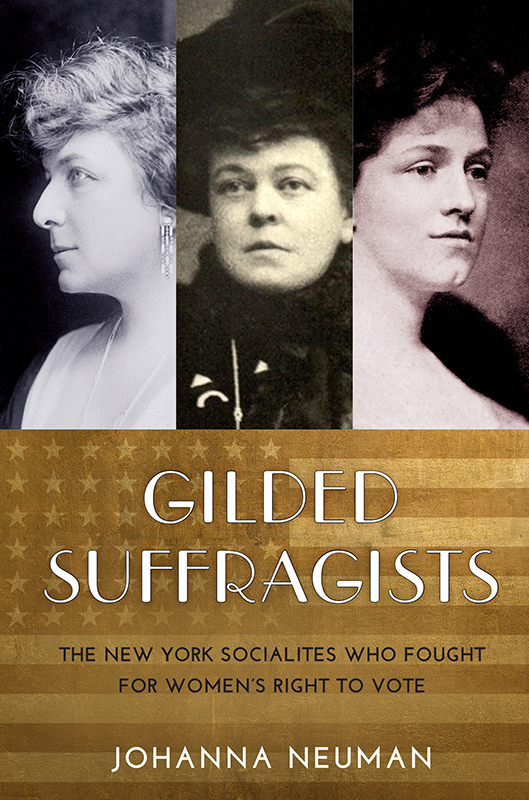

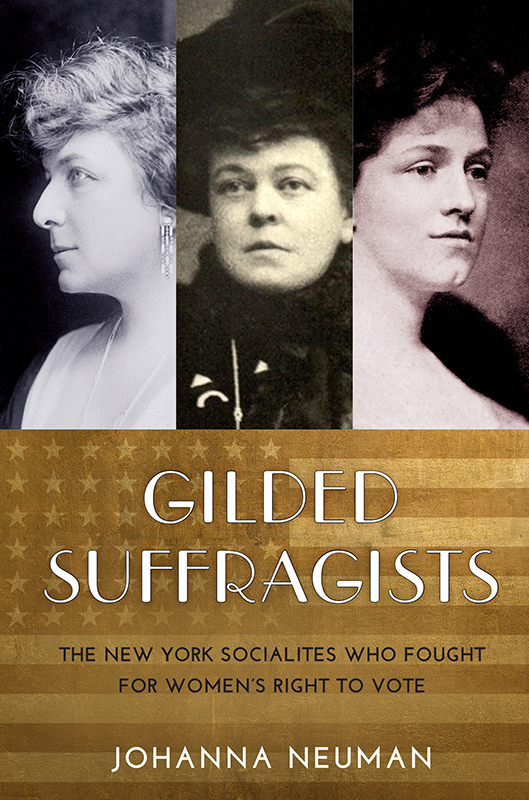

Gilded Suffragists

Gilded Suffragists

The New York Socialites Who Fought for Womens Right to Vote

Johanna Neuman

WASHINGTON MEWS BOOKS

An Imprint of

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

WASHINGTON MEWS BOOKS

An imprint of

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2017 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ISBN : 978-1-4798-3706-9

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data, please contact the Library of Congress.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

To the memory of E VELYN and S EYMOUR N EUMAN,

who nurtured the child

To H ILDIE N EUMAN L YDDAN and W ILLIAM C. L YDDAN ,

who nurtured the idea

And to J EFFREY G LAZER ,

who nurtures the woman

Contents

The illustrations appear as a group before Chapter 6.

I N every successful movement for social change there is a moment when the generations cross paths, when an idea once deemed radical loses its toxins, now familiar rather than frightful, assumed rather than threatening. In the campaign by women to win the right to vote in America, that moment came in 1908, when an unlikely band of wealthy socialites better known for the excesses of their Fifth Avenue balls and the Beaux Arts luxury of their Newport mansions helped reignite a claim for citizenship. Not since Elizabeth Cady Stanton first advocated a womans right to vote at the 1848 Womans Rights Convention at Seneca Falls had the debate over the female franchise so energized the national political landscape. Leveraging their social standing for political gain, these gilded suffragists normalized the idea that women of all stripesnot just those of the intellectual circle who had originated the ideawanted the vote. No one was more astonished than the newspaper reporters who covered them. It was as if, said one scribe, their infusion of celebrity had taken the campaign from dowdy to fashionable.

At a time when the newspaper industry was at its zenithNew York at the turn of the century boasted twenty-nine daily papers obsessed with the doings of society these fashion-plated activists became players in the vibrant media landscape, no doubt reassuring men that they could vote for suffrage without losing their masculinity and calming women who feared that the ballot would make them unwomanly. Joining one of the broadest coalitions for social change in U.S. history, one that combined under its tent the poorest immigrant with the wealthiest socialite, the angry radical and the mild-mannered progressive, they gave the movement a sense of moment.

In their motives, they were hardly monolithic. Their inspiration ran the gamut from progressive ideals of good governance to unabashed efforts to protect their class privilege. Some joined Heterodoxy, a womens club based in Greenwich Village that held weekly debates over such heretical topics as free love, socialism, and racial tolerance. Others balked at marching in the suffrage parades along Fifth Avenue for fear it would mark them as ladies of the night. Some went to jail for protesting in front of Woodrow Wilsons White House, choosing prison rather than paying a modest fine. Others distanced themselves from Britains Emmeline Pankhurst, ducking the specter of militancy and violence.

What connected them was a sense of great social change. It was a time when a new century beckoned and bohemian critics in Greenwich Village were challenging every institution from capitalism to marriage, experimenting with socialism, free love, art, and birth control. For women of the gilded set, modernity meant jettisoning old social customsthe cotillion and the costumed ball, the layers of clothes and rigidity of table settings, the decorous courtship and the marriage of strangersin favor of education, career, and independence. If they had remained on the sidelines, they would have become anachronisms, the fate of those who clung to their status as wives and daughters of Americas most infamous capitalists, just as the Jazz Age was making celebrities of sports figures, musicians, and radio actors. Instead they made a bid for influencenot the moral suasion of motherhood or the indirect power of social standing, but the political influence of the men of their class, long denied them because of their gender.

Some contemporaries dismissed their participation as a fad, the indulgence of bored socialites trying on suffrage as they might the latest couture designs from Paris.

In newspaper accounts of the day, their names were hidden behind the moniker of Mrs. Somebody Else. Excavating their identities and biographies was a work of archaeology, the sense of discovery bolstered as their numbers grew to more than two hundred. Researching their religious and political affiliations, their club memberships and civic causes, the source of their wealth and the generation they were born intoall provided stunning examples of how a new century had shifted the ground beneath their feet. By 1920, more than a tenth of the gilded suffragists had divorced, quite a few had ridden bicycles or attended a university, and many had become published authors, baring their souls in scandalous candor.

Comfortable with the power that wealth conferred, these women treated politics as an extension of their realm as social figures. Accustomed to running large estates, they knew how to prod and when to delegate. Conditioned to press sensationalism, they knew how to manage the media. With large budgets and a taste for luxury, they also reveled

The results of their intervention were consequentialand instructive. From the celebrity capital of New York, they joined a cause that had been in the doldrums and made it seem intoxicating to a nationwide public. Newspaper coverage surged, attendance at suffrage events swelled, and the campaign gained ground. In their footprints, they also left a roadmap of how social change is made in Americasometimes by defusing radicalism, other times by breaching political decorum, always by appealing to a public that in the case of womens suffrage had proved indifferent to the cause for more than fifty years. As one activist wrote to a friend who had been traveling in Asia, Its now fashionable among the actresses to be a suffragetteEthel Barrymore has come out for it and Beatrice Forbes Robertson has even abandoned the stage to lecture upon it. Oh, God, its so good.

A Club of Their Own

In New York Society, the older families never allow the turmoil of outside life to enter their social scheme.

Henry Cabot Lodge

C LAD in his gold-laced uniform, the watchman on duty at the Spouting Rock Beach Association knew by sight every carriage in Newport, Rhode Island. Only the elite could pass through his gates to sunbathe at Baileys Beach, a stretch of sand claimed by the wealthy in 1890 after trolley service made an earlier and more desirable plot, Easton Beach,

Next page