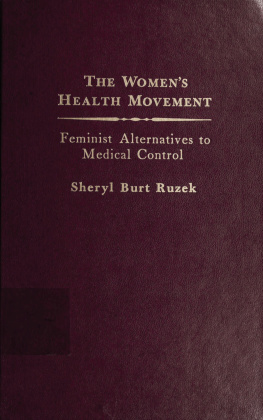

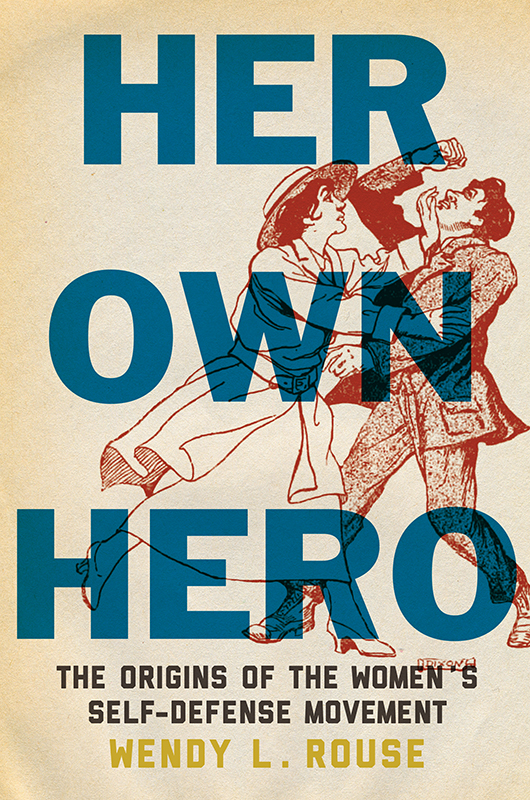

Her Own Hero

Her Own Hero

The Origins of the Womens Self-Defense Movement

Wendy L. Rouse

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2017 by New York University

All rights reserved

An earlier and partial version of the introduction was published (with Beth Slutsky) in the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 13, no. 4 (September 2014): 470499, copyright 2014, Cambridge University Press; reprinted by permission.

An earlier and partial version of chapter 2 was published in the Pacific Historical Review 84, no. 4 (November 2015): 448477; copyright 2015, Pacific Coast Branch, American Historical Association, and the University of California Press; reprinted by permission.

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rouse, Wendy L., author.

Title: Her own hero : the origins of the womens self-defense movement / Wendy L. Rouse.

Description: New York : New York University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017003624 | ISBN 9781479828531 (cloth : alkaline paper)

Subjects: LCSH : Self-defense for womenUnited StatesHistory. | Self-defenseSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory. | WomenUnited StatesSocial conditions. | WomenPolitical activityUnited StatesHistory. | Womens rightsUnited StatesHistory. | FeminismUnited StatesHistory. | Social movementsUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC GV1111.5 .R68 2017 | DDC 613.6/6082dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017003624

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

Contents

This project grew not only from my research and interest in Progressive Era history but also from my personal history in learning and teaching womens self-defense. I began studying martial arts at ten years of age and had the privilege of training under the direction of some amazing teachers. My first instructor, Bart Wilson, instilled in me a sense of confidence and taught me a love of Japanese karate. At Sacramento State University, I continued my training in the martial arts through the study of Okinawan karate with Joan Neide, a professor of kinesiology and teacher of Uechi-ryu. Joan has had a profound influence on so many students over the years, fostering in us all a deep respect for the history of martial arts. She provides an example of excellence in teaching and remains a mentor to her students, past and present. I also wish to thank Uechi-ryu teacher Robert Van Der Volgen, who is also an amazing instructor modeling a patient style of teaching and a dedication to gender equity in the martial arts. I have learned so much over the years from fellow martial artists and advocates of womens self-defense whose commitment to their own training and teaching provided an inspiration for much of this research. Thank you especially to Nikki and Renee Smith for opening my eyes to various approaches to self-defense training by introducing me to the vast networks of women martial artists advocating empowerment models of self-defense through organizations such as Pacific Association of Women Martial Artists (PAWMA).

This book evolved through years of research, paper presentations, and discussions. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to all the individuals who commented on conference presentations, read drafts, provided feedback, and suggested revisions for the various incarnations of this manuscript. I especially want to thank Beth Slutsky, a great colleague and friend who was involved in this project from the beginning. Thank you also to Cecilia Tsu, Jennifer Terry, Sarah Gold McBride, Barbara Molony, Kimberley Jensen, and Renee Laegreid, who commented on initial presentations of this work and helped shape the future direction of my research. Tony Wolf and Emelyne Godfrey were amazing in responding so enthusiastically to my numerous inquiries, tapping into their expertise in the history of womens martial arts around the world. Thank you also to Martha McCaughey, Martha E. Thompson, and Jocelyn Hollander for their insightful research and careful reading and recommendations for the conclusion of this book. Their ongoing scholarship and advocacy on behalf of the empowerment model of womens self-defense are inspirational. I also want to acknowledge my colleagues Maria Alaniz, Wendy Ng, Erica Boas, and Carlos Garcia in the Department of Sociology and Interdisciplinary Social Sciences at San Jose State University for supporting this research. Research grants from the College of Social Sciences helped make this project possible.

Thank you also to the scholars, archivists, and research librarians who helped locate essential resources. I especially want to thank Catherine Palczewski, professor in the Womens and Gender Studies Program at the University of Northern Iowa; Robert Cox at the Department of Special Collections and University Archives at the University of Massachusetts Amherst; Lauren Sodano at the George Eastman Museum in Rochester, New York; Coi E. Drummond-Gehrig at the Denver Public Library; Nyle Monday at the San Jose State University Library; and Kim Stankiewicz of the Polish Genealogical Society of America.

I am also grateful to the individuals who helped edit and improve various chapters of the book in their original form as journal articles, including Alan Lessoff and Jonathan Geffner at the Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and Dave Hedberg, Luke Sprunger, Brenda Frink, Katherine Nelson, and Cathy Valentine at the Pacific Historical Review.

The editorial staff at NYU Press was professional and supportive throughout the publication process. I especially want to thank Clara Platter for believing in this book from the beginning. Thank you also to Amy Klopfenstein for all her assistance along the way. I am grateful to the anonymous readers who gave so freely of their time, offering insightful observations and helping me to reconceptualize the significance of my findings and place them in a much broader context.

Finally, I wish to thank my parents, Sherry Sweeney and Denis and Jennifer Sweeney, for encouraging and supporting me in all aspects of my life. Thank you to the rest of my familyBridget Kearns, Michelle Forrester, Catriona Harris, Amanda Sweeney, Patricia Sweeney, Emily Spece, Lance Spece, and Diane Rousefor doing what family does best in alternately mocking and supporting me. It is good to know we are always there for each other. I am most indebted to Allison Romero for the inspiration, enthusiasm, and joy that she freely shares with the world. I wont remember anything else.

This book is dedicated to my grandmother Lina Rouse, who patiently listened to me talk about the research over the years but was not able to see the final book. She never failed to love us no matter what passions we pursued and she continues to send her love to us all from the other side.

This book examines the emergence and development of a womens self-defense movement during the Progressive Era as women across the nation began studying boxing and jiu-jitsu. The womens self-defense movement arose simultaneously with the rise of the physical culture movement, concerns about the strength and future of the nation, fears associated with immigration and rapid urbanization, and the expansion of womens political and social rights. However, the meaning and transformation wrought through self-defense training varied from individual to individual. Women were inspired to take up self-defense training for very personal reasons that ranged from protecting themselves from stranger attacks on the street to rejecting gendered notions about feminine weakness and empowering themselves. Womens training in boxing and jiu-jitsu was both a reflection of and a response to the larger womens rights movement and the campaign for the vote. Self-defense training also opened up conversations about the less visible violence that many women faced in their own private lives.

Next page