2020 Neylan McBaine

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, Shadow Mountain, at permissions@shadowmountain.com. The views expressed herein are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the position of Shadow Mountain.

Portions of this book are historical fiction. Characters and events in this book are represented fictitiously.

Visit us at shadowmountain.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: McBaine, Neylan, author.

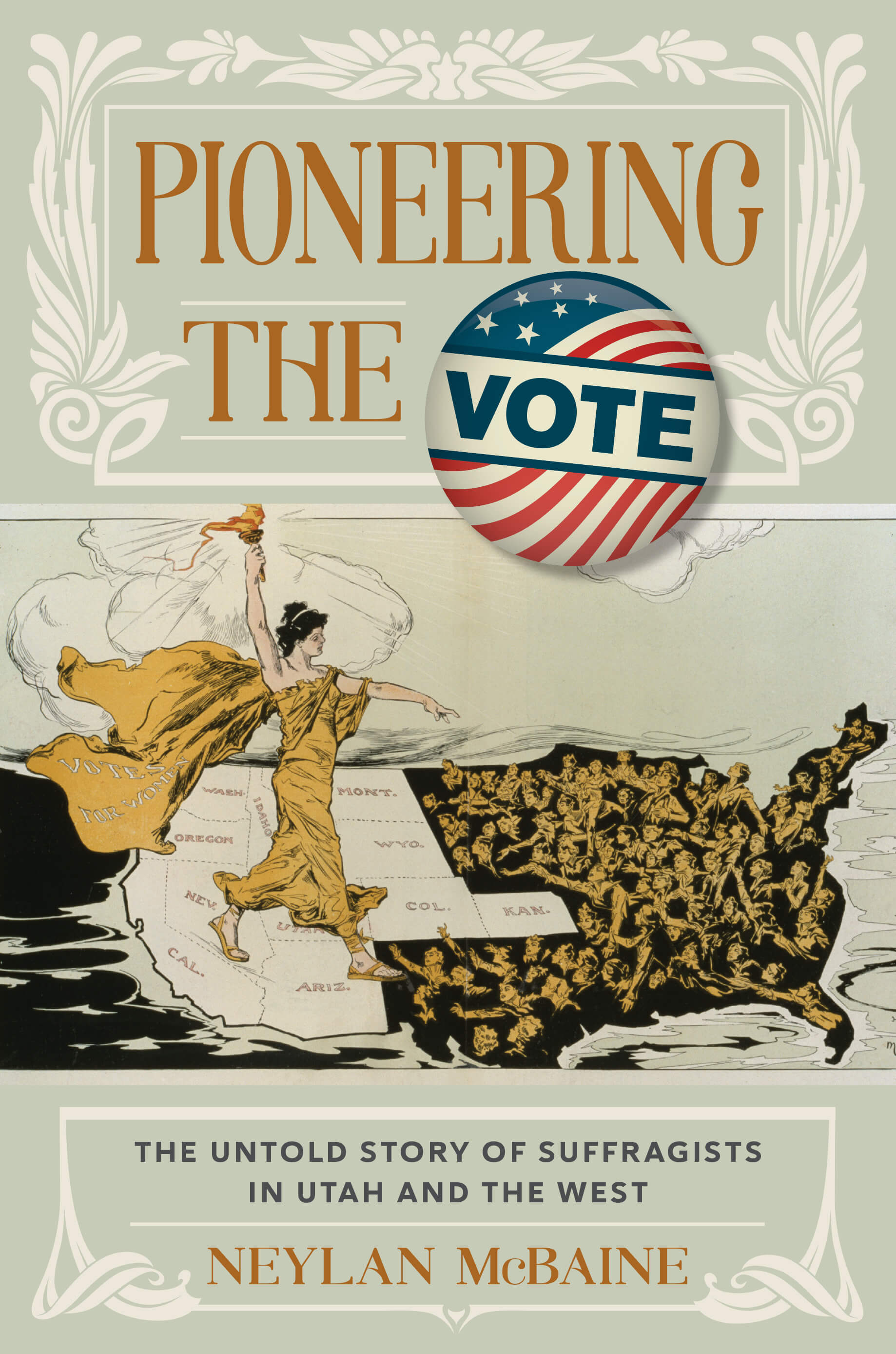

Title: Pioneering the vote : the untold story of suffragists in Utah and the West / Neylan McBaine.

Description: Salt Lake City : Shadow Mountain, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references. | Summary: A history of the suffragist movement among the pioneers who settled the West, in particular members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day SaintsProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020009532 | ISBN 9781629727363 (hardback) | eISBN 978-1-62973-889-5 (eBook)

Subjects: LCSH: Wells, Emmeline B. (Emmeline Blanche), 18281921Fiction. | WomenSuffrageUtahHistory. | WomenSuffragePacific and Mountain StatesHistory. | SuffragistsUtahBiography. | SuffragistsPacific and Mountain StatesBiography. | Mormon womenUtahBiography. | Mormon womenPacific and Mountain StatesBiography. | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC JK1911.U8 M33 2020 | DDC 324.6/230978dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020009532

Printed in the United States of America

Lake Book Manufacturing, Inc., Melrose Park, IL

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cover Illustration: The Awakening , by Henry Mayer

1915 Library of Congress LC-DIG-ds-1236.

Vote pin Shutterstock/ bearsky23

Decorative border Shutterstock/bomg

Book design: Shadow Mountain

Art direction: Richard Erickson

Design: Sheryl Dickert Smith

For Elliot, who is dedicated to all of the thinking women in his life.

The story of the struggle for womans suffrage in Utah is the story of all efforts for the advancement and betterment of humanity, and which has been told over and over since the advent of civilization.

Dr. Martha Hughes Cannon,

first female state senator in Utah

and the United States

Most womens suffrage and

feminist historians have almost entirely ignored the West.

Sandra L. Myres ,

historian

Contents

Preface

O n August 26, 2020, we celebrate the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, the constitutional amendment that extended voting rights to American women. There are currently several museum exhibits in Washington, D.C., honoring the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment and the suffrage movement that led to its passage. There are newspaper editorials, important new books, documentaries, and celebratory events. But almost all of these fail to seriously consider the role of the western states and territories in delivering suffrage triumphs up to fifty years before the amendment. And none honor the fact that this year, on February 14, we also marked the 150th anniversary of the first female vote under an equal suffrage law, which happened in the unlikeliest of places: Utah.

On February 14, 1870, Salt Lake City resident and twenty-three-year-old schoolteacher Seraph Young was the first American woman to cast a ballot with suffrage rights equal to mens. Two days earlier, the Utah Territorial Legislature had granted women the right to vote in all elections, and Utah women went to the polls to exercise their new right in a municipal election that very week. Wyoming, Colorado, and Idaho also were home to trailblazing men and women in the fight to recognize womens right to contribute politically. In fact, by the time the Nineteenth Amendment extended womens voting rights across the nation, all of the states that had already granted full suffrage to their women were in the West. Glaringly, the first thirty states to join the Union were the last to grant full suffrage rights.

There has been extremely little scholarship examining why such a radical movement as granting women political voices found its first triumphs in the western states and territories. As historian Sandra L. Myres notes, Most womens suffrage and feminist historians have almost entirely ignored the West. Writers have concentrated on the national suffrage leaders and on the history of the movement in the eastern states. Western suffrage votes are treated as some sort of aberrant political behavior rather than as part of the mainstream suffrage movement.

Some historians explain the Wests behavior by noting the spirit of innovation that was both common and necessary in the frontier West. To survive and thrive, frontier dwellers had to put aside the expectations and traditions of their Eastern counterparts. While it is true that the relationship between the frontier experience and the womens movement is important, this theory oversimplifies the motivations and political forces driving the first suffrage triumphs.

This book proposes that one reason the suffrage leadership of Utah, Wyoming, Colorado, and Idaho is not more fully explored is because the forces that drove the movement in those areas are now uncomfortable and even foreign to contemporary audiences. Each of the first four suffrage wins was the result of specific local pressures that have little resonance in our modern world. For example, the fight for the vote in Utah was inextricably intertwined with the fight over polygamy, the practice of a man taking more than one wife. The federal government demanded its extinction, while the Utahns demanded both freedom of religion and the right to govern themselves. The women of Utah, the vast majority of whom were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and some of whom were in plural marriages, sought the vote to prove they were independent, unoppressed, and intelligent agents of their own wills. But the specter of polygamy overrode any voice that might have carried their message down through history.

Wyoming, Colorado, and Idaho each had their own forces at work as well, and some, such as racism and the movement to ban alcohol, are also hard for us to unpack today. In contrast, the suffrage movement of the twentieth centuryfrom 1910 to the amendments passage in 1920captures our imagination much more easily. We feel kinship with the moral rightness that we see in the last decade of the fight: women should participate in our civic governance because it is right , because women are people too. We are captivated by the mass media images that arose from the new centurys consumer culture and the advent of modern advertising. We see in the clever slogans the birth of our own media landscape. We recognize our own brand of activism: the marches, the banners, the hunger strikes. We see reverberations even today of women chaining themselves to the White House fence, of the rage boiling just beneath the surface as we participate in annual womens marches.