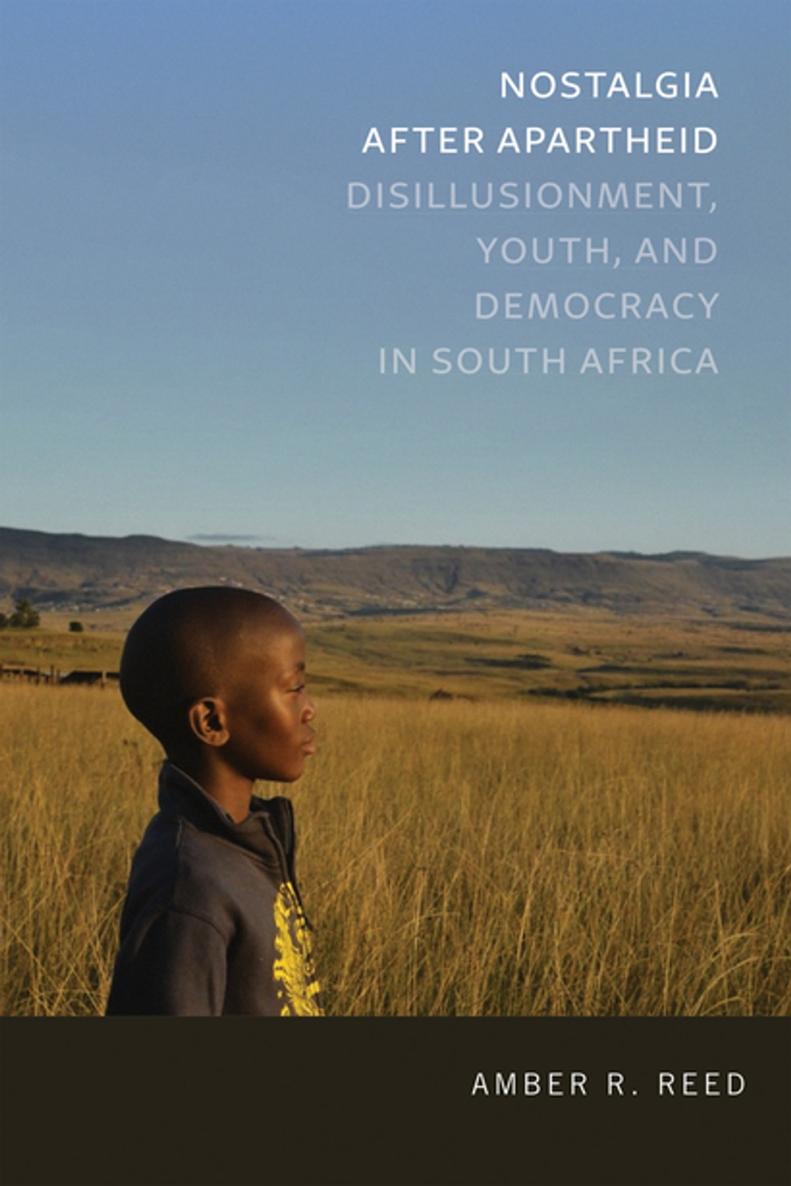

NOSTALGIA AFTER APARTHEID

RECENT TITLES FROM THE HELEN KELLOGG INSTITUTE SERIES ON DEMOCRACY AND DEVELOPMENT

Paolo G. Carozza and Anbal Prez-Lian, series editors

The University of Notre Dame Press gratefully thanks the Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies for its support in the publication of titles in this series.

Erik Ching

Authoritarian el Salvador: Politics and the Origins of the Military Regimes, 18801940 (2014)

Brian Wampler

Activating Democracy in Brazil: Popular Participation, Social Justice, and Interlocking Institutions (2015)

J. Ricardo Tranjan

Participatory Democracy in Brazil: Socioeconomic and Political Origins (2016)

Tracy Beck Fenwick

Avoiding Governors: Federalism, Democracy, and Poverty Alleviation in Brazil and Argentina (2016)

Alexander Wilde

Religious Responses to Violence: Human Rights in Latin America Past and Present (2016)

Pedro Meira Monteiro

The Other Roots: Wandering Origins in Roots of Brazil and the Impasses

of Modernity in Ibero-America (2017)

John Aerni-Flessner

Dreams for Lesotho: Independence, Foreign Assistance, and Development (2018)

Roxana Barbulescu

Migrant Integration in a Changing Europe: Migrants, European Citizens, and Co-ethnics in Italy and Spain (2019)

Matthew C. Ingram and Diana Kapiszewski, eds.

Beyond High Courts: The Justice Complex in Latin America (2019)

Kenneth P. Serbin

From Revolution to Power in Brazil: How Radical Leftists Embraced Capitalism

and Struggled with Leadership (2019)

Manuel Baln and Franoise Montambeault, eds.

Legacies of the Left Turn in Latin America: The Promise of Inclusive Citizenship (2020)

Ligia De Jess Castaldi

Abortion in Latin America and the Caribbean: The Legal Impact of the American Convention on Human Rights (2020)

For a complete list of titles from the Helen Kellogg Institute for International Studies, see http://www.undpress.nd.edu.

NOSTALGIA

AFTER

APARTHEID

Disillusionment, Youth, and

Democracy in South Africa

AMBER R. REED

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana

University of Notre Dame Press

Notre Dame, Indiana 46556

All Rights Reserved

Copyright 2020 by University of Notre Dame

Published in the United States of America

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020946988

ISBN: 978-0-268-10877-9 (Hardback)

ISBN: 978-0-268-10880-9 (WebPDF)

ISBN: 978-0-268-10879-3 (Epub)

This e-Book was converted from the original source file by a third-party vendor. Readers who notice any formatting, textual, or readability issues are encouraged to contact the publisher at

To Aphiwe

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

For a month or so in 2012, it seemed everyone in the rural Eastern Cape where I was conducting ethnographic research was talking about Jacob Zumas genitals. In May, two men had sneaked into a Johannesburg art gallery and used a red cross and black paint to deface Brett Murrays provocative painting of President Zuma, The Spear. The large canvas depicted the president in a style reminiscent of Lenin-era Soviet propaganda, only with his genitals fully exposed. Nationwide calls for the paintings removal (including from Zuma himself) and the subsequent act of vandalism were premised on the notion that this painting went too far, that it was an abuse of the constitutional right to artistic expression and free speech in its overt sexuality and visible disparaging of the nations president. Protests erupted throughout the country on both sides of the issue. A complicated series of court cases and appeals followed in the subsequent months, ultimately upholding the gallerys right to continue to display the painting (Laing 2012). During the time of this controversy, I was living with a Xhosa family in a small hilltop village just outside of the rural Eastern Cape town of Kamva. People in the area were almost unanimous in their anger over the paintings creation and display. They kept repeating the same sentiment to me: Human rights are important, but they must not be abused to the point of insulting someones dignity. In other words, they felt that there is a limit to individual rights and that their fellow citizens had crossed the line by supporting the painting.

This incident, and the reactions of Kamva residents to it, encapsulated much of the broader issues I was investigating in rural South Africa. On the one hand, the countrys recent overthrow of the apartheid state and embrace of liberal human rights saw freedom of expression as central to a healthy democracy. After decades of government censorship along racial lines, the ability to criticize even the highest office was essential. On the other hand, many South Africans found these liberal messages at odds with local value systems. People in Kamva said it was against their culture to so greatly insult a figure of authority like the president. What we see in twenty-first-century South Africa, then, is a country where national values of liberal democracy are often resisted on the grounds of culture in local settings. So, I wondered, what happens when local residents, often deeply invested in these acts of cultural resistance, are the ones tasked with teaching democracy to young people?

I did not set out to write a book about democracy, and I certainly did not expect to be writing about nostalgia for one of historys most reviled, racist systems of governance expressed by those who arguably suffered most at its hands. When I began ethnographic research in rural South Africas Eastern Cape Province, I was interested in the ways that young people both were affected by and contributed to the agendas of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), particularly those seeking to promote ideological and cultural change in rural areas far removed from the centers of government (Reed 2011; Reed and Hill 2010). I wanted to understand the role of NGOs in constructing or inhibiting youth agency and activism, but it very quickly became apparent that this focus was far too narrow to capture the lives of young rural South Africans. During the many conversations I had with activists, parents, teachers, and young people in the Eastern Cape, I kept getting steered toward the perceived cultural intrusions of Western-influenced democracy as it played out in local contexts and the resulting nostalgia for apartheid as a time of security, social control, and greater cultural freedom. For my research participants, NGOs seeking to enact ideological change became a conversational entry point into larger expressions of immense frustration with the status quo and anger over the push for an unpalatable version of democracy. Freedom, it turned out, did not feel so free; instead, it rested on Western ideas of personhood and subjectivity that felt confining, imposing, and alien. To make matters worse, these political changes were paired with dashed hopes for socialist economic policies and increased wealth inequalities via neoliberal channels of governance. As many anthropologists have done before me, I adjusted my focus to what people wanted me to talk about rather than the other way around. Conversations about the future were sidelined in order to make way for stories about the past.

Since the early 1960s, African states have thrown off the official yoke of colonialism in relatively quick succession, rapidly and drastically changing the political landscape of the continent. Many of these revolutionary movements became pawns in the Cold War scramble for influence on the African continent, and thus governmental aspirations often took on socialist or communist angles. With the fall of the Soviet Union, however, much of Africa was swept up into the dual global trends of liberal representative democracy and neoliberal economics, two sets of ideas that have become naturalized and seemingly inextricable in the view of many people in the twenty-first century. Despite the fervent hope and excitement imbued in postcolonial democratic movements and Pan-African alliances across the continent, both news reports and scholarly analyses have shown us the myriad problems with trying to adapt Western systems of governance, morality, and justice to diverse African contexts with complex racial, cultural, and political historiesnot to mention the challenge of deepening inequalities wrought by the new economic order and sustained by the legacies of colonialism.