First published in the United States of America by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2018

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA IS AVAILABLE.

pp. : Courtesy of the Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music, The Sheridan Libraries, The Johns Hopkins University

To todays suffragists, Hannah Auerbach, Sara Weiss, and Ariel and Noam Hasak-Lowy.

May your dreams come true as you conquer the world.

And to our new addition to the suffragist collective, Lily Auerbach.

May the ERA be passed and all your rights protected as you conquer the world.

CHAPTER

1

Enough of the Everlasting No

The story of a womans right to vote in the United States actually begins in England. And not at an event about womens rights at all, but at an antislavery convention instead. This story begins with a humiliating no, and with a pivotal friendship born out of this shared, stinging, and all-too-familiar disappointment.

The World Anti-Slavery Convention of 1840 gathered in London on June 12, an unusually bright and sunny day. One month earlier on May 11, twenty-four-year-old Elizabeth Cady Stanton had boarded a ship called the Montreal with her new husband, Henry Stanton, to make the three-thousand-mile trip from New York to England, which would last eighteen days. Henry was a full-time abolitionista powerful speaker and leader in the American movement to end slaveryas well as a delegate to this convention.

Young Elizabeth was not a delegate and was still somewhat new to the abolitionist movement and its ideas. But she was smart and well educated, especially for a woman at that time. A voracious reader, she spent much of that trip across the Atlantic plowing through books on slavery and discussing the subject with her fellow passengers. Being the wife of a delegate, she said, we all felt it important that I should be able to answer whatever questions I might be asked... on all phases of the slavery question.

Perhaps she studied slavery out of an obligation to her husband, but it was just as likely that she herself was deeply curious. After all, Stanton was, in some peoples eyes, less than ladylike. Passengers aboard the Montreal certainly took note that she called her husband Henry and not Mr. Stanton, as was customary back then. Elizabeth was assertive; she had demanded that she and Henry be married by a minister who would not force her to pledge to obey her husband, as tradition dictated. She kept her maiden name, Cady, announcing her determination that theirs would be a marriage of equals.

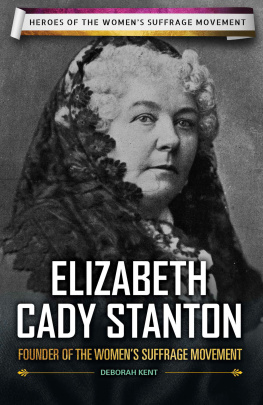

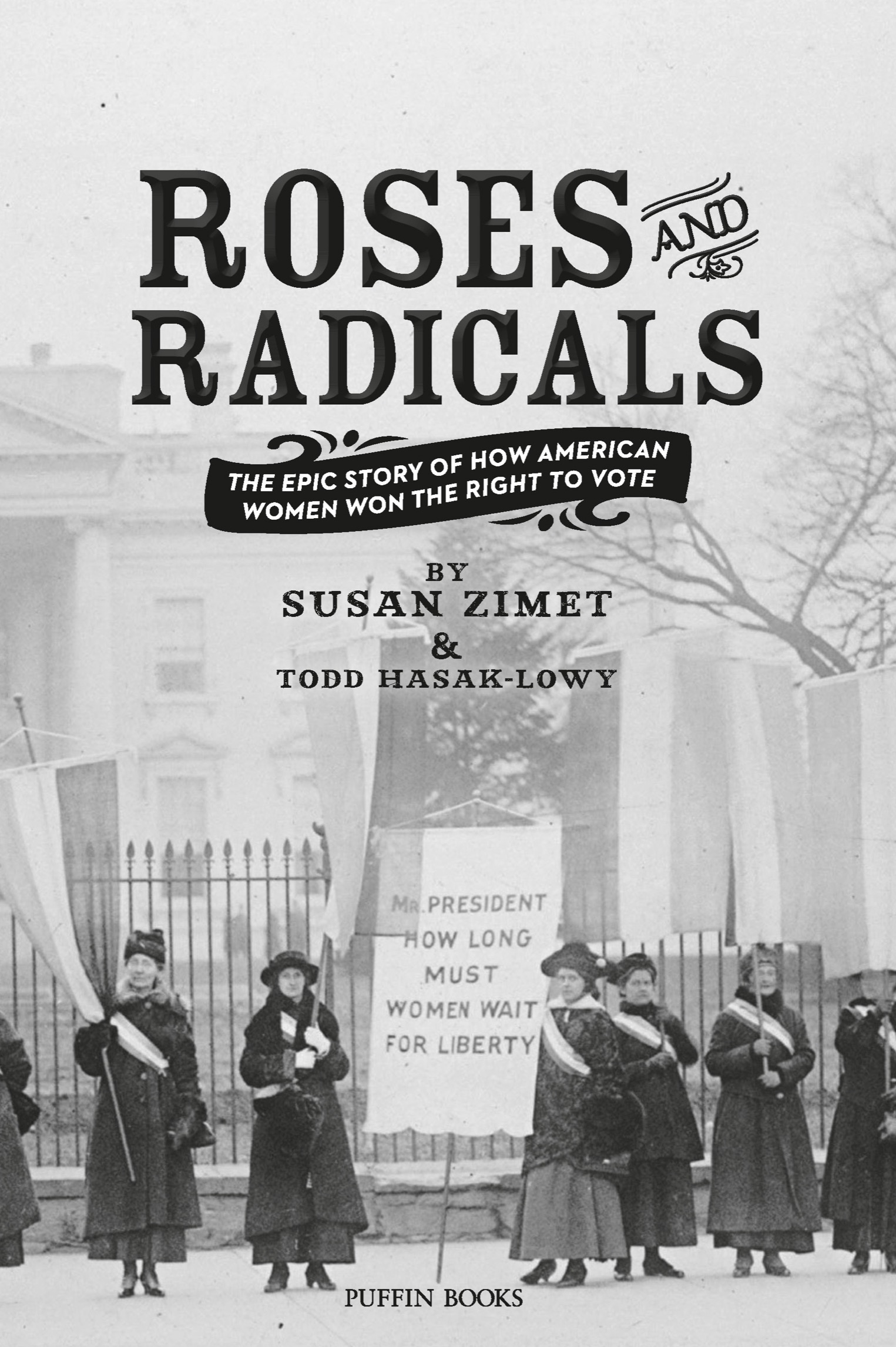

Elizabeth Cady Stanton with her daughter, Harriot, 1856. Harriot was the sixth of Stantons seven children.

Even though Elizabeth wasnt a delegate to the convention, other American women wereseven in all. In the second half of the 1830s women had steadily grown more visibleand more vocalin the American abolitionist movement. This didnt please everyone, and it led to major antislavery organizations splitting apart. Nevertheless, on June 12, 1840, male and female abolitionists together entered Londons Freemasons Hall to officially represent the American movement.

But only the men would be allowed to participate.

This was hardly the first time Elizabeth Cady Stanton witnessed the disadvantages of being female. Born in 1815 in Johnstown, New York, Stanton was one of eleven children, but she would be one of only five, all women, to make it to adulthood. Elizabeth was eleven when her last brother, Eleazar, died. She would forever remember finding her father, Daniel Cady, sitting in the dark parlor, pale and immovable, by the casket. Entering the room, she climbed up on his knee. He put his arms around her, but then sighed, Oh my daughter, I wish you were a boy!

However much this must have hurt to hear, Elizabeth pledged to somehow replace her brother, to be everything Eleazar no longer could be. Years later she wrote, All that day and far into the night I pondered the problem of boyhood. I thought that the chief thing to be done in order to equal boys was to be learned and courageous. Elizabeth was already brave, and she would get a fine education, at least in terms of what was available to girls at this time. Despite demonstrating over and over that her mind was equal to that of even the brightest young man her age, she would not receive a true college education.

Elizabeth steadily came to realize that her goal of equality would not be so simple. Time and again, she would encounter the endless restrictions placed against girls, to the point that she summed up her own girlhood with these words: Everything we like to do is a sin.... I am so tired of that everlasting no! no! no! At school, at home, everywhere it is no!

Her father was a lawyer and later a judge, and as a child Elizabeth often overheard his conversations with women who came to him for legal counsel. Even if a woman was in a terrible marriage in which the husband spent their money on drinking, gambling, and other women, even if the man beat her, she could not leave him without losing claim to their children. Fathers held all legal rights.

Daniel Cady tried to help these women, but there was little he could do. When Elizabeth got upset, he showed her the relevant passages in his law books. Not only this; he told her that when she grew up she should talk to the legislators; tell them all you have seen in this officethe sufferings of these Scotchwomen.... If you can persuade them to pass new laws, the old ones will be a dead letter.