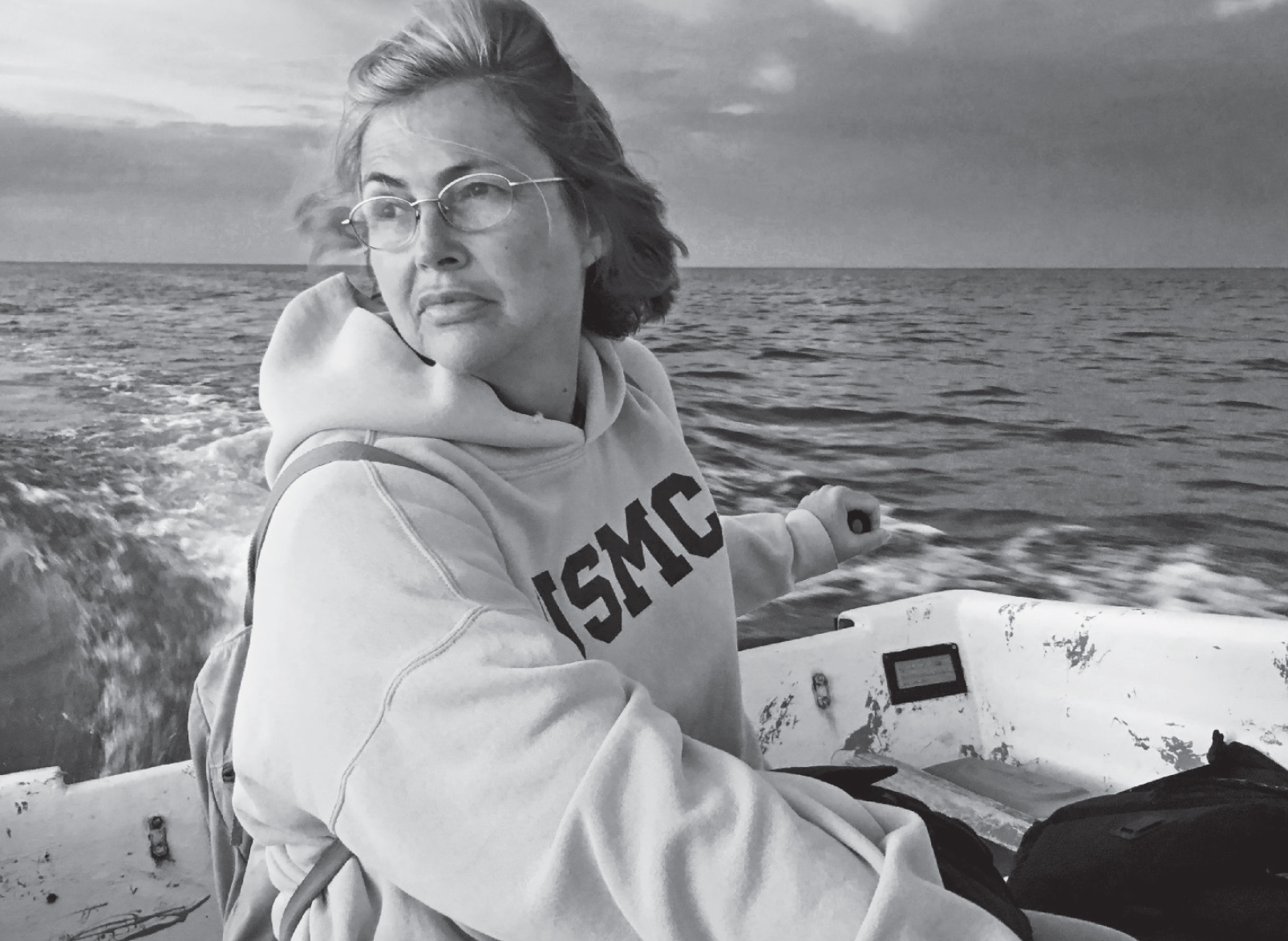

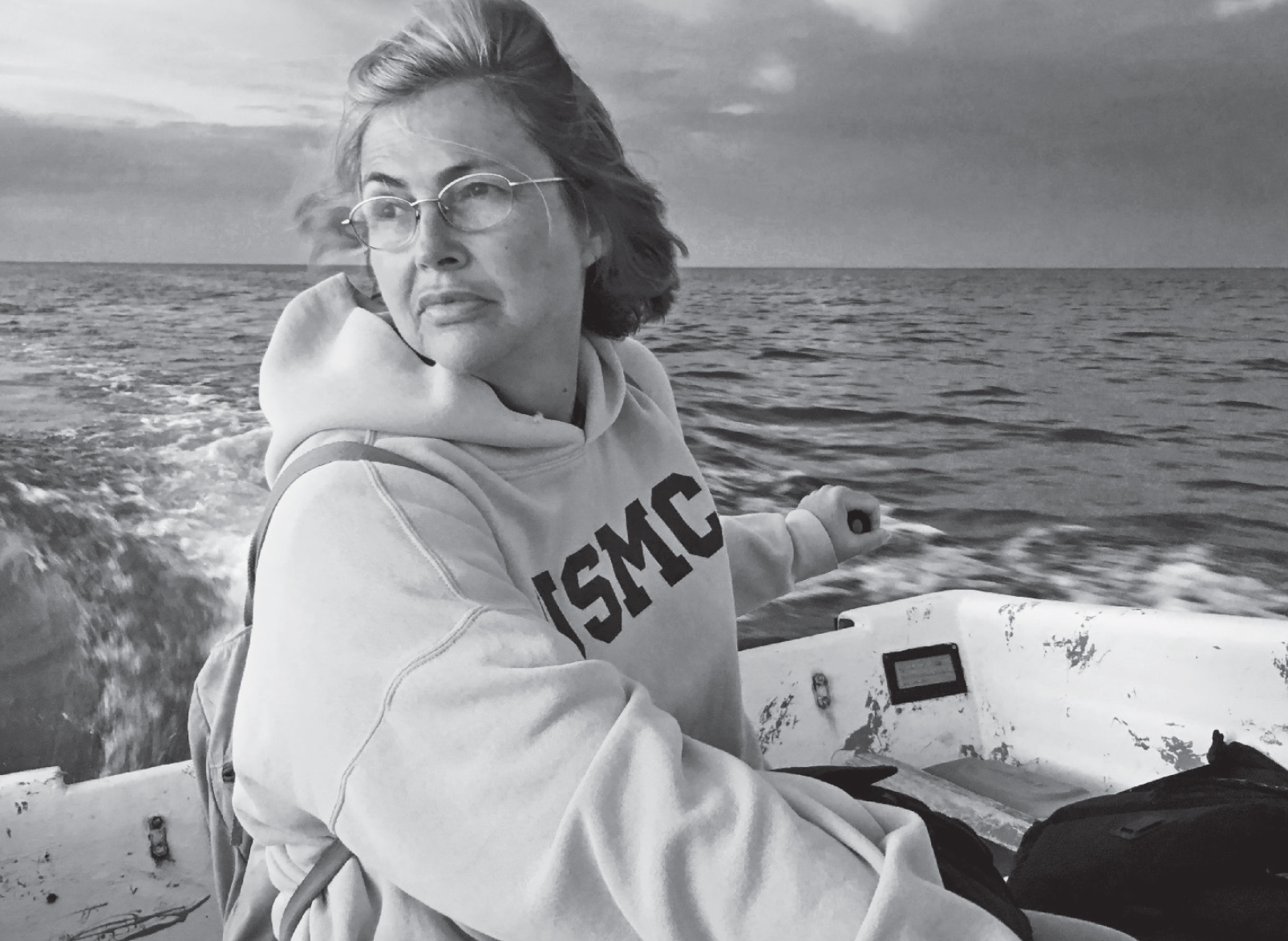

Carol Pruitt Moore undertakes her regular pilgrimage to Uppards. (E ARL S WIFT )

A DAY AFTER THE STORM PASSED , C AROL P RUITT M OORE climbed into her skiff and set off for the ruins of Canaan.

It was her habit to strike west from the harbor, into the channel that split her island in two. Shed throw open the throttle and crouch forward as the boats nose came up and its stern dug deep, her six-foot frame rocking against swells that thudded the fiberglass hull. One hand on the tiller, ball cap pulled low to cheat the wind, she would speed past the county dock and twenty-odd workboats parked off to port and, to starboard, a ragged line of crab shantiesweather-scoured sheds perched on stilts a few feet over the drink, surrounding decks stacked high with wire-mesh crab pots. A watery little business district, home to the greatest fishery of its kind in the world.

Out past the last of the shanties, the channel opened into the Chesapeake Bay, and most every day she threw the boat into a banking turn to the north. This time of year, she was running afoul of the prevailing winds, and if they were blowing against the tide, the journey would not be smooth. But like most of her neighbors, Carol Moore had been born into a seafaring family: She was the eighth generation of her kin born on Tangier Island, sixteen open-water miles from the nearest mainland town in Virginia. She could handle a boat before she could read.

On a typical afternoon shed hug the edge of a treeless, uninhabited marsh that islanders call Uppards, until a mile along she reached Tangiers northern tip, where a century past a community thrived. Canaan had long since washed away, but she found sanctuary on the deserted beach there, an escape from the close quarters and relative bustle of town. And more: She came upon tiny bottles once filled with patent medicines, offered by visiting drummers to island women a hundred years deadHamlins Wizard Oil, a nineteenth-century tonic for cancer, quinsy, and bites of dog, and Greenes Infallible Liniment, a cure-all For Man or Beast, and Turlingtons Balsam of Life, said in its day to cure kidney stones and inward weakness. She found eighteenth-century clay pipes and headless porcelain dolls. She collected bits of crockery, edges tumbled smooth by the surf.

Each relic she plucked from the sand was a tangible link to her forebears, for her fathers people had lived at Canaan for generations, back when it had its own school and a general store and thirty-odd houses, and had stayed until the last holdouts quit the place. By the time she was born, in 1962, that abandonment was decades passed, and none of Canaans buildings remained. But on childhood visits she had seen chickens and goats still roaming loose there, along with thickets of wild rose and rhubarb and so much anise that the whole place smelled like licorice. She remembered, too, walking deep into the marsh with her father, weaving among water bushes to a small cemetery far from the water. Its simple marble headstones testified to the lives of good Christians, loyal wives, hardworking watermen.

Here was where her great-grandparents had passed their days, and their parents, and theirspeople who persisted in her blood, her looks, her habits and manners. Here lay reminders of what she would become, and of the impermanence of all things. Some days she spent hours there, walking the waters edge. Others she stayed for just minutes. Almost always, she left for home feeling more sturdily, steadily grounded.

Only this afternoon promised to be different. For the previous three days, Tangier had been raked by Hurricane Sandy, its winds blowing a steady fifty knots or better, gusting past seventy. The gale had conspired with the tides to swamp the place. White-capped waves had rolled in from the east, breaking over streets and into homes. Water had surged through the channel, sweeping away anything not anchored firm. At high tide, only a few knobs of high ground and a single humpbacked bridge had escaped the flood.

Now, with the air scrubbed clean, whatever caught Moores eye revealed itself in preternatural detail. A few crab shanties had been flattened, and even from a distance their staggered plywood showed off its grain, and the wounds in their smashed planking gleamed a sunny, surreal yellow. Crab pots were strewn in the shallows. Pieces of roof and pier lay twisted among the reeds at the waters edge. Skiffs were sunk to their gunwales.

She sped into the bay. It was a sunny afternoon, cloudless, the sky a deep and flawless blue, the water flatslick calm, as the watermen say, which leaves Tangier lips as slick cam. Back in town trees were down, yards lay piled with trash that the tide had lifted from the marsh, and families were dragging ruined furniture and carpeting outside; to experience such peace out here, just hours after the storms mayhem, seemed unreal.

Sure enough, when she rounded the islands northern tip, she saw that the gale had not spared Canaan. The shoreline had been broken into pieces, cleaved by three new channels. Much of the sand that shed walked for years had been ripped away, and minus this protective buffer, the Chesapeake now lapped against the dark sod in which the islands marsh grass was rooted. The soil crumbled with each pulse.

She motored along the waters edge until she found a place to land the boat, and as she scrambled out she noticed something a foot or two offshore: a stained brown sphere half submerged in maybe six inches of water, rocking gently with the push and pull of the waves. As she stepped nearer she saw there were two of them. After a moments hesitation she bent down for one, and came up with a human skull.

It was well preserved, its hollows rinsed clean by the agitation of the surf. That of an adult, it appearedthough all of its upper teeth were missing and its lower jaw, too, so it was hard to reckon much beyond that. She rescued its mate, finding it in similar condition, and rested both on the ground well above the tide line.

She was struggling to digest her discovery when her eyes fell on a succession of familiar shapes at her feeta rib cage first, then clavicles, then a pelvis and all the other components of a human skeleton, down to the tiniest bones of the toes. The remains lay faceup in bas-relief, topmost inch exposed, the rest still encased in clay. Around them lay the traces of a coffin, and around that, a sharp-edged rectangle cut into the earth: a grave.

And lo, a few feet away was a second grave, and in it a second complete skeleton, likewise only partially exposed, with hair combs held fast by the clay on either side of its skull. And beyond that, a third grave, containing a tiny casket inside a bigger coffin, and nested in the middle the skeleton of a small child, perhaps no more than a toddler. Its shroud had long since succumbed to rot, but two bright white buttons that had held the garment closed were aligned on the childs breastbone.