Public Faces, Secret Lives

Public Faces, Secret Lives

A Queer History of the Womens Suffrage Movement

Wendy L. Rouse

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2022 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rouse, Wendy L., author.

Title: Public faces, secret lives : a queer history of the womens suffrage movement / Wendy L. Rouse.

Description: New York : New York University Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021035988 | ISBN 9781479813940 (hardback) | ISBN 9781479813957 (ebook) | ISBN 9781479813964 (ebook other)

Subjects: LCSH : WomenSuffrageUnited StatesHistory. | SuffragistsUnited StatesHistory. | LesbiansPolitical activityUnited States.

Classification: LCC JK1896 .R68 2022 | DDC 324.6/230973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021035988

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

Contents

List of Figures

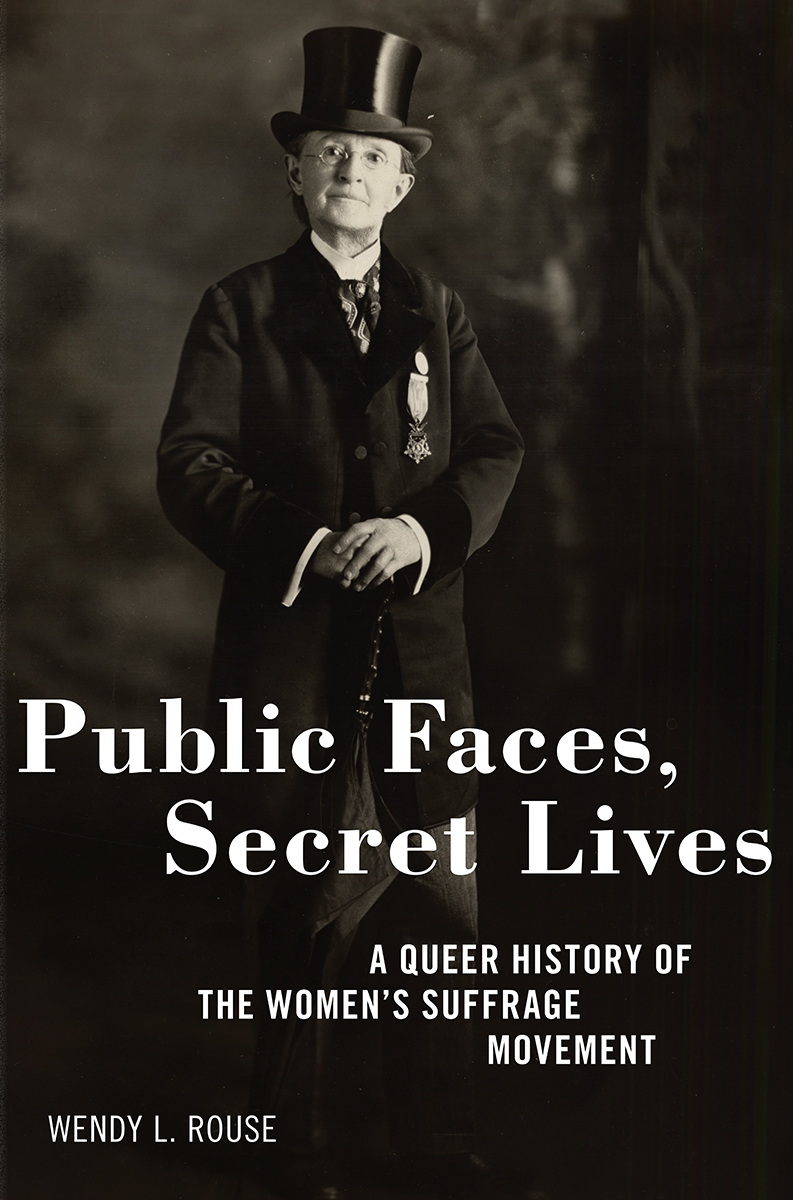

Figure I.1. Dr. Mary Walker

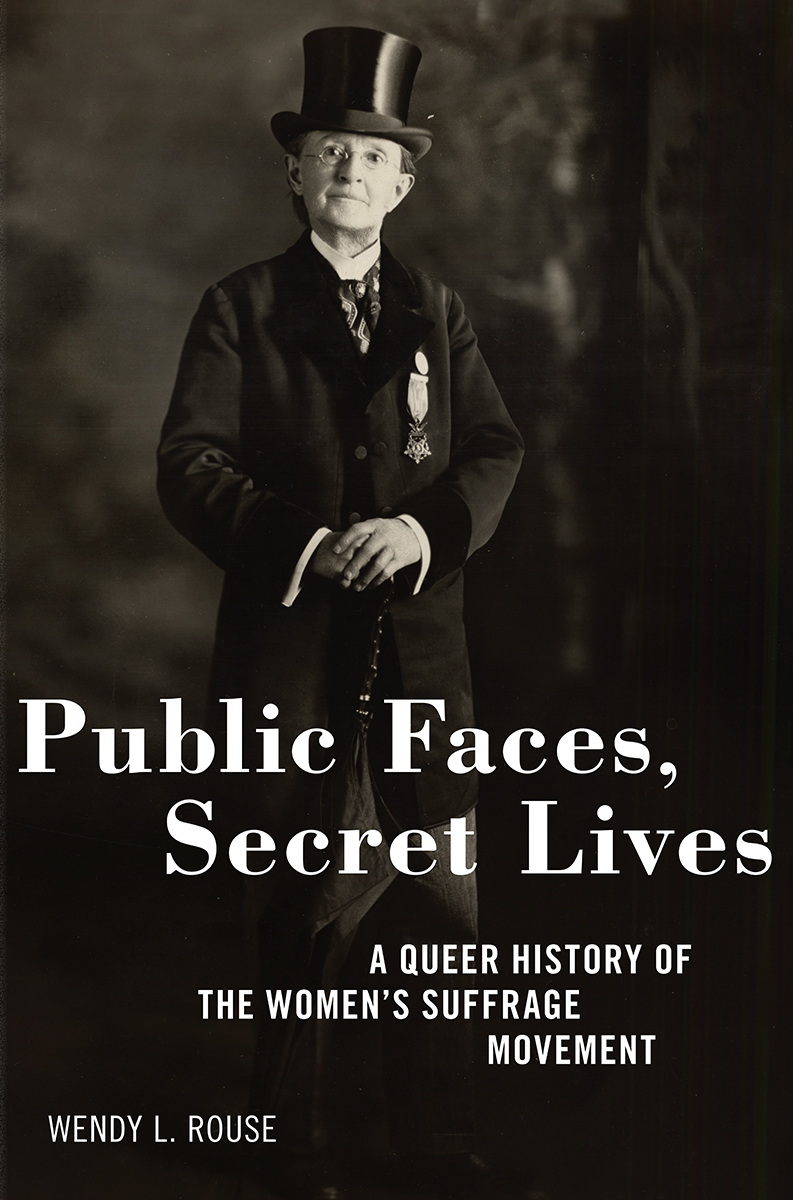

Figure I.2. Anna Howard Shaw

Figure 1.1. Miss Mannish

Figure 1.2. I Dont Like to See a Woman Do a Mans Work

Figure 2.1. Ida Blair and Aleda Richberg-Hornsby

Figure 2.2. Angelina Weld Grimk

Figure 2.3. Colored Suffrage Rally

Figure 3.1. Eugene De Forrest

Figure 3.2. Lucy Diggs Slowe and Mary Powell Burrill

Figure 4.1. Alice Morgan Wright

Figure 5.1. Kathleen De Vere Taylor

Figure 5.2. Dr. Josephine Baker

Figure 5.3. Myran Louise Grant

Figure 5.4. Annie Tinker

Figure 6.1. A Lasting Tribute to a Friend

Figure 6.2. Minnie Brown and Daisy Tapley

Figure 6.3. Headstone, Gail Laughlin and Dr. Mary Sperry

In 1873, Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, dressed in one of her characteristically gender-defying outfits, boldly walked onto the stage at the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) convention in Washington, DC. She stood there silently, waiting for Susan B. Anthony to yield the floor to her. Elizabeth Cady Stanton was visibly annoyed at Walkers presence and believed that since she was not on the program she should not be allowed to speak. Anthony, recognizing Walkers popularity with the crowd, eventually acquiesced and invited her to make remarks. Walker took the floor and immediately launched into a scathing critique of NWSA leadership for their failure to push for broader social reforms.

Walker specifically called out Stanton and Anthony for abandoning dress reform. Dress reformers advocated for womens right to wear comfortable and practical clothing, such as bloomers. Walker had endured multiple arrests in her commitment to the cause. She noted that Stanton and Anthony had given up dress reform because they lacked the courage to continue the fight. Walker told reporters that suffragists had now snubbed her because of her gender queer appearance: These women have shaken me off because I wear pants.

Walkers queer gender expression, unwavering commitment to dress reform, love of the spotlight, and condemnation of suffrage leaders and their methods, elicited the ire of mainstream suffragists. Walker was a Civil War surgeon and Medal of Honor recipient who spent her entire life fighting for womens rights and suffrage. Her choice to wear the reform dress and, later, mens clothing made her a target of open ridicule and harassment both inside and outside the movement. As an individual who stretched the limits of conventional notions of gender, Walkers life highlights both the marginalization of queer individuals and the centrality of queerness in the womens suffrage movement. But, this history has been largely erased.

The reality is that the womens suffrage movement was very queer, and queer suffragists were central figures in the movement. It is time that we tell their story. Scholars have extensively documented how the narrow focus on the stories of middle- and upper-class white women in the narrative of womens suffrage history ignores the important role of Black women, Indigenous women, working-class women, immigrant women, and women of color fighting for the vote. Similarly, I argue here that the narrow focus on cisgender heterosexual women erases the existence of queer suffragistsindividuals who transgressed normative notions of gender and sexuality. A reframing of the traditional narrative of suffrage history can help recover the stories of queer suffragists and their significant role as changemakers in the suffrage movement while illuminating the factors that led to the marginalization of some of these individuals and the erasure of their queerness from the historic record.

I use the term queer throughout this book as an umbrella term to refer to suffragists who were not strictly heterosexual or cisgender. My use of the term queer is not in any way intended to obscure or conflate individual sexual or gender identities but is used to provide a concise way to discuss those suffragists who transgressed norms. This term includes individuals who, if they were alive today, might identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, asexual, aromantic, pansexual, non-binary, gender queer, or gender non-conforming. The language we use changes over time and although these labels are common today, individuals in the past did not use these terms to identify themselves. Sexuality and gender as individual or collective identities were only beginning to emerge at the time under study. Yet, individuals expressing a range of genders and sexualities lived during this era. Queer people always have and always will exist.

In addition to the focus on recovering the lives of queer suffragists, this book also seeks to queer the history of the womens suffrage movement as a whole. The act of queering history allows us to disrupt the traditional framing of a topic and consider it from different perspectives. Scholars have already begun queering the history of the womens suffrage movement by deconstructing the dominant narrative and creating a more nuanced analysis through a discussion of race and class. Queering the suffrage movement can also help us move beyond a framework that privileges a cisheteronormative perspective to consider how suffragists challenged white, middle-class sexual and gender conventions while navigating the complexities of respectability politics.

Dr. Mary Edwards Walker was not always on the fringe of the suffrage movement. In the mid-nineteenth century, Elizabeth Smith Miller and Amelia Bloomer advocated dress reform as a way of freeing women from the physical restrictions imposed by their clothing. The new outfit typically consisted of some sort of pants worn underneath a shortened dress, thus freeing women from heavy petticoats and corsets that constricted their internal organs and damaged womens health. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, and Susan B. Anthony also eagerly adopted bloomers as symbolic of their efforts to liberate women from the larger subjugation they faced in society. However, opponents of womens rights and of dress reform mocked and assaulted women who appeared in public dressed in bloomers, deriding them as mannish women. These insults, combined with pressure from peers who objected to the negative publicity generated by the outfit, eventually forced most womens rights reformers to capitulate and abandon the attire in order to focus solely on the goal of womens suffrage. But others, like Walker, continued to advocate for a radical restructuring of societal gender norms beyond simply winning the vote.

Next page