Articles originally published in The Baltimore Sun are 1925 and reprinted with the permission of the The Baltimore Sun. Permission also granted by Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore, in accordance with the terms of the bequest of H.L. Mencken. In Tennessee is reprinted from the July 1, 1925, issue of The Nation. Permission also granted by Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore, in accordance with the terms of the bequest of H.L. Mencken. Permission to reprint To Expose a Fool from The American Mercury, October 1925, is granted by Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore, in accordance with the terms of the bequest of H.L. Mencken.

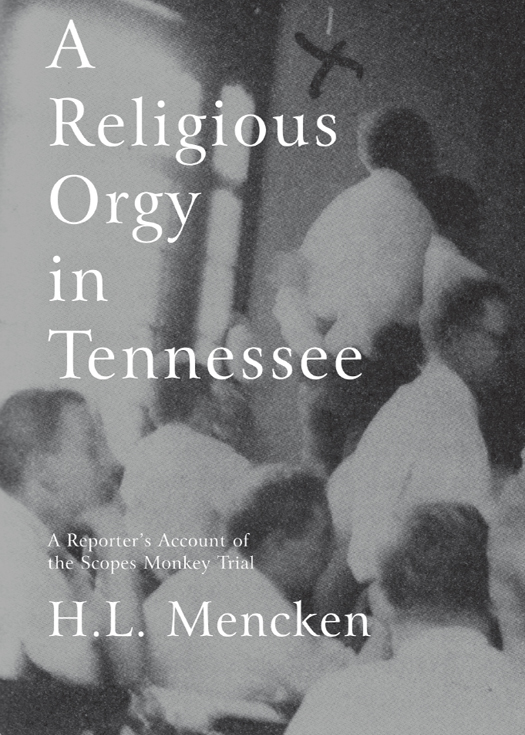

Cover photo shows H.L. Mencken (upper right with hands clasped behind his back) standing on a table to look over the crowd at the proceedings at the Rhea County Courthouse. This photograph is courtesy of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, H.L. Mencken Collection.

Special acknowledgement is made to Averil Kadis, of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, and Tom Davis, of Bryan College, for assistance with research and permissions.

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, New York 11201

The Library of Congress has cataloged the paperback edition as follows:

Mencken, H. L. (Henry Louis), 1880-1956.

A religious orgy in Tennessee : a reporters account of the Scopes monkey trial / H.L. Mencken. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Articles originally published in The Baltimore Sun, The Nation, or The American Mercury.

eISBN: 978-1-61219-031-0

1. Scopes, John ThomasTrials, litigation, etc.Press coverageMarylandBaltimore. 2. EvolutionStudy and teachingLaw and legislationTennessee. 3. Mencken, H. L. (Henry Louis), 1880-1956Political and social views. I. Title.

KF224.S3M46 2006

345.730288dc22

2006022870

v3.1

IV: Mencken Finds Daytonians Full of

Sickening Doubts About Value of Publicity

V: Impossibility of Obtaining Fair Jury

Insures Scopes Conviction, Says Mencken

VI: Mencken Likens Trial to a Religious Orgy,

with Defendant a Beelzebub

VII: Yearning Mountaineers Souls Need

Reconversion Nightly, Mencken Finds

VIII: Darrows Eloquent Appeal Wasted on Ears

That Heed Only Bryan, Says Mencken

IX: Law and Freedom, Mencken Discovers,

Yield Place to Holy Writ in Rhea County

X: Mencken Declares Strictly Fair Trial Is

Beyond Ken of Tennessee Fundamentalists

XI: Malone the Victor, Even Though Court

Sides with Opponents, Says Mencken

XII: Battle Now Over, Mencken Sees;

Genesis Triumphant and Ready for New Jousts

Introduction

By Art Winslow

We have the stage antics of baseball-player-turned-evangelist William Ashley SundayBilly Sundayand the weak ankles of the Tennessee General Assembly to thank for the high theater of the Scopes Trial of 1925. As recounted by Edward J. Larson in his excellent Evolution: The Remarkable History of a Scientific Theory, the state senate, considering a ban on the teaching of evolution in public schools, had already rejected the idea in committee when Billy Sunday swept into Memphis for an eighteen-day revival that February.

Long before Elvis was to earn fame with his gyrations, this gymnast for Jesus, Larson tells us, jumped, kicked and slid across the stage while denouncing the tommyrot of evolution, the possibility that we came from protoplasm, instead of being born of God Almighty. When the legislators noticed that Sundays sermons had drawn an aggregate audience of some 200,000 constituents, the senate committee reversed itself, leading to passage of the Butler Act, signed into law in March by Governor Austin Peay virtually unchanged from the wording crafted by its author, a farmer named John Washington Butler.

It shall be unlawful for any teacher in any of the universities, Normals and all other public schools of the State which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals, the Butler Act stipulated. To transgress it was a misdemeanor, punishable by a minimum fine of $100 and a maximum of $500 for each offense.

Tennessee was not the only state in which sentiment against Darwins ideas soaked enough ground to seep into public policy. Two years before, in 1923, Oklahoma had banned textbooks that promoted Darwinism, and in 1924 California required teachers to approach evolution as a theory only. Kansas was a seedbed for anti-evolution activists as well, including the lecturer Charles L. Clayton, who tried to blur the boundaries between science and religion by asserting an intelligent force, a Doctrine of Design, which can be seen as the forebear of modern-day belief in Intelligent Design.

One of the preeminent leaders of the anti-Darwin movement at the time was William Jennings Bryan, a three-time presidential candidate, two-time Nebraska Congressman and onetime Secretary of State for Woodrow Wilson. Known as the Great Commoner, Bryans 1922 book In His Image made clear his feelings on the subject of evolution:

While survival of the fittest may seem plausible when applied to individuals of the same species, it affords no explanation whatever, of the almost infinite number of creatures that have come under mans observation. To believe that natural selection, sexual selection or any other kind of selection can account for the countless differences we see about us requires more faith in chance that a Christian is required to have in God.

* * *

The Bible does not say that reproduction shall be nearly according to kind or seemingly according to kind. The statement is positive that it is according to kind, and that does not leave room for the changes however gradual or imperceptible that are necessary to support the evolutionary hypothesis.

Bryan also wrote, If we accept the Bible as true we have no difficulty in determining the origin of man, and that Darwinian doctrine has been the means of shaking the faith of millions, is absurd and harmful to society, and further, it attacks the very foundations of Christianity. Darwinism offers no reason for existence and presents no philosophy of life; the Bible explains why man is here and gives us a code of morals that fits into every human need, Bryan observed.

Bryans involvement in the Scopes trial had an air of preordainment about it, for the proceeding itself smacked of intentionality from the outset. In early May 1925, the fledgling American Civil Liberties Union publicized its eagerness to find a test case against the newly minted Butler Act by offering to defend any teacher accused under it. George Rappelyea, a manager for the Cumberland Coal and Iron company in Dayton, Tennessee, saw notice of that in the Chattanooga Daily Times and, sensing opportunity, brought it to the attention of Frank Earle Robinson, proprietor of a local drug store but also chair of the Rhea County School Board. Before another day had elapsed, a meeting was arranged that included Rappelyea, Robinson, school superintendent Walter White, a pair of the citys lawyers (Sue Hicks and his brother Herbert Hicks, who went on to work for the prosecution), and John Scopes, an athletic coach and substitute teacher who agreed to be the defendant to test the law. Scopes was not the schools designated biology teacher, but he had filled in and perhaps even taught evolution in a way that contravened the law (the defense did not contest the matter at trial).