ALSO BY KITTY BURNS FLOREY

SOLOS

SOUVENIR OF COLD SPRINGS

FIVE QUESTIONS

VIGIL FOR A STRANGER

DUET

REAL LIFE

THE GARDEN PATH

CHEZ CORDELIA

FAMILY MATTERS

2006 KITTY BURNS FLOREY

BOOK DESIGN:

DAVID KONOPKA

ILLUSTRATION:

JOEL HOLLAND,

WWW.JMHILLUSTRATION.COM

MELVILLE HOUSE PUBLISHING

145 PLYMOUTH STREET

BROOKLYN, NEW YORK 11201

AND

8 BLACKSTOCK MEWS

ISLINGTON

LONDON N4 2BT

WWW.MHPBOOKS.COM

FIRST MELVILLE HOUSE PRINTING

OCTOBER 2006

ISBN: 978-1-61219-402-8 (EBOOK)

Portions of this book first appeared in an altered form in The Vocabula Review, Harpers Magazine, and Best American Essays 2005, edited by Susan Orlean and published by Houghton Mifflin.

Photo of Brainerd Kellogg used by permission of the Polytechnic University Archives.

The photo Alonzo Reed and his wife in front of Seatuck Lodge is from A History of Remsenburg (2003) published by and used with the permission of The Remsenburg Association, Inc.

The photo Gertrude Stein and one of the Baskets is courtesy of The Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

The photographs on are courtesy of Maya Fineberg.

The poem A Dog from Tender Buttons 1914 by Gertrude Stein is used by permission of Stanford G. Gann, Jr., Literary Executor of the Estate of Gertrude Stein.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE HARDCOVER EDITION OF THIS BOOK AS FOLLOWS:

Florey, Kitty Burns.

Sister Bernadettes barking dog : the quirky history and lost art of diagramming sentences / Kitty Burns Florey.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-933633-10-7 (alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-933633-10-7 (alk. paper)

1. English language Sentences. 2. English languageGrammar. 3. English language Syntax. I. Title.

PE1375F56 2006

428.2dc22

2006024703

v3.1

chapter 1

ENTER THE DOG

Even in my own youth, many years after 1877, diagramming was serious business. I learned it in the sixth grade from Sister Bernadette.

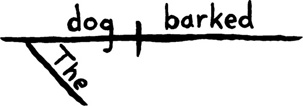

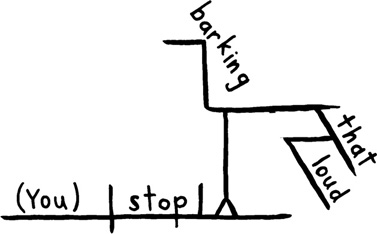

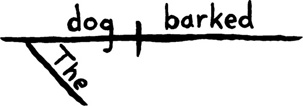

Sister Bernadette: I can still see her, a tiny nun with a sharp pink nose, confidently drawing a dead-straight horizontal line like a highway across the blackboard, flourishing her chalk in the air at the end of it, her veil flipping out behind her as she turned back to the class. We begin, she said, with a straight line. And then, in her firm and saintly script, she put words on the line, a noun and a verbprobably something like dog barked. Between the words she drew a short vertical slash, bisecting the line. Then she drew a roada short country lanethat forked off at an angle under the word dog, and on it she wrote The.

That was it: subject, predicate, and the little modifying article that civilized the sentenceall of it made into a picture that was every bit as clear and informative as an actual portrait of a beagle in mid-woof. The thrilling part was that this was a picture not of the animal but of the words that stood for the animal and its noises. It was a representation of something that was both concrete (we could hear the words if we said them aloud, and they conveyed an actual event) and abstract (the words were invisible, and their sounds vanished from the air as soon as they were uttered). The diagram was the bridge between a dog and the description of a dog. It was a bit like art, a bit like mathematics. It was much more than words uttered, or words written on a piece of paper: it was a picture of language.

I was hooked. So, it seems, were many of my contemporaries. Among the myths that have attached themselves to memories of being educated in the 50s is the notion that activities like diagramming sentences (along with memorizing poems and adding long columns of figures without a calculator) were draggy and monotonous. I thought diagramming was fun, and most of my friends who were subjected to it look back with varying degrees of delight. Some of us were better at it than others, but it was considered a kind of treat, a game that broke up the school day. You took a sentence, threw it against the wall, picked up the pieces, and put them together again, slotting each word into its pigeonhole. When you got it right, you made order and sense out of what we used all the time and took for granted: sentences. Those ephemeral words didnt just fade away in the air but became chiseled in stoneyes, this is a sentence, this is what its made of, this is what it looks like, a chunk of English you can see and grab onto.

I remember loving the look of the sentences, short or long, once they were tidied into diagramsthe curious geometric shapes they made, their maplike tentacles, the way the words settled primly along their horizontals like houses on a road, the way some roads were culs de sac and some were long meandering interstates with many exit ramps and scenic lookouts. And the perfection of it all, the ease with whichonce they were laid open, all their secrets exposedthose sentences could be comprehended.

On a more trivial, pre-teen level, part of the fun was being summoned to the blackboard to show off your skills. There youd be with your chalk while, with a glint in her eye, Sister Bernadette read off an especially tricky sentence. Compact, fastidious handwriting was an asset. A good spatial sense helped you arrange things so that the diagram didnt end up jammed against the edge of the blackboard like commuters in a subway car. The trick was to think fast, write fast, and try not to get rattled if you failed nobly in the attempt.

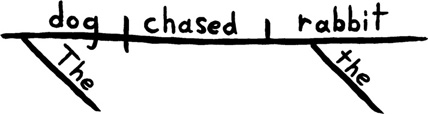

As we became more proficient, the tasks got harder. There was great appeal in the Shaker-like simplicity of sentences like The dog chased the rabbit (subject, predicate, direct object) with their plain, no-nonsense diagrams:

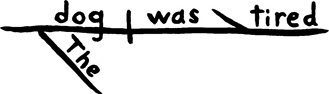

But there were also lovable subtleties, like the way the line that set off a predicate adjective slanted back toward the subject it referred to, like a signpost or a pointing finger:

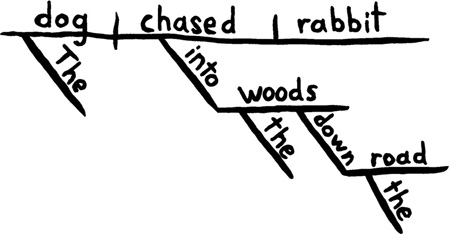

Or the thorny rosebush created by diagramming a prepositional phrase modifying another prepositional phrase:

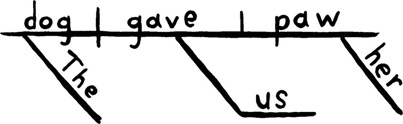

Or the elegant absence of the preposition with an indirect object, indicated by a short road with no house on it:

as in: