Contents

Guide

In loving memory of Rob Avery

Thanks

Eternal love and sunshine to Jess, Romy & Mae

To the Sewells, the Roses, the Lees and the OSullivan-Averys

To the NHS nurses and Covid key workers

And to all the spotters and jotters that made Lockdown 0.1 so much fun!

Contents

Introduction

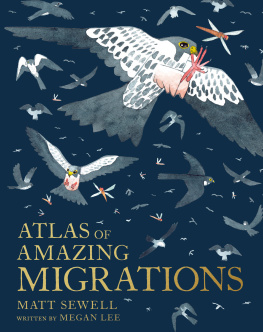

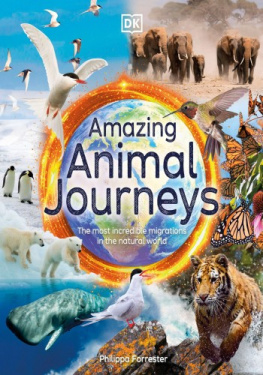

This book looks at some of the most amazing, arduous and downright clever migrations of creatures ranging from birds to mammals, insects to fish, and even some plants. Creatures migrate from one part of the planet to another mainly to find food or warmth, or to reproduce, or sometimes for some other mysterious reason were yet to discover.

Their journeys range from treks of thousands of kilometres across continents and oceans, to crossing the road (which might sound simple to us, but is an ordeal in itself if youre a snake or a toad, and the road is packed with speeding cars (see ), migration can take up to five generations, as parent gets replaced by child then grandchild and so on, as the journey continues.

Migration seems to be written into the genes of animals, so that they know when to travel and where to. Without the sat navs we lucky humans have, creatures use a variety of methods to navigate their routes, including magnetic fields, temperature and light. One study found that some birds seem to use the stars to navigate, just like sailors of old. In this book, we have also mapped some of the most amazing migrations, showing the approximate routes. Not all of the migrations in this book have been mapped and those that have may sometimes deviate from the journeys weve shown, but we wanted to give a sense of how stunning many of these migrations really are.

We all know that nature is an amazing thing, but just read some of these stories and youll be stunned by the stamina, strength and smartness of these creatures and the lengths they go to in their migrations. And once youve seen what these animals and plants go through, I hope you wont start complaining next time your trip to the shops takes longer than usual!

Cougar

Puma concolor

At one time, this beautiful big cat could be found slinking all over North America. Now it is rarely found outside western regions of Canada, Mexico and the United States, but its thanks to migration that the cougar ever made it to the continent at all. It is thought that its ancestor migrated to the Americas millions of years ago by crossing the Bering land bridge, a strip of land that once connected Asia to North America. From this adventurous ancestor came all the cougars, lynx and wildcats that now stalk the region. The cougar, or mountain lion as it also answers to, is mysterious and solitary. Each cat has a large territory all to itself, and spends most of its life roaming alone (although mothers and cubs, tightly bonded, will wander together for a while).

A natural drifter, the cougar doesnt have a permanent den, and will happily crash out in dense vegetation or take a kip in a cave before moving on. It can get on well in almost any habitat, from mountains to deserts to forests, but as winter threatens it will tend to migrate further into the mountains where it is easier to hunt. Although many people claim to catch glimpses of a cougar prowling about eastern areas of the United States, chances are good that nearly every time its probably a bobcat, or just a very big dog. Outside of Florida, eastern cougars are considered to be mostly gone. There is however some evidence that mountain lions may be making a comeback in the east. One cougar was tracked migrating all the way to Connecticut from South Dakota, wandering some 2,900km before sadly being hit by a car.

If cougar numbers are on the rise, it could be that they are being driven closer to humans as they attempt to avoid crossing paths with each other. Perhaps we will start to see more of these secretive, wayfaring felines turning up in places where they have long been out of sight.

Basking shark

Cetorhinus maximus

If youve ever been told off for eating with your mouth open, youre in good company with the basking shark. These massive sharks can be found all over the world in arctic and temperate waters, and migrate closer to the shore during the summer where they bask (swimming slowly with their large mouths wide open). Swimming along in what looks like a suspended yawn or silent bellow may make them look unusual to us, but the basking shark knows what it's doing. This shark loves to feast on zooplankton, and by swimming through a patch of the stuff with an open mouth (a technique that is known as filter feeding) it is able to capture the plankton using its gill rakers. With its mouth agape like a swollen rib cage, the basking shark can filter almost 2,000 tons of water an hour. Thats quite a mouthful!

Basking sharks may be the second largest fish in the world, but boy do they keep to themselves. If you see one in shallow water you might be able to clock just a peep of dorsal fin and snout cutting through the water's surface, but when they migrate to deeper waters in winter they are a highly elusive species.

The patterns of their migration have largely remained a mystery, but they are known to be able to tackle large distances and will even cross oceans. One tagged basking shark travelled 9,500km from the Isle of Man to Canada, reaching a record depth of 1,264m on its way. The sharks massive liver, which can contribute up to a third of its body weight and is filled with an oil called squalene, increases its buoyancy and provides bags of energy that can be used to fuel these huge journeys. Why they travel so far is still unknown, but they could be looking for good places to mate or feed, or even trying to find water thats the ideal temperature.

Wildebeest

Connochaetes taurinus

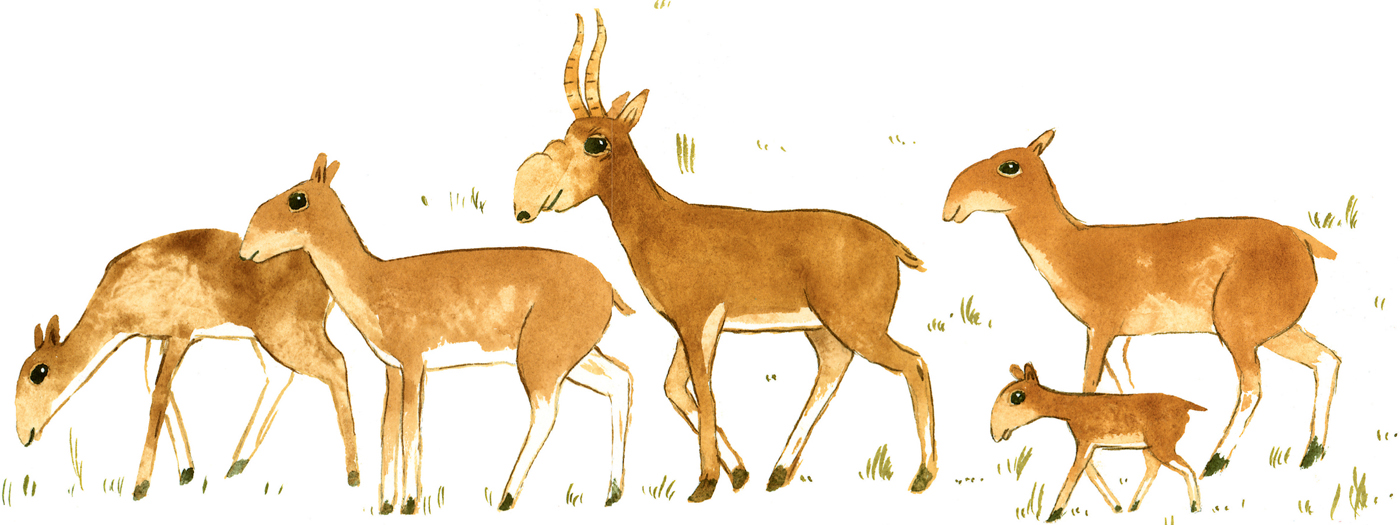

This is the common wildebeest, although if youd like you can simply call it the gnu. Its no wonder its name translates to wild beast. As far as antelope go, this guy looks rather intimidating, with two sharp, curved horns jutting out of its massive head and a dark, shaggy mane running down its hunched back. It grazes constantly on Africas grassy plains, munching away through the day and night.

Living in such a hot place means the wildebeest relies on rainfall for enough grass to eat, and changes in the weather push it to migrate in a massive, clockwise loop each year. It sets off with hearty numbers of zebra, gazelle and impala, but the wildebeest is undoubtedly the star of this show.

As the wet season ends around May or June, some 1.5 million hungry and thirsty wildebeest put on a mind-blowing performance, chasing the rain north around the Serengeti towards Masai Mara. They form a big clan, as up to 500,000 of their calves are born just months before this event. Unlike human babies that flail around on their backs for months, wildebeest calves can walk within minutes of being born! Its a good job too, as they need to be able to keep up with the herd. The wildebeest charge together in a chaotic, swirling mass of muscle, pelt and pure drive, thundering over the land on a dangerous journey. Although their huge numbers provide them with some safety, this doesnt stop many of them from dying along the way. Each year more than 250,000 gnu are taken out by predators like lions and hyenas, or caught by cattle fences that are popping up more and more across Africa.