam Carter, Bitebacks editor, for his enthusiasm for this story. Finally to Joe Hemani for his unfailing support and generosity in friendship.

Above all to Mom and Dad Ad and Wal who will always be an inspiration to me and many, many others.

Peter Hain

Ynysygerwn,Neath

November 2013

I f the end was bitter, at the start they could not believe their good fortune.

It was morning on 21 October 1944 when two army radio operators, Walter Hain aged nineteen and Lanky Brasler aged eighteen, moved to Point 806 high on Monte Pezza in the Apennines. Among some trees they stumbled across a slittie (slit trench) wide enough to take both of them.

It was the only one like that theyd ever discovered. Normally a slittie was a one-man trench, long and deep enough to protect a soldier lying in it from shell shrapnel and flying bullets. Sometimes they had to toil away in the hard, unyielding soil to dig out a suitable slittie.

They delightedly occupied this one. To make it more secure from overhead shell bursts, they gave it a roof of tree branches topped with a layer of soil, and a gap at one end for access. As Walters meticulous diary recorded, they felt as safe as a house.

Both were soldiers of the 6th South African Armoured Division, part of the British 8th Army which, with the American 5th Army, was driving the German forces occupying Italy northwards out of the country. One of its infantry battalions was the Royal Natal Carbineers (RNC), and they were in C Company.

That morning their C Company took over a frontline position from B Company and they were able to move straight into existing slitties. Although around ten oclock German shells started coming over a hill to their left, Walter and Lanky felt very safe and were trying to sleep. But, two hours later, when shells began bursting nearby and shrapnel flying, they found the din terrifying.

The two were suddenly trapped in their safe as houses trench, the Germans pounding their lines. Then shockingly their worst fear: shrapnel tore through the access opening in the trench roof near their feet. It hit the top of Walters right thigh in the groin. I quickly put my hand down to make sure the family jewels were intact they were. Lanky shouted: Ive been hit, Ive been hit.

So have I, Walter shouted and Lanky jumped out the opening of the slittie to call for help. Then another shell arrived and Lanky grabbed his back and screamed Oh Mama, Mama, Mama.

Pandemonium. Horror. Walter pulled a moaning Lanky back into the slittie and tried to prop him up; Lanky was badly hurt very badly. The company medical orderly, Dutch, soon arrived and gave Lanky morphine; it seemed not to make any difference. Despite Walters desperate reassurances, Lanky was sure he wasnt going to make it and asked Walter to see his sister. But I told him hed be alright and the stretcher-bearers would soon be coming.