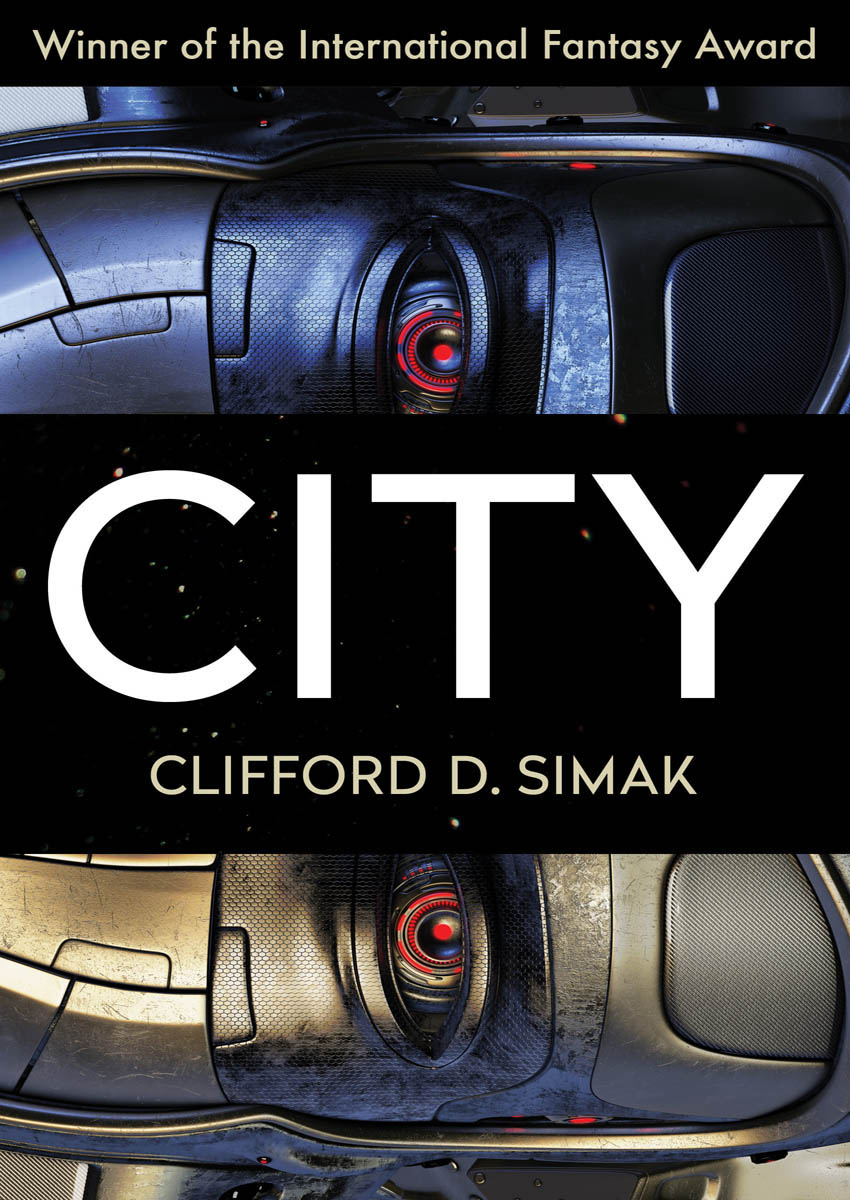

City

Clifford D. Simak

All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this book or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

These are works of fiction. Names, characters, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

City is based on material originally copyrighted by Street & Smith Publications, Inc. City, Huddling Place, Census, 1944. Paradise, Hobbies, 1946, Aesop, 1947. Trouble With Ants, copyrighted by Ziff-Davis Publishing Co., 1951.

Copyright 1952, 1980 by Clifford D. Simak

Cover design by Jason Gabbert

978-1-5040-1294-2

This edition published in 2015 by Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

180 Maiden Lane

New York, NY 10038

www.openroadmedia.com

In Memory of Scootie, Who Was Nathaniel

CONTENTS

EDITORS PREFACE

These are the stories that the Dogs tell when the fires burn high and the wind is from the north. Then each family circle gathers at the hearthstone and the pups sit silently and listen and when the storys done they ask many questions:

What is Man? theyll ask.

Or perhaps: What is a city?

Or: What is a war?

There is no positive answer to any of these questions. There are suppositions and there are theories and there are many educated guesses, but there are no answers.

In a family circle, many a storyteller has been forced to fall back on the ancient explanation that it is nothing but a story, there is no such thing as a Man or city, that one does not search for truth in a simple tale, but takes it for its pleasure and lets it go at that.

Explanations such as these, while they may do to answer pups, are no explanations. One does search for truth in such simple tales as these.

The legend, consisting of eight tales, has been told for countless centuries. So far as can be determined, it has no historic starting point; the most minute study of it fails entirely to illustrate the stages of its development. There is no doubt that through many years of telling it has become stylized, but there is no way to trace the direction of its stylization.

That it is ancient and, as some writers claim, that it may be of non-Doggish origin in part, is borne out by the abundance of jabberwocky which studs the taleswords and phrases (and worst of all, ideas) which have no meaning now and may have never had a meaning. Through telling and retelling, these words and phrases have become accepted, have been assigned, through context, a certain arbitrary value. But there is no way of knowing whether or not these arbitrary values even approximate the original meaning of the words.

This edition of the tales will not attempt to enter into the many technical arguments concerning the existence or nonexistence of Man, of the puzzle of the city, of the several theories relating to war, or of the many other questions which arise to plague the student who would seek in the legend some evidence of its having roots in some basic or historic truth.

The purpose of this edition is only to give the full, unexpurgated text of the tales as they finally stand. Chapter notes are utilized to point out the major points of speculation, but with no attempt at all to achieve conclusions. For those who wish some further understanding of the tales or of the many points of consideration which have arisen over them there are ample texts, written by Dogs of far greater competence than the present editor.

Recent discovery of fragments of what originally must have been an extensive body of literature has been advanced as the latest argument which would attribute at least part of the legend to mythological (and controversial) Man rather than to the Dogs. But until it can be proved that Man did, in fact, exist, argument that the discovered fragments originated with Man can have but little point.

Particularly significant or disturbing, depending upon the viewpoint that one takes, is the fact the apparent title of the literary fragment is the same as the title of one of the tales in the legend here presented. The word itself, of course, is entirely meaningless.

The first question, of course, is whether there ever was such a creature as Man. At the moment, in the absence of positive evidence, the sober consensus must be that there was not, that Man, as presented in the legend, is a figment of folklore invention. Man may have risen in the early days of Doggish culture as an imaginary being, a sort of racial god, on which the Dogs might call for help, to which they might retire for comfort.

Despite these sober conclusions, however, there are those who see in Man an actual elder god, a visitor from some mystic land or dimension, who came and stayed awhile and helped and then passed on to the place from which he came.

There still are others who believe that Man and Dog may have risen together as two co-operating animals, may have been complementary in the development of a culture, but that at some distant point in time they reached the parting of the ways.

Of all the disturbing factors in the tales (and they are many) the most disturbing is the suggestion of reverence which is accorded Man. It is hard for the average reader to accept this reverence as mere story-telling. It goes far beyond the perfunctory worship of a tribal god; one almost instinctively feels that it must be deep-rooted in some now forgotten belief or rite involving the pre-history of our race.

There is little hope now, of course, that any of the many areas of controversy which revolve about the legend ever will be settled.

Here, then, are the tales, to be read as you see fitfor pleasure only, for some sign of historical significance, for some hint of hidden meaning. Our best advice to the average reader: Dont take them too much to heart, for complete confusion, if not madness, lurks along the road.

Introduction

Clifford D. Simak did not dedicate his books very often, but he dedicated this oneto his dog. He loved dogs, and he made them prominent features of a number of his storiesand in this case he made it clear that the dog in question, Scootie, was the model for Nathaniel, who can be found in Census, the third episode in this book, and who became legend to succeeding generations of dogs.

Scootie was, yes, a Scottiea black one (there is a photograph to prove it).

And yet, although dogs and a robot dominate the memories of this book for generations of readers, no dog appears in its first episode, City, nor does any robot, unless you want to count an automatic lawn mower.

This book, City , is undoubtedly one of the classics of the science fiction field; its images of talking dogs, of humans abandoning Earth, of a guardian robot, and of intelligent ants are iconic even today, more than sixty years after those concepts were created.

But City (the book) was not created as most novels are; rather, it was written bit by bit, in the form of eight short stories seemingly intended only for magazine publications across a string of nearly nine years beginning in 1943. (A ninth story would be added to the canon twenty-one years after the books publication in 1952 and then only because the author felt himself to have no choice but to do so; see his comments preceding that last story, Epilog.)