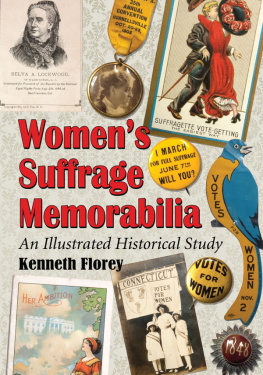

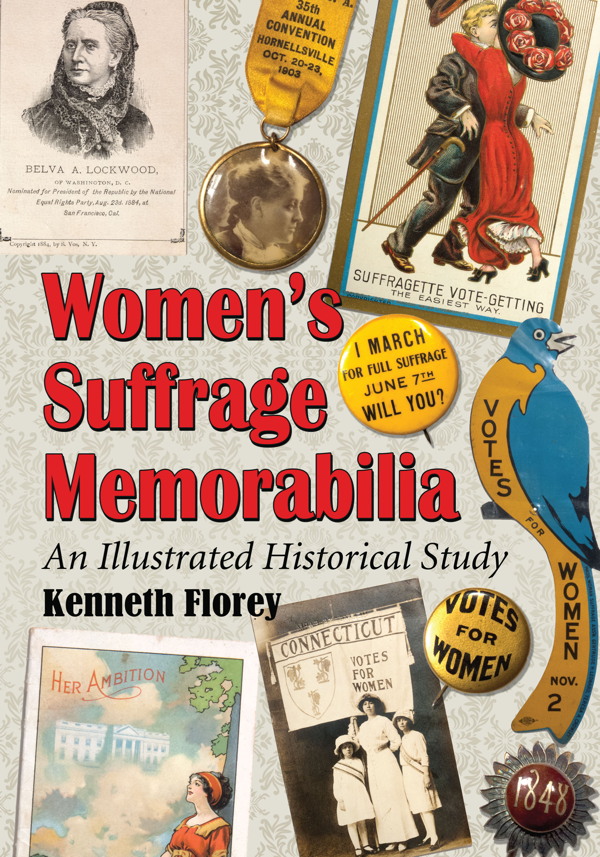

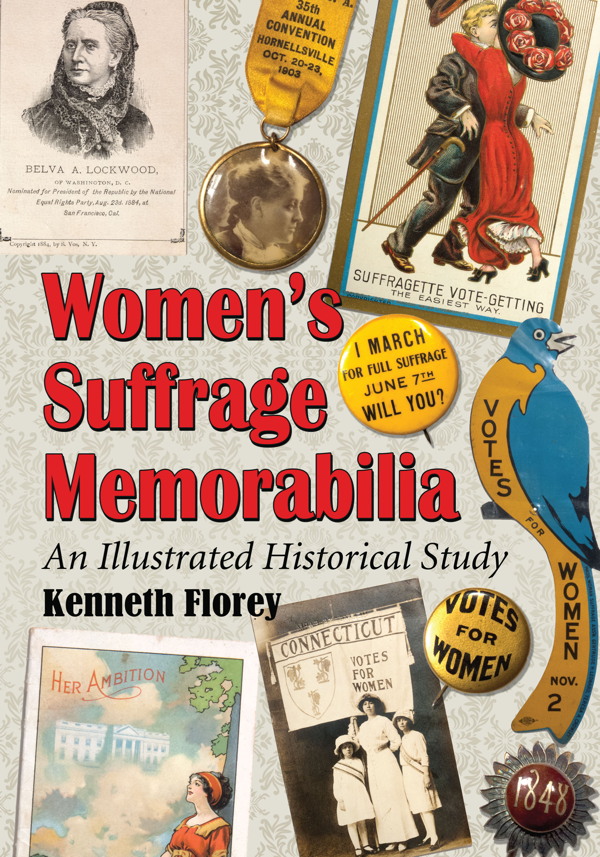

Womens Suffrage Memorabilia

An Illustrated Historical Study

Kenneth Florey

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-0150-2

2013 Kenneth Florey. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: clockwise from top left Belva Lockwood official campaign card; Carrie Chapman Catton, a New York State Womans Suffrage Association button; card from Suffragette series, Dunston Weiler Lithograph Co., 1909; button advertising the 1908 Rochester, N.Y., march; 1915 Tin Bird Eastern campaign advertisement; 1848 Suffragette hat pin; Votes for Women American suffrage button; Connecticut Woman Suffrage Associations Mrs. Toscan Bennett, pictured here with her children; Advertising Booklet for the Brown Shoe Co. (all objects from authors collection photographed by Paul D. Sprague); background floral wallpaper (Ingram Publishing/Thinkstock)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Emmy, Katherine, Genevieve, Sean, and Miranda,

who of all the wonderful people in my life are my favorites

Preface and Acknowledgments

The purpose of this study is to provide the historian not only with a detailed survey of the various types of memorabilia and artifacts that were produced during the suffrage period, but also with a discussion of the context and history of those types, including their signicance and meaning to the suffragist movement. I have examined suffrage pamphlets and journals, period newspapers, magazines and books, and assorted library clippings, along with various period sales lists for accounts both of the production and distribution of memorabilia and for the various reactions of suffragists, their supporters, and the public at the time to these various artifacts of history. Additionally, I have had access in preparing this manuscript not only to my own collection of suffrage material, which is extensive, but also to those of valued friends, whose holdings of womens rights memorabilia are among the largest currently in private hands in America.

Suffrage scholars have long been aware of the importance of suffrage novelties to the movement, and have alluded to them in their studies, but often have had little personal experience in dealing with the objects close at hand; thus, their analyses of suffrage artifacts have necessarily been limited. Part of the difculty is that such objects generally are scattered widely about, and comprehensive collections of suffrage artifacts can be quite difcult to access, even though some museums in both America and England do have impressive holdings in limited areas. Another problem is that most scholars do not have ready knowledge of the general nature and history of the type of objects (postcards, badges, advertising cards, valentines, etc.) that suffragists both ordered and sold to advance the cause. To a degree, one must know something about the developing traditions of celluloid buttons, postcards, sheet music, collectors spoons, various types of souvenir photography, campaign pennants, Cinderella stamps, and other forms of memorabilia to appreciate the ways in which suffragists utilized and manipulated the potential of these forms to help achieve their ultimate goals.

This study attempts in part to address both problems by providing numerous photographs of suffrage memorabilia in concert with discussion about that memorabilia. Whenever possible, I also have included information about which organization produced what material, production numbers, and the original purchase price for items in single quantities and sometimes also in bulk. Production numbers have much to say about the relative importance of different and sometimes competing items to suffrage supporters. Specic objects, too, often have a fascinating history, a fact reected in the abundant stories about campaign memorabilia that appeared not only in suffrage publications but also in period commercial venues such as newspapers and magazines. The pages of the major suffrage papers and journals such as the Womans Journal, The Suffragist, Votes for Women, and, to a degree, Woodhull and Clains Weekly as well as Susan B. Anthonys The Revolution were lled with stories and pictures of new memorabilia and the excitement that a recent button, postcard, photograph or ribbon had generated among supporters.

The focus of this book is on American objects, but I have included signicant material from the British campaign as well. Suffrage in a larger context was an international movement, and American suffragists were in constant contact with activists abroad. American women borrowed much from their English counterparts, in terms not only of merchandising and marketing but also of iconography, slogans, and an understanding of the importance of the propagandistic and emotive value that ofcial colors held for any organization. It worked the other way too. American and English publications shared information, urging their readers to subscribe to journals from the other country, and activists on both sides of the Atlantic were quite aware of both innovative and provocative designs and of new novelties that had been created and manufactured by their counterparts across the ocean.

This study also examines to a degree the anti-suffrage material that was manufactured in abundance by both commercial sources and organizations of determined men hostile to the franchise, groups that were, at times, fronted by reactionary women. Often the struggle between those who supported and those who opposed suffrage was reected in a symbolic battle between the collectible ephemera that both sides produced. A pro-suffrage button, for example, would mimic an anti-suffrage effort. An anti-suffrage leader would complain about the sentiments expressed on a movement postcard that satirized their positions. Suffragists wearing sashes in their ofcial yellow color would dress up a dummy with apparel in the corresponding anti-suffrage red or pink and then rescue it from drowning, mocking the iconography of the opposition in the process.

Ultimately, what I hope emerges here is a portrait of the movement from a popular culture perspective. Literature published by suffragists tells us about the movements ideologies and strategies, but may reveal too little to us about its human side. Memorabilia, on the other hand, whether sent through the mails, preserved at home, displayed at conventions, or worn at marches and demonstrations, tells us something about the basic character of the suffragists themselves and of the organizations that manufactured and distributed these objects. The eagerness to buy, display, and collect specic memorabilia indicates that many suffrage sympathizers wanted, in part at least, to ingest the movement, to have it become part of them in a tangible way that was not otherwise possible through campaign literature and speeches alone.

I have arranged this study into sixty-nine different sections, each dealing with a specic subject, such as advertising cards, buttons and badges. I chose this approach because, I think, by isolating types of memorabilia into their own separate discussions, it provides easier access for the reader, thereby creating a structure for clearer denition and analysis. The term memorabilia is applied here to any object that was produced with any sort of keepsake value, however minimal, in addition to its suffrage message. The concept of keepsake value varies from individual to individual, and the inclusion of certain categories and the exclusion of others here is, obviously, arbitrary. In general, I have avoided discussing pamphlets, leaets, autographs, and books, even though one legitimately could regard such printed material as memorabilia also, although not quite in the same way that buttons, ribbons, sashes, and postcards are generally perceived. I also have included categories that are not specic types of memorabilia in and of themselves, but are nevertheless related to the topic. There were, for example, a variety of objects produced that were associated with the presidential campaigns of Belva Lockwood and Victoria Woodhull, each of which is discussed in a separate listing. The casting of a liberty bell by Pennsylvania women for their 1915 state campaign resulted in the appearance of several types of innovative memorabilia, and that event, along with its aftermath, is featured in a section all its own. Finally, any formal examination of suffrage artifacts would be remiss if it were not to include a discussion of ofcial suffrage colors and of suffrage stores, where much of the memorabila was dispensed, so those categories appear here also.

Next page