Contents

Guide

Page List

To Mary

The thing hath been from the Creation of the

World, but hath not so been explained as that

the interior Beauty of it should be understood.

Thomas Traherne (c.163674)

Contents

Preface

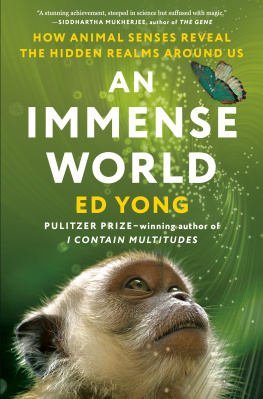

Right now, a crow is flying past my window. It looks purposeful, heading off on some mission known only to itself. A bumblebee is methodically visiting flowers in the garden. A butterfly flaps quickly over the wall, careers around wildly, settles for an instant, and then flies on. A cat walks along the path and slips into the undergrowth, while overhead an airliner packed with people makes its descent toward Heathrow.

Just look around you. Animals, large and small, human and nonhuman, are on the moveeverywhere. They may be looking for food, or a mate; they may be migrating to avoid the winters cold or the summers heat; or they may just be heading home. Some make journeys that span the globe, while others only putter around their neighborhood. But whether you are an arctic tern flying from one end of the earth to the other, or a desert ant dashing back to its nest with a dead fly in its jaws, you must be able to find your way. It is quite simply a matter of life and death.

When a wasp flies off on a hunting expedition, how does it find its nest again? How does a dung beetle roll its ball of dung in a straight line? After circling an entire ocean, what strange sense guides a sea turtle back to the beach where she was born to lay her eggs? When a pigeon is released hundreds of miles away from its loft, in a place it has never gone near before, how can it find its way home? And what about the indigenous peoples who still, in some parts of the world, make long and difficult journeys by sea and land without so much as a map or compass, let alone GPS?

The first question I want to address in this book is simply this: How do animalsincluding humansfind their way around? As you will see, the answers are fascinating in themselves, but they prompt further questions that touch on our changing relationship with the world around us. We humans are abandoning the basic navigational skills on which we have relied for so long. We can now fix our position effortlessly and precisely, anywhere on the surface of the planet, without even thinkingat the press of a button. Does that matter? We do not yet know for sure, but in the concluding chapters I shall explore the issues that are at stake. They are important.

Before we get started, a few words about everyday navigational challenges may help to prepare the ground. So, consider for a moment how you cope when you arrive by airplane in a strange city.

Your first navigational task is to find the way from the aircraft through immigration to the baggage hall. Even this kind of indoor navigation can present problems, especially if your vision is impaired, but we can usually overcome them by following signs. Once you are sitting in the taxi or bus, you can relax and let the driver make the decisions.

On arriving at your hotel, you have to find the check-in desk and locate your roomagain signs are a big help. In the morning you may want to explore the neighborhood on foot. The beguiling voice of your GPS-enabled cell phone could give you exact directions, but that is not real navigation: You are being told what to do.

If you are independent-minded and prefer to find your own way, you will probably reach for a printed map. The first practical challenge is to place your hotel on the mapin other words, to determine your position. Next you need to find the sights you want to visit and work out how to reach them and how long it will take. That means measuring distances and estimating your likely speed, which raises the issue of measuring time. Though it may not at first seem obvious, navigation is as much concerned with time as space.

That will do for journey planning. Now you face another problem: when leaving your hotel do you turn right or left? You need to know which way you are facing before you can set off on your journey. There are various ways of solving this key problem. You could refer to the compass built into your phone, but you could also orient yourself by working out what street you are on. Looking at the shadows to see where the sun is might help, too. Then, once you start walking, you will need to keep track of your progress by checking landmarks and street names against the map.

As you make more and more excursions, you will start to grasp the layout of the cityhow each part connects with its neighbors. This is a matter of remembering landmarks and establishing the geometrical relationships between them. As we all know, some people are much better at finding their way around than others, but if you are adept at this kind of navigation, you will develop the confidence to make longer and more complicated journeys without even looking at the map, and instead of merely going to and from your hotel, you may start to follow routes that connect different areas of the city with each other. By now you will have acquired a mental map of the city.

But you may employ a very different navigational technique. Instead of using a map, you could simply follow your nose until you find something that interests you, all the while keeping a close eye on which way you are going and how far you have gone, so that you can safely find your way back to your hotel.

This process has been likened to the method employed by the legendary Greek hero Theseus. As he entered the Minotaurs labyrinth, he unwound the ball of thread given to him by Ariadne, and it was this clue that enabled him to retrace his steps after killing the monster. A ball of thread is not a very practical navigational tool in a busy modern city, so in practice, navigation without a map depends on close observation and memory.

The distinction between navigating with and without the help of a map is a crucial one, and it extends to nonhuman animals. Maps (whether physical or mental) offer great advantages, not east the possibility of constructing shortcuts that can save valuable time and energy, or making detours to avoid hazards and obstacles. Some animals do seem to use maps of some kind (though obviously they are not printed on paper), but this is hard to prove, and discovering how such maps work is trickier still. These are some of the deepest questions faced by scientists exploring the navigational abilities of animals.

The structure of this book reflects the distinction between non-map and map-based navigation. In the first part, I focus on how animals can navigate without maps, and in the second, I discuss the possible use of mapsof various kinds, by different animalsand the evidence for the existence of map-like representations of the world in their brains. In the final part, I consider what the science of animal navigation means to us.

Each chapter is separated from the next by a short passage in italics that introduces some example of animal navigationusually a puzzling onethat could not be comfortably accommodated in the main narrative. These will, I hope, help to entertain the reader, while also revealing how many mysteries remain to be solved.

Animal navigation is a big, complicated area of research, and in a short book like this I can only highlight some of its main themes. It is far from being an exhaustive account of the subject, and because it is aimed at the general reader, rather than a specialist audience, I have avoided the use of technical terms as far as possible.