Copyright 2003 by Earl Swift

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Swift, Earl, date.

Where they lay: a forensic expedition in the jungles of laos / Earl Swift,

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-618-16820-6 (hardcover)

ISBN 0-618-56242-8 (pbk.)

1. Vietnamese conflict, 19611975Missing in action United States. 2. Vietnamese conflict, 19611975 CampaignsLaos. 3. Barker, Jack. I. Title.

DS 559.8. M 5 S 95 2003

959-704'38dc21 2003041717

Maps and diagrams by Robert D. Voros

e ISBN 978-0-544-63995-9

v2.0718

1

T HEIR BUDDIES called it suicide, and maybe it was.

They climbed aboard the Huey knowing the enemy expected them. They did it knowing their guns were no match for the cannons that waited. They knew theyd be lucky beyond hope to get past them, and luckier still to get back. They climbed aboard the Huey just the same.

Time was short. Just over the border, their allies were surrounded and outnumbered and taking heavy fire. They depended on the four aboard the helicopter to get them out.

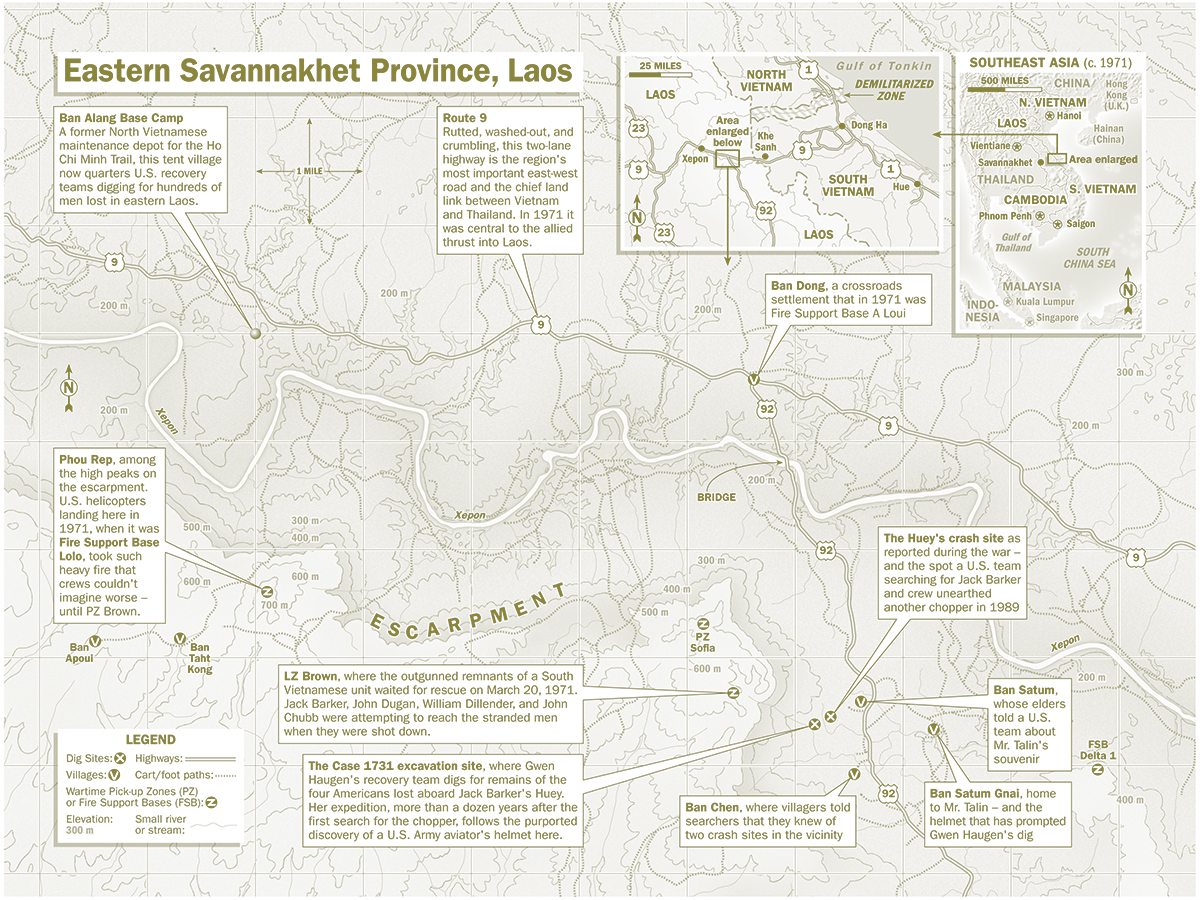

So on a Saturday in March 1971, the Huey skimmed over the mountains into the wide, wild valley beyond, following a rutted, two-lane highway into Laos. The country below was a tangle of splintered hardwoods and sheared bamboo, the jungles floor laid bare in wounds that stood fresh and red against the green. Off to starboard, a chain of low hills marked the northern edge of the Xepon Rivers flood plain. Looming ahead was its southern boundary, an escarpment a thousand feet high that showed its bones in cliffs streaked pink and gray. Worn into the rock was a notch a kilometer wide. In it was the pickup zone.

The flak started miles out. The Hueys pilots slalomed the bird among arcing yellow tracers and blooms of brown smoke as it dropped toward the target. Its gunners opened fire with their M-60s, sweeping the trees on the helicopters final approach.

The reply was overwhelming: Bullets raked the choppers thin metal skin, whistled into the cabin, tore into man and machine. Then came something worsea blur, rising from the trees, a telltale plumeand a flash. Fire swallowed the Huey. It hit the ground in pieces.

Other choppers circled low over the burning wreckage, crews marking the spot on their charts. None landed. North Vietnamese soldiers swarmed the bamboo thickets and forest around the smashed chopper, too many to risk a recovery mission. America was forced to leave the Huey, and the four, where they lay.

Which is what brings me, on a gray summer morning thirty years later, to a vibrating seat in the cabin of a Russian-built Mi-17 helicopter. And why its course takes me from a former American air base beside the Mekong River into the same valley, toward the same rampart of cliffs, in the battered highlands along the Vietnam-Laos border.

Somewhere down there is whats left of Jack Barker, John Dugan, Billy Dillender, and John Chubb. For two generations their remains have lain in a remote corner of this remote land, as bamboo and hardwood saplings erupted into new jungle around them, as monsoon rains scoured the red-clay earth and swooning heat baked it dry. Their comrades have grown old. Their children have had children of their own. Today, finally, their countrymen have arrived to take them home.

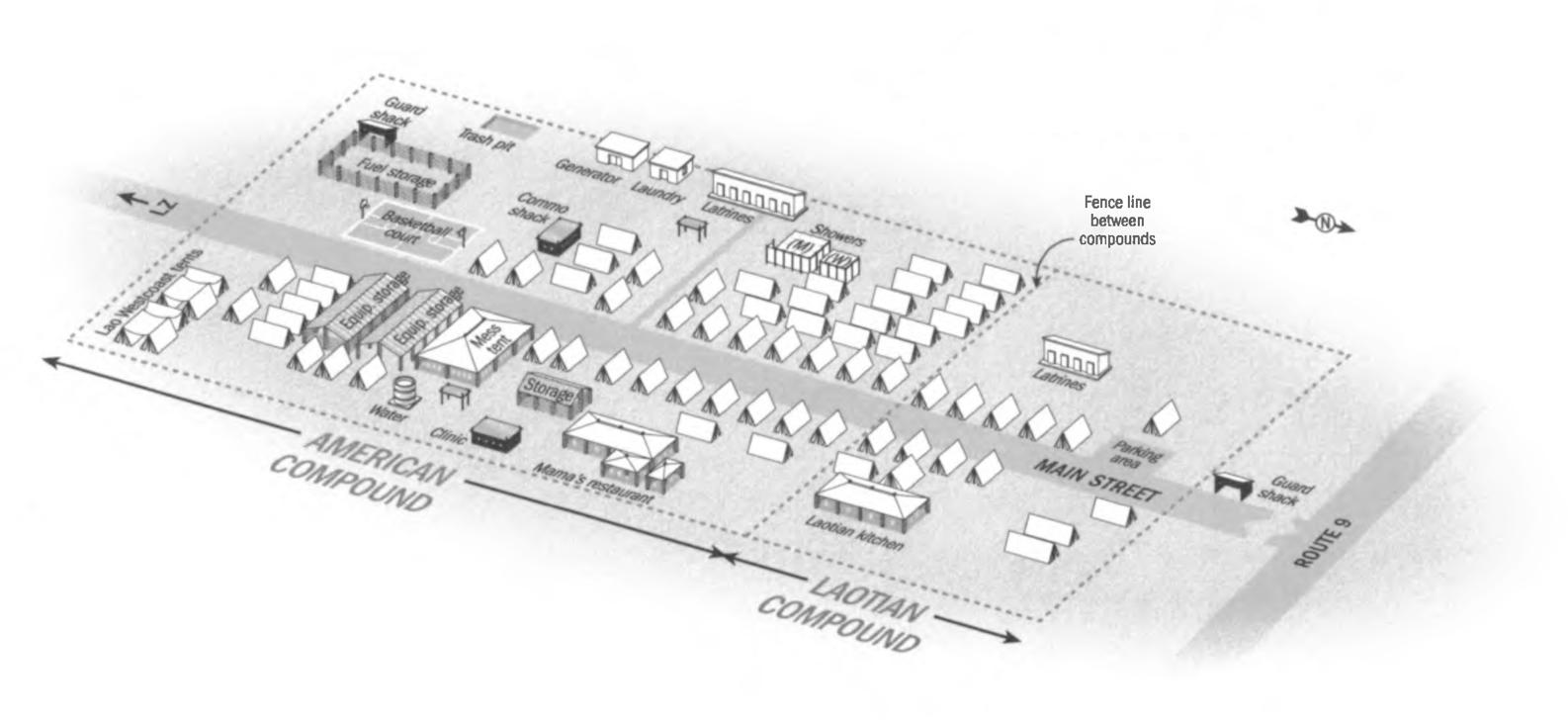

Sitting beside me are the soldiers and scientists, most too young to remember the war, who will search for the Hueys crew, men and women who for the next four weeks will live in a camp of canvas and nylon and lashed bamboo in the Laotian back country, and who will pass their days on an archaeological dig carved into the wilderness.

They will commute to work in craft all too similar to the ruined machine they seek, and face a host of dangers once they landsteep terrain, triple-digit temperatures, withering humidity, and thickets aswarm with scorpions, foot-long centipedes, and bright green vipers so venomous their nickname is Jake Two-Steps, said to be how far their victims get before dropping.

The mosquitoes carry malaria, and dengue fever, and God knows what else. Tigers patrol the jungle. And if this werent worry enough, the ground is laced with unexploded ordnance, leftovers of the fighting that claimed Jack Barker and his crewhalf-buried bombs and antitank mines and rockets and grenades and baseball-sized bomblets that, jostled the slightest bit, can all these years later turn an arm or leg into a puff of pink smoke.

The Mi-17 is short on frills. The cabin smells of exhaust. The sound of the rotor varies from deafening whine to bone-jolting bass chord. Hot wind buffets in through open portholes. The floor is plywood; the bare-metal bulkheads are stenciled with instructions in Cyrillic. It has the look and ambiance of an old and neglected school bus.

Only school buses dont yaw sickeningly as they travel. They dont boast clamshell doors like the big pair forming the cabins back end, doors between which I can see a thin but significant stripe of bright Asian airspace. I watch the gap for a while, see that its width keeps time with the Mi-17s shivers, which course through the frame like a dog shaking dry.

School buses arent typically driven by committee either. The helicopters cockpit is crowded with Laotian military men. I can see four of them from where I sit, all speaking and pointing past a pair of jerky windshield wipers into the sky ahead. All are in bits and pieces of uniform. The pilot is a skinny guy in a bright yellow T-shirt. His left hand is pressed against his headset, as if he cant hear over the chatter around him.

There are a couple dozen of us aboard, squeezed into troop seats that line the cabins sides. My view of those on the far side is blocked by luggage stacked four feet high down the length of the wide aisle. None of it is tied down. The pilebackpacks and suitcases, hard-cased gear and toolsteeters with each banking turn the big chopper makes. Somewhere behind us, another Mi-17 carries a similar load of people and equipment, and sprinkled elsewhere in the sky are four smaller Euro-copter Squirrels, carrying a handful of people apiece.

In all, fifty Americans are in the air. Most work for the U.S. Armys Central Identification Laboratory, where thirty civilian anthropologists and more than one hundred military specialists perform forensic detective work under the microscope and in the wildest of wilds, all aimed at bringing home those lost in Americas wars. Others are with Joint Task ForceFull Accounting, a puree of the different services that manage the labs visits to Southeast Asia and conduct the research that pinpoints where its teams should dig.

Beyond the rain-streaked porthole behind me, wispy clouds race past. I push my forehead against the glass to see the ground below, catch a glimpse of squares and trapezoids and narrow rectangles of bright green, a quiltwork of rice paddies stitched together with dikes that follow the lands irregular contours. A cloud interrupts the view. Then another. A moment later we fly through a bigger, thicker mat of vapor, and then theres nothing but white out there.