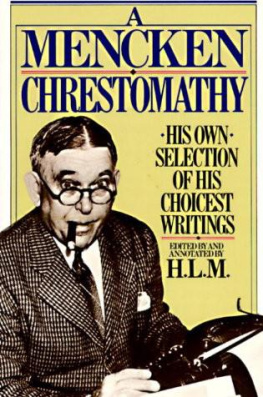

Mr. Mencken has also written

THE AMERICAN LANGUAGE

PREJUDICES: SIX SERIES

SELECTED PREJUDICES

A BOOK OF BURLESQUES

A BOOK OF PREFACES

IN DEFENSE OF WOMEN

NOTES ON DEMOCRACY

TREATISE ON THE GODS

TREATISE ON RIGHT AND WRONG

he has translated

THE ANTICHRIST

by F. W. Nietzsche

he has written introductions to

VENTURES IN COMMON SENSE

by E. W. Howe

MAJOR CONFLICTS

by Stephen Crane

THE AMERICAN DEMOCRAT

by James Fenimore Cooper

CANCER: WHAT EVERYONE

SHOULD KNOW ABOUT IT

by James Tobey

These are BORZOI BOOKS published by

Alfred A. Knopf

OCTOBER 8 1888

Copyright 1939, 1940 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper.

Published simultaneously in Canada by

The Ryerson Press

eISBN: 978-0-307-83087-6

v3.1

Some of these chapters have appeared, either wholly or in part, in the New Yorker. The author offers his thanks to the editors of that magazine for permission to reprint them.

Preface

T HESE casual and somewhat chaotic memoirs of days long past are not offered to the nobility and gentry as coldly objective history. They are, on the contrary, excessively subjective, and the record of an event is no doubt often bedizened and adulterated by my response to it. I have made a reasonably honest effort to stick to the cardinal facts, however disgraceful to either the quick or the dead, but no one is better aware than I am of the fallibility of human recollection. Fortunately, I have been able to resort, at many points, to contemporary inscriptions, for my people have lived in one house in Baltimore since 1883, and when I returned to it in 1936, after five years of absence, and began to explore it systematically, I found its cupboards and odd corners full of family memorabilia. My mother, who died in 1925, was one of those old-fashioned housewives who never threw anything away, and in the years following her death my sister apparently made only slow progress in excavating and carting off her interminable accumulations. Moreover, I found that my father, ordinarily no cherisher of archives, had nevertheless preserved, for some reason unknown, a file of household bills running from the year of his marriage to the early nineties not a complete file, by any means, but still one showing many well-chosen and instructive specimens.

I have mined this file diligently, and found a number of surprises in it. One is the discovery that my memory was grossly at fault, for nearly half a century, on a salient point of my education. For all those years I boasted that I could read music at the age of six at the latest indeed, I boasted that I could read it so far back in my nonage that it was impossible for me to recall the time when I couldnt. These boasts turned out, on reference to the bill file, to be mere sound and hooey, signifying nothing. Therein, as plain as day, was a receipt showing beyond cavil that there was no piano in the house until my eighth year or, to be precise, until I was seven years, four months and one day old. This disconcerting experience caused me to check and re-check the whole saga of my infant recollections, partly by the same bill file, partly by the countless other documents, glyphs and cave-drawings in the house, and partly by the memories of surviving contemporaries. I unearthed many other errors, but none so gross as the one about my genesis as a Tonknstler, and on the whole I made a pretty good average score. As Huck Finn said of Tom Sawyer, there are no doubt some stretchers in this book, but mainly it is fact.

It has, so far as I can make out, no psychological, sociological or politico-economic significance. My early life was placid, secure, uneventful and happy. I remember, of course, some griefs and alarms, but they were all trivial, and vanished quickly. There was never an instant in my childhood when I doubted my fathers capacity to resolve any difficulty that menaced me, or to beat off any danger. He was always the center of his small world, and in my eyes a man of illimitable puissance and resourcefulness. If we needed anything he got it forthwith, and usually he threw in something that we didnt really need, but only wanted. I never heard of him being ill-treated by a wicked sweat shop owner, or underpaid, or pursued by rent-collectors, or exploited by the Interests, or badgered by the police. My mother, like any normal woman, formulated a large programme of desirable improvements in him, and not infrequently labored it at the family hearth, but on the whole their marriage, which had been a love match, was a marked and durable success, and neither of them ever neglected for an instant their duties to their children. We were encapsulated in affection, and kept fat, saucy and contented. Thus I got through my nonage without acquiring an inferiority complex, and the present chronicle, both in its materials and in its point of view, must needs fall out of the current fashion, which seems to favor tales of dirty tenements, wage cuts, lay-offs, lockouts, voracious landlords, mine police, foreclosed mortgages, evictions, rickets, prostitution, larceny, grafting cops, anti-Semitism, Bryanism, Hell-fire, droughts, xenophobia, and other such horrors. I was a larva of the comfortable and complacent bourgeoisie, though I was quite unaware of the fact until I was along in my teens, and had begun to read indignant books. To belong to that great order of mankind is vaguely discreditable today, but I still maintain my dues-paying membership in it, and continue to believe that it was and is authentically human, and therefore worthy of the attention of philosophers, at least to the extent that the Mayans, Hittites, Kallikuks and so on are worthy of it.

How, on one of its levels, it lived and had its being in a great American city in the penultimate decade of the last century is my theme, in so far as there is any theme here at all. I shut down my narrative with the year 1892, which saw my twelfth birthday. I was then at the brink of the terrible teens, and existence began inevitably to take on a new and more sinister aspect. It may be that Ill resume the story later on, but that is not certain, for on the whole I am more interested in what is going on now than in what befell me (or anyone else) in the past. My days of work have been mainly spent, in fact, in recording the current scene, usually in a far from acquiescent spirit. But I must confess, with sixty only around the corner, that I have found existence on this meanest of planets extremely amusing, and, taking one day with another, perfectly satisfactory. If I had my life to live over again I dont think Id change it in any particular of the slightest consequence. Id choose the same parents, the same birthplace, the same education (with maybe a few improvements here, chiefly in the direction of foreign languages), the same trade, the same jobs, the same income, the same politics, the same metaphysic, the same wife, the same friends, and (even though it may sound like a mere effort to shock humanity), the same relatives to the last known degree of consanguinity, including those in-law. The Gaseous Vertebrata who own, operate and afflict the universe have treated me with excessive politeness, and when I mount the gallows at last I may well say with the Psalmist (putting it, of course, into the prudent past tense): The lines have fallen unto me in pleasant places.