PENGUIN  CLASSICS

CLASSICS

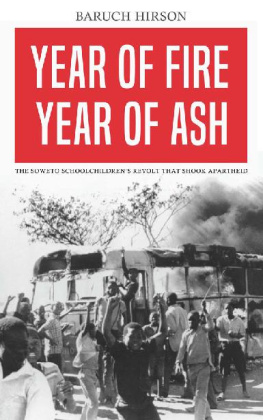

DOWN SECOND AVENUE

ES KIA MPHAHLELE was born Ezekiel Mphahlele on December 17, 1919, in Marabastad, outside of Pretoria. Raised by his paternal grandmother in the rural Northern Transvaal (now the Limpopo Province) near Pietersburg (now Polokwane), in the village of Maupaneng, Mphahlele returned to Pretoria as an adolescent, only to be called backward by teachers and his extended family. Despite these obstacles, Mphahlele excelled and earned his teachers certificate from Adams College, Natal, in 1940. He taught English and Afrikaans at Orlando High School in Soweto and, while teaching, published his first collection of short stories, Man Must Live (1947). In 1952, he was banned from teaching for campaigning against the Bantu Education proposals. Forced out of the profession, Mphahlele began working for Drum, a groundbreaking South African magazine; but soon became frustrated by the oppressive intellectual environment in South Africa and entered a brief exile in Basutolandtodays Kingdom of Lesothoin 1954. He later went to Nigeria, then France, then Kenya, then Zambia, and finally to the United States, where he stayed until 1977. While abroad, he became well-known for his anti-Apartheid activism and literature, publishing his autobiography and South African classic Down Second Avenue (1959). He would go on to write one more autobiography, Afrika My Music (1984), and three novels, The Wanderers (1971), Chirundu (1980), and Father Come Home (1984), in addition to his short stories and nonfiction. In 1978, he returned to his native South Africa and changed his name to Eskia, a reflection of his ongoing struggle with exile and identity. In 1986, the French government bestowed on him its Ordre des Palmes Acadmiques, recognizing his contribution to French language and culture. In 1998, South African president Nelson Mandela awarded him the Order of the Southern Cross. He died on October 27, 2008.

NGG WA THIONGO is an award-winning novelist, playwright, and essayist from Kenya whose works have been translated into more than thirty languages. His novels Petals of Blood; Weep Not, Child; and A Grain of Wheat appear in Penguin Classics. He lives in Irvine, California, where he is Distinguished Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Irvine.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, USA

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

For more information about the Penguin Group visit penguin.com

First published in Great Britain by Faber and Faber Limited 1959

First published in the United States of America by Anchor Books 1971

This edition with a foreword by Ngg wa Thiongo published in Penguin Books 2013

Copyright Eskia Mphahlele, 1959

Foreword copyright Ngg wa Thiongo, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this product may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Mphahlele, Eskia, 19192008.

Down Second Avenue / Eskia Mphahlele ; foreword by Ngg wa Thiongo.

pages ; cm.(Penguin classics)

ISBN 978-1-101-61679-6

1. Mphahlele, Eskia, 19192008. 2. Authors, South African20th centuryBiography.

3. South AfricaSocial life and customs. I. Title.

PR9369.3.M67Z466 2013

968.06092dc23

2013006672

To

Eva, my late Mother

Grandmother

Aunt Dora

Rebecca

... and Jenny, who bullied me

into telling her about them

Contents

Foreword

PROPHET MPHAHLELE: NAMED AFTER EZEKIEL

It was in 1963, precisely fifty years ago, that Eskia Mphahlele, then still in exile from the apartheid regime, founded the Chemchemi Creative Centre in Nairobi. Kenya was on the verge of independence, but at the time it was still a settler colony, really a mirror image of apartheid South Africa. Chemchemi is the Swahili name for a spring or a fountain. It was meant to be a place where Kenyan writers could meet and draw from the same fountain. At the time there were hardly any published Kenyan writers to speak of; my own novel, Weep Not, Child, the first in East Africa, had yet to be published. There were skeptical glances when this exile from South Africa set up this fountain in what was then seen as a literary desert. But no skepticism would deflect him from his purpose. Where others saw desert, Mphahlele saw fertile soil to plant seeds. He organized seminars for the budding and would-be writers. Mphahlele focused on the future. The young were that future.

Apart from the seminars and activities at the CCC, Mphahlele traveled widely, giving talks at several schools. The same skeptics saw him as the latter-day Don Quixote who mistook shadows for writers. Like Don Quixote, Mphahlele stayed the course, oozing optimism even when the immediate results did not seem to give cause for it. Among the schools he visited in 1963 was Kamusinga in Western Kenya, far from Nairobi. One of the students who attended the talk that day later became Dr. Henry Chakava, who has published many Kenyan and African writers, including the Kiswahili translations of nearly all the African writers of the continent, the fulfillment of a dream of a lone prophet, an exile, from South Africa.

This prophet was not just a dreamer but a battle-tested activist and organizer. I first met Mphahlele in Kampala, Uganda, during the 1962 Conference of African Writers of English Expression. We knew him as Ezekiel Mphahlele. The conference brought together for the first time writers from South, West, and East Africa, as well as the Caribbean and America, the greatest pan-African gathering of the time, in some ways surpassing the previous black writers congresses in Rome in 1956 and Paris in 1959, for it had the advantage of being held on African soil. The chief organizer and the brain behind the gathering, Mphahlele built bridges both between continental African writers and between them and diasporic African writers from America and the Caribbean. The 1962 conference was a continuation of the bridge he himself had become. As the fiction editor of DRUM magazine in the fifties, he had been the link and mediating consciousness between the older generation of Mqhayi, Vilakazi, the Dhlomo brothers, and Peter Abrahams and the younger generation of tough- minded urbanites: Can Themba, Arthur Maimane, Lewis Nkosi, Bloke Modisane, Casey Motsisi, and Todd Matshikiza.

Even if he had stopped at Makerere, the university in Kampala where the conference was held, Mphahlele would still have made an indelible mark on the African literary scene and intellectual production. But he became a bridge between the creative and the scholarly, for in addition to creating platforms for writers, he also fought for the recognition of their product, African literature, in the academy. He followed up the success of the Makerere conference with another at Fourah Bay, in Sierra Leone, this time on the teaching of African literature at the university. Was he discouraged by finding no immediate takers for his ideas on the teaching of African literature in the academy? He obviously did not show it, because in 1966 he took the struggle to colonial Zambia after successfully persuading the English Department in Nairobi to let him teach a course on African literature.

CLASSICS

CLASSICS