CHAPTER 1

SMART, COURAGEOUS WOMEN

E arly in July 1848, an ad in an issue of a small upstate New York "newspaper stated:

A convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious rights of women will be held in the Wesleyan Chapel, Seneca Falls, New York, on Wednesday and Thursday, the 19th and 20th of July current; commencing at 10 a.m. During the first day the meeting will be held exclusively for women, who are earnestly invited to attend. The public generally are invited to be present on the second day.

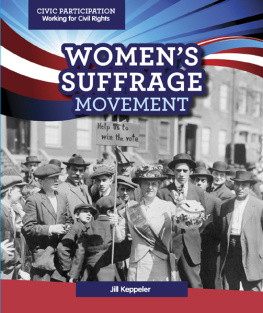

The meeting, attended by fewer than 300 people, marked the beginning of the womens rights movement in the United States. These early social reformers demanded civil rights for women. Chief among the rights was suffragethe right to vote. At the time no major nation in the world allowed female suffrage.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton speaks at the Seneca Falls convention.

There had been a few minor exceptions in the past. The Corsican Republic, which controlled the Mediterranean island of Corsica from 1755 to 1769, allowed womens suffrage. Also, at least one woman in the original 13 British American colonies actually voted. Her name was Lydia Taft. Because she was wealthy and influential in the town of Uxbridge, Massachusetts, she was allowed to vote in town meetings. In addition, between the years 1776 and 1807 the state of New Jersey allowed women who owned a certain amount of property to vote.

Such examples remained odd historical exceptions to a general rule in the vast majority of societies. It held that women were second-class citizens. They could neither vote nor run for public office. The main reason was that most people in those days simply accepted what they saw as gender norms. The common belief was that women were weak, incapable of complex thought, and ruled by their emotions.

In contrast, men were generally viewed as strong, complex thinkers, and in control of their emotions. It seemed logical, therefore, that men were better suited to hold down jobs and be in charge of politics. And as members of the perceived weaker, less capable gender, women were expected to run the home, raise the children, and support their husbands political views and personal dreams.

EDUCATED, PASSIONATE PEOPLE

The first major, organized attempt to change the situation in the United States was spearheaded by two smart, energetic, and courageous women. One was Lucretia Mott, who as a young woman had taught school in what is now Millbrook, New York. German-born social reformer Carl Schurz met Mott when she was 61. He later described her in these words: I thought her the most beautiful old lady I had ever seen. Her features were of exquisite fineness. Not one of the wrinkles with which age had marked her face, would one have wished away. Her dark eyes beamed with intelligence.

Lucretia Mott was a social reformer who also opposed slavery.

The other early founder of the U.S. womens movement was Elizabeth Cady Stanton. A devoted mother and social reformer, she lived in Seneca Falls, New York. The wearied, anxious look of the majority of women, she later wrote, impressed me with a strong feeling that some active measures should be taken to remedy the wrongs of society in general, and of women in particular.

Elizabeth Stanton and Lucretia Mott first met in 1840. At the time they were attending the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, England. There they found themselves surrounded by educated, passionate people like themselves. Stanton and Mott talked about putting together the same kind of gathering for womens rights.

Like many other women of their day, especially educated ones, Stanton and Mott felt that it was unfair that women had fewer rights than men. It was particularly upsetting that women could not vote or hold public office. Yet they did not desire these rights simply to gain political power. They saw the right to vote as a means to other ends as well. With more political power, women could more easily inherit property, for instance. They could also have a better chance of gaining custody of their children in a divorce. At the time men were awarded custody more often. The women also believed they could improve womens access to higher education. Most college graduates then were men.

For Stanton and Mott, the opportunity to organize a meeting to address these issues came eight years later. During the early summer of 1848, they and three other like-minded New York women agreed to hold a convention in July. To publicize it, they placed an ad in the Seneca County Courier.

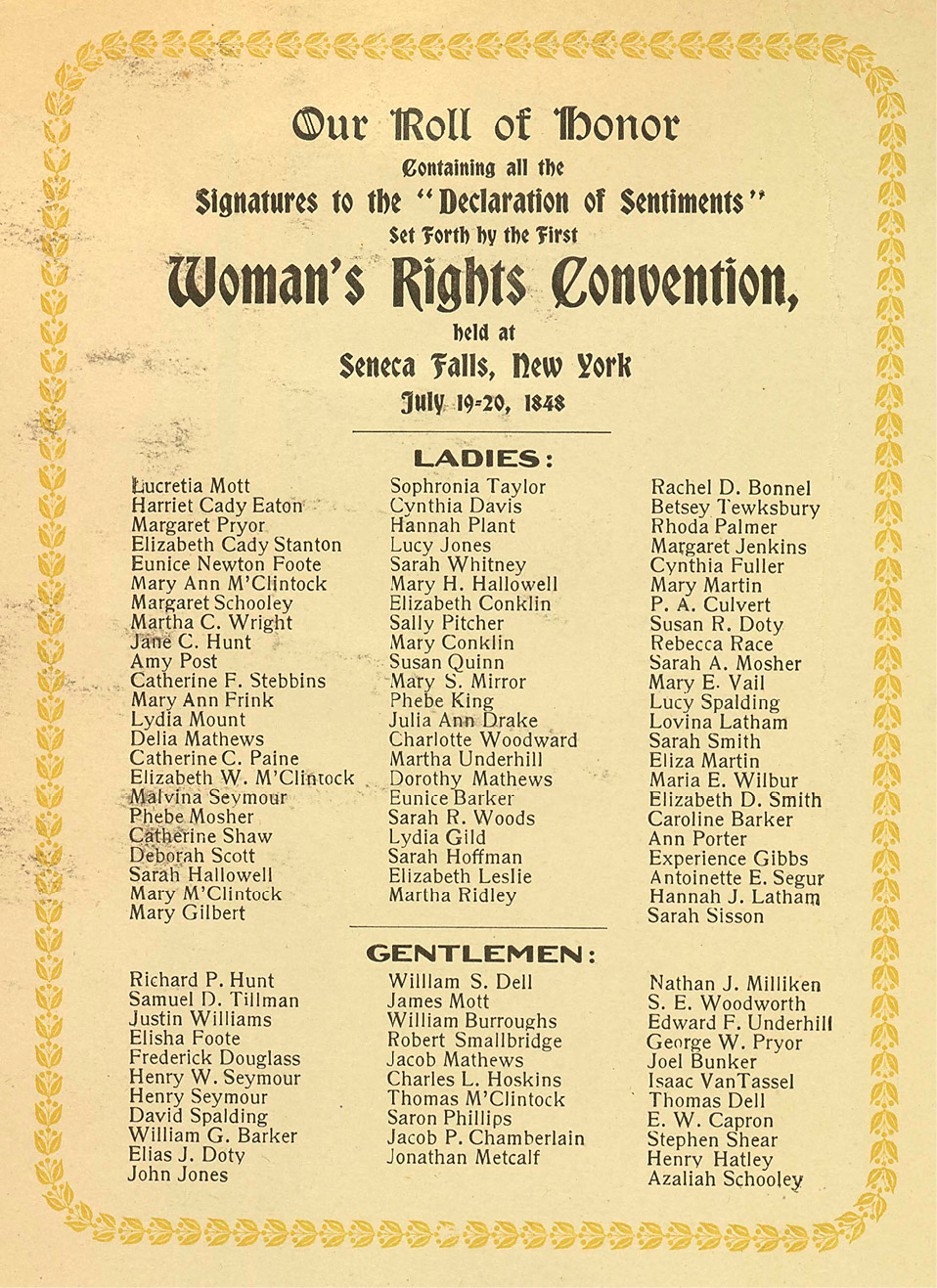

A roll of honor listed all those who signed the Declaration of Sentiments at the Seneca Falls convention in 1848.

ALL MEN AND WOMEN EQUAL?

The conference went even better than the organizers had hoped. About 250 women arrived on the first day. And even though the newspaper ad had called for attendance by women only that day, about 40 men unexpectedly showed up as well. One was the famous African-American social reformer Frederick Douglass. Mott, Stanton, and the other organizers happily welcomed the male attendees.

The event consisted mostly of speeches and discussions. Stanton gave one of the most moving speeches. The time had come, she declared, for the question of womens wrongs to be laid before the public. The issue of womans rights was of utmost importance, she stated. Furthermore, she and the others present dare assert that woman stands by the side of manhis equal.

Stanton also penned the meetings official written statement. Titled the Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions, it was purposely done in the format and style of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. One section of Stantons version stated: We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Among the most crucial rights women should have, the declaration said, was the right to vote. Existing governments, it continued, held what amounted to a tyranny over women. Because women could not vote, they had no say in choosing their leaders. And because they did not select those leaders, women had no real say in creating laws. Yet women were expected to obey the laws.

In the days following the convention, a number of newspapers and journalsall run by mencriticized the event. Women had no business voting, they said, and their demands for expanded rights were silly. But Mott, Stanton, and the meetings other organizers were convinced it had been a success. It will start women thinking, and men too, Stanton remarked. And when men and women think about a new question, the first step in progress is taken. History would later show she was right.

SCORN AND ABUSE

The right to vote was not the only womens issue that Elizabeth Cady Stanton fought for. She was also a tireless champion of female equality with men in employment, income, and custody of children in divorces. In a speech delivered in 1848, she pointed out: Every allusion to the degraded and inferior position occupied by woman all over the world, has ever been met by scorn and abuse. From the man of highest mental cultivation, to the most degraded wretch who staggers in the streets do we hear ridicule and coarse jests, freely bestowed upon those who dare assert that woman stands by the side of manhis equal.