H. L. Mencken

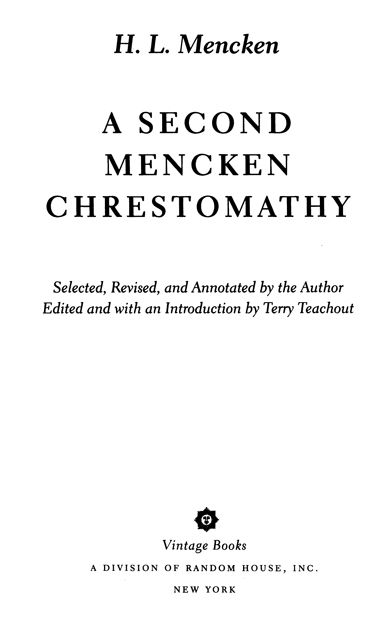

A SECOND

MENCKEN

CHRESTOMATHY

Henry Louis Mencken was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1880 and died there in 1956. A son of August and Anna (Abhau) Mencken, he was educated privately and at Baltimore Polytechnic. In 1930 he married Sara Powell Haardt, who died in 1935. Mencken began his long career as journalist, critic, and philologist as a reporter for the Baltimore Morning Herald in 1899. In 1906 he joined the staff of the Baltimore Sun, thus initiating an association with the Sunpapers that would last until a few years before his death. He was coeditor of the Smart Set with George Jean Nathan from 1914 to 1923, and with Nathan he founded the American Mercury, of which he was sole editor from 1925 to 1933.

ALSO BY H. L. MENCKEN

The American Language

The American Language: Supplement I

The American Language: Supplement II

In Defense of Women

Prejudices

Notes on Democracy

Treatise on the Gods

Treatise on Right and Wrong

Happy Days

Newspaper Days

Heathen Days

A New Dictionary of Quotations

Christmas Story

A Mencken Chrestomathy

Minority Report: H. L. Menckens Notebooks

The Bathtub Hoax

Letters of H. L. Mencken

H. L. Mencken on Music

The American Language: The Fourth Edition and the Two Supplements, Abridged

The American Scene

The Diary of H. L. Mencken

My Life as Author and Editor

FIRST VINTAGE BOOKS EDITION, OCTOBER 1995

Copyright 1994 by Enoch Pratt Free Library

Editing and annotations copyright by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Introduction copyright 1994 by Terry Teachout

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1995.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Mencken, H. L. (Henry Louis), 18801956.

A second Mencken chrestomathy / by H. L. Mencken; selected,

revised, and annotated by the author; edited and with an

introduction by Terry Teachout.1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-83111-8

I. Teachout, Terry. II. Title.

PS3525.E43A6 1994

818.5209dc20

94-12087

v3.1

Contents

EDITORS INTRODUCTION

I HAVE discovered something, Alfred Knopf said to H. L. Mencken one day in 1920. It is that H. L. Mencken has become a good property. Knopf was talking about the unexpected popular success of Prejudices: First Series, the first of six collections of Menckens essays, articles and reviews to appear under the Borzoi imprint between 1919 and 1927. In 1919 Mencken was still known outside Baltimorehis lifelong home and base of operationsmainly as coeditor of and book reviewer for the Smart Set, a shabby-looking magazine of modest circulation and raffish reputation. Prejudices: First Series was intended to bring his writing, and his personality, to the notice of a wider audience: I made a deliberate effort to lay as many quacks as possible, and chose my targets, not only from the great names of the past, but also from the current company of favorites. The effort, like most of Menckens exercises in self-promotion, paid off. Prejudices: First Series and its successors were all reviewed widely and, to the initial surprise of author and publisher alike, even sold well. It was through these neat little crown octavo volumes as much as through the Smart Set (and, later, the American Mercury) that American readers of the 20s came to know the man whom Walter Lippmann, writing in 1926, called the most powerful personal influence on this whole generation of educated people.

In the 30s, Mencken fell from grace with Depression-era intellectuals, who found his literary tastes bourgeois and his politics neanderthal. (Nearly all poverty is caused by idealism. The normal poor man is simply a semi-idiot whose dreams have run away with his capacities.) Prejudices: First Series sold only three-hundred-odd copies between 1931, when the plates were melted down, and 1942, when the last printing was exhausted. But he became a good property again with the publication in 1940 of Happy Days, his best-selling childhood memoir, and it was doubtless no coincidence that around this time he began thinking of putting together a comprehensive anthology of his own writings. As early as 1943, Mencken discussed with Knopf the possibility of bringing out a sort of Mencken Encyclopedia, made up of extracts from my writings over many years, arranged by subject and probably with additions. According to his diary, he went to work in earnest four years later: Unable to do any writing, I have put in my time selecting and editing material for the Mencken Omnibus that Knopf proposes to get out. I am not reading all my old stuff, but I am trying to look through it.

The book that emerged from this lengthy period of gestation was a kind of super-Prejudices, a jumbo volume containing Menckens thoughts on everything from the music of Johann Sebastian Bach (good) to the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (bad). Like the six Prejudices, it was assembled with loving care:

I have got out a lot of stuff from the first four Prejudices books, and some from my early Smart Set book reviews. I have also dug out a lot from magazine and newspaper files, never before printed in books. Some of it, not read for years, strikes me as pretty fair. Most of it has needed a good deal of revision. It was full of references to the affairs of the time, some of them now almost unintelligible. But after cleaning them out, I find myself with [a] good deal of printable stuff. I shall pile it up without plan, and then make my selections. Mrs. Lohrfinck [Rosalind Lohrfinck, Menckens secretary] has already copied 300,000 or 400,000 words, and Ill probably have 1,000,000 before I settle down to make my selections.

By mid-September of 1948, Mencken had blue-penciled this mountain of typescript down to a 265,000-word draft. Knopf hated the proposed title, A Mencken Chrestomathy (according to Mencken, the word means a collection of choice passages from an author or authors), but Mencken insisted on it, going so far as to discreetly twit his old friend in the preface: Nor do I see why I should be deterred by the fact that, when this book was announced, a few newspaper smarties protested that the word would be unfamiliar to many readers, as it was to them. Thousands of excellent nouns, verbs and adjectives that have stood in every decent dictionary for years are still unfamiliar to such ignoramuses, and I do not solicit their patronage. Let them continue to recreate themselves with whodunits, and leave my vocabulary and me to my own customers, who have all been to school. Not surprisingly, the ever-practical Mencken was more responsive to Knopfs concerns about the length of the first draft: I myself feel that there are things in the present text that had better come out, so we should be able to reach an agreement without difficulty. There is an excess of copied material about equal in bulk to the matter now in the book. Thus, if the Chrestomathy has an encouraging sale Ill be ready to produce a second volume.

Mencken delivered a 185,000-word revised draft on September 24, 1948, and approved the copyedited manuscript on November 8. Fifteen days later, a massive stroke left him unable to read or write for the rest of his life.