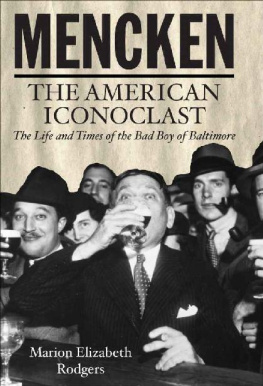

Title: In Defense of Women

Author: H. L. Mencken

Release Date: August 26, 2008 [EBook #1270]

Last Updated: February 6, 2013

Language: English

Produced by Joseph Gallanar, and David Widger

IN DEFENSE OF WOMEN

by H. L. Mencken

CONTENTS

Introduction

As a professional critic of life and letters, my principal business in the world is that of manufacturing platitudes for tomorrow, which is to say, ideas so novel that they will be instantly rejected as insane and outrageous by all right thinking men, and so apposite and sound that they will eventually conquer that instinctive opposition, and force themselves into the traditional wisdom of the race. I hope I need not confess that a large part of my stock in trade consists of platitudes rescued from the cobwebbed shelves of yesterday, with new labels stuck rakishly upon them. This borrowing and refurbishing of shop-worn goods, as a matter of fact, is the invariable habit of traders in ideas, at all times and everywhere. It is not, however, that all the conceivable human notions have been thought out; it is simply, to be quite honest, that the sort of men who volunteer to think out new ones seldom, if ever, have wind enough for a full day's work. The most they can ever accomplish in the way of genuine originality is an occasional brilliant spurt, and half a dozen such spurts, particularly if they come close together and show a certain co-ordination, are enough to make a practitioner celebrated, and even immortal. Nature, indeed, conspires against all such genuine originality, and I have no doubt that God is against it on His heavenly throne, as His vicars and partisans unquestionably are on this earth. The dead hand pushes all of us into intellectual cages; there is in all of us a strange tendency to yield and have done. Thus the impertinent colleague of Aristotle is doubly beset, first by a public opinion that regards his enterprise as subversive and in bad taste, and secondly by an inner weakness that limits his capacity for it, and especially his capacity to throw off the prejudices and superstitions of his race, culture anytime. The cell, said Haeckel, does not act, it reactsand what is the instrument of reflection and speculation save a congeries of cells? At the moment of the contemporary metaphysician's loftiest flight, when he is most gratefully warmed by the feeling that he is far above all the ordinary airlanes and has absolutely novel concept by the tail, he is suddenly pulled up by the discovery that what is entertaining him is simply the ghost of some ancient idea that his school-master forced into him in 1887, or the mouldering corpse of a doctrine that was made official in his country during the late war, or a sort of fermentation-product, to mix the figure, of a banal heresy launched upon him recently by his wife. This is the penalty that the man of intellectual curiosity and vanity pays for his violation of the divine edict that what has been revealed from Sinai shall suffice for him, and for his resistance to the natural process which seeks to reduce him to the respectable level of a patriot and taxpayer.

I was, of course, privy to this difficulty when I planned the present work, and entered upon it with no expectation that I should be able to embellish it with, almost, more than a very small number of hitherto unutilized notions. Moreover, I faced the additional handicap of having an audience of extraordinary antipathy to ideas before me, for I wrote it in war-time, with all foreign markets cut off, and so my only possible customers were Americans. Of their unprecedented dislike for novelty in the domain of the intellect I have often discoursed in the past, and so there is no need to go into the matter again. All I need do here is to recall the fact that, in the United States, alone among the great nations of history, there is a right way to think and a wrong way to think in everythingnot only in theology, or politics, or economics, but in the most trivial matters of everyday life. Thus, in the average American city the citizen who, in the face of an organized public clamour (usually managed by interested parties) for the erection of an equestrian statue of Susan B. Anthony, the apostle of woman suffrage, in front of the chief railway station, or the purchase of a dozen leopards for the municipal zoo, or the dispatch of an invitation to the Structural Iron Workers' Union to hold its next annual convention in the town Symphony Hallthe citizen who, for any logical reason, opposes such a proposalon the ground, say, that Miss Anthony never mounted a horse in her life, or that a dozen leopards would be less useful than a gallows to hang the City Council, or that the Structural Iron Workers would spit all over the floor of Symphony Hall and knock down the busts of Bach, Beethoven and Brahmsthis citizen is commonly denounced as an anarchist and a public enemy. It is not only erroneous to think thus; it has come to be immoral. And many other planes, high and low. For an American to question any of the articles of fundamental faith cherished by the majority is for him to run grave risks of social disaster. The old English offence of "imagining the King's death" has been formally revived by the American courts, and hundreds of men and women are in jail for committing it, and it has been so enormously extended that, in some parts of the country at least, it now embraces such remote acts as believing that the negroes should have equality before the law, and speaking the language of countries recently at war with the Republic, and conveying to a private friend a formula for making synthetic gin. All such toyings with illicit ideas are construed as attentats against democracy, which, in a sense, perhaps they are. For democracy is grounded upon so childish a complex of fallacies that they must be protected by a rigid system of taboos, else even half-wits would argue it to pieces. Its first concern must thus be to penalize the free play of ideas. In the United States this is not only its first concern, but also its last concern. No other enterprise, not even the trade in public offices and contracts, occupies the rulers of the land so steadily, or makes heavier demands upon their ingenuity and their patriotic passion.

Familiar with the risks flowing out of itand having just had to change the plates of my "Book of Prefaces," a book of purely literary criticism, wholly without political purpose or significance, in order to get it through the mails, I determined to make this brochure upon the woman question extremely pianissimo in tone, and to avoid burdening it with any ideas of an unfamiliar, and hence illegal nature. So deciding, I presently added a bravura touch: the unquenchable vanity of the intellectual snob asserting itself over all prudence. That is to say, I laid down the rule that no idea should go into the book that was not already so obvious that it had been embodied in the proverbial philosophy, or folk-wisdom, of some civilized nation, including the Chinese. To this rule I remained faithful throughout. In its original form, as published in 1918, the book was actually just such a pastiche of proverbs, many of them English, and hence familiar even to Congressmen, newspaper editors and other such illiterates. It was not always easy to hold to this program; over and over again I was tempted to insert notions that seemed to have escaped the peasants of Europe and Asia. But in the end, at some cost to the form of the work, I managed to get through it without compromise, and so it was put into type. There is no need to add that my ideational abstinence went unrecognized and unrewarded. In fact, not a single American reviewer noticed it, and most of them slated the book violently as a mass of heresies and contumacies, a deliberate attack upon all the known and revered truths about the woman question, a headlong assault upon the national decencies. In the South, where the suspicion of ideas goes to extraordinary lengths, even for the United States, some of the newspapers actually denounced the book as German propaganda, designed to break down American morale, and called upon the Department of Justice to proceed against me for the crime known to American law as "criminal anarchy," i.e., "imagining the King's death." Why the Comstocks did not forbid it the mails as lewd and lascivious I have never been able to determine. Certainly, they received many complaints about it. I myself, in fact, caused a number of these complaints to be lodged, in the hope that the resultant buffooneries would give me entertainment in those dull days of war, with all intellectual activities adjourned, and maybe promote the sale of the book. But the Comstocks were pursuing larger fish, and so left me to the righteous indignation of right-thinking reviewers, especially the suffragists. Their concern, after all, is not with books that are denounced; what they concentrate their moral passion on is the book that is praised.