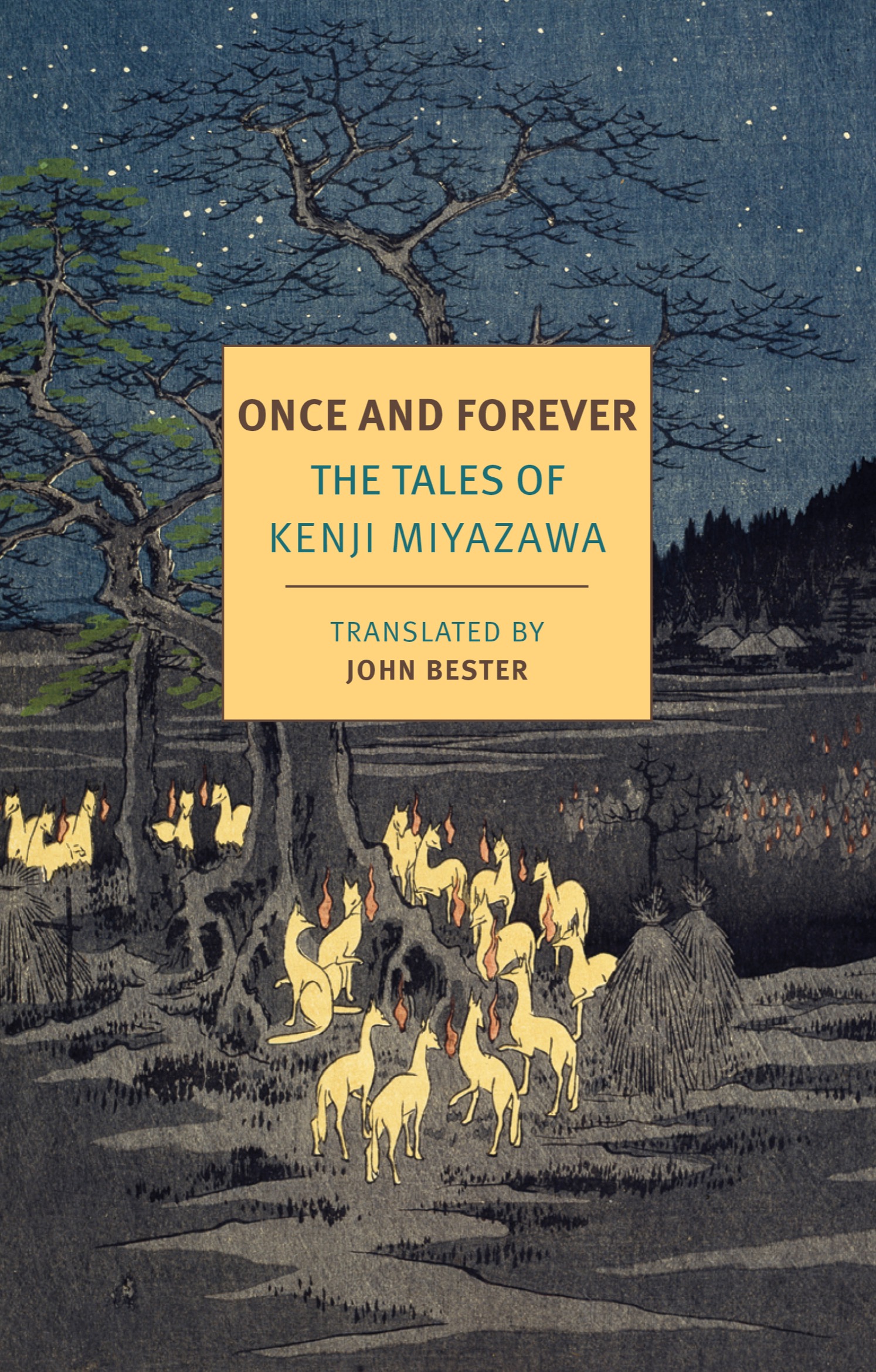

KENJI MIYAZAWA (18961933) was born in Iwate Prefecture in the northeast region of Japan into a prosperous mercantile family that had become devoutly Buddhist. As a teenager, he wrote classic tanka poems and discovered the Lotus Sutra, a text that would remain an influence throughout his life. Rejecting the family business, Miyazawa attended an agricultural college, studying modern farming techniques. After graduation, he moved to Tokyo where he wrote and worked as a proofreader, returning home to care for a sick sister in 1921. He remained in Iwate for the rest of his life, devoting himself to the cause of educating and improving the conditions of impoverished farmers. He died of tuberculosis at the age of thirty-seven, his health weakened by the strict diet he observed in solidarity with the local peasantry. Only two works of Miyazawas appeared during his lifetime, both in 1924: a self-published collection of poems titled Spring and Asura and a volume of fables translated as The Restaurant of Many Orders. The poems in particular were well received, establishing Miyazawa as a promising young writer, but it was not until after his death, with the publication of many of the manuscripts he had left behind, that he gained full recognition. During the 1940s, the Japanese government used his poem November 3rd as nationalist propaganda and it remains one of the best-known verses in Japan to this day. Miyazawas work was largely unknown to English speakers until the late 1960s and 70s, when it was championed by writers such as John Bester, Hiroaki Sato, and Gary Snyder. More recently, Miyazawas fables have become popular sources for anime adaptations and the inspiration for a childrens park in his home prefecture.

JOHN BESTER (19272010) attended the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London. Among the works he translated are Fumiko Enchis The Waiting Years, Masuji Ibuses Black Rain, Kenzaburo Oes The Silent Cry, and Yukio Mishimas Acts of Worship: Seven Stories, for which he received the Noma Award for the Translation of Japanese Literature.

ONCE AND FOREVER

The Tales of Kenji Miyazawa

Translated from the Japanese by

JOHN BESTER

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Translation copyright 1993 by John Bester

All rights reserved.

The Japanese titles of the stories collected in this volume are, in consecutive order: Tsuchigami to kitsune; Hokushu-shogun to sannin kyodai no isha; Otsuberu to zo; Shishi-odori no hajimari; Nametokoyama no kuma; Donguri to yamaneko; Sero-hiki no Goshu; Tokkobe Torako; Yomata no yuri; Chumon no oi ryoriten; Yamaotoko no shigatsu; Dokumomi no sukina shocho-san; Horakuma-gakko o sotsugyo shita sannin; Suisenzuki no yokka; Manazuru to dariya; Kairo-dancho; Tsue nezumi; Matsuri no ban; Kai no hi; Tsukiyo no den-shinbashira; Ken ju koen-rin; Yamanashi; Hayashi no soko; and Yodaka no hoshi.

Cover image: Utagawa Hiroshige, Foxes meeting at Oji, 1857; State Hermitage

Museum, St. Petersburg; photograph: akg-images

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Miyazawa, Kenji, 18961933, author. | Bester, John, 19272010, translator.

Title: Once and forever / Kenji Miyazawa ; translated by John Bester.

Description: New York : New York Review Books, 2018. | Series: NYRB classics | Stories first published in Japanese, translated into a new original, never before published collection.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018019071| ISBN 9781681372600 (paperback) | ISBN 9781681372617 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Miyazawa, Kenji, 18961933,Translations into English. | Short stories, JapaneseTranslations into English. | JapanFiction. | BISAC: FICTION / Short Stories (single author). | FICTION / Fairy Tales, Folk Tales, Legends & Mythology. | FICTION / Fantasy / Short Stories.

Classification: LCC PL833.I95 A2 2018 | DDC 895.63/44dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019071

ISBN 978-1-68137-261-7

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

T HIS collection is subtitled The Tales of Kenji Miyazawa. To refer to childrens tales would have been misleading from the outset; mere childrens tales could not have commanded, for some seventy years in a violently changing world, an increasingly wide following among adults. Here, surely, is one of those cases where the authorsome science-fiction and even crime writers are perhaps similarconsciously or unconsciously felt that he wanted to tell stories, and that he had something to say, but that neither the conventional novel with its well worked out theme and its more or less realistic approach, nor the self-consciously experimental novel, was to his taste.

Miyazawa, in fact, was first and foremost a poet: a poet concerned with particular beauties and general truths, a poet impatientone feelswith the provisory truths and temporizations of everyday, real society. He needed, if he was to tell stories at all, a different yet recognizable world in which to adumbrate his themes. For such a man, the type of tale seen here was ideal. The result could well have been merely whimsical, charming but slight. However, Miyazawas sensibility was too firmly rooted in a particular society, and in the realities of human existence, for him to fall into this trap.

The outcome of this approach is a body of storieswhether one calls them childrens tales or notthat can be enjoyed and in some measure understood, at least intuitively, at a fairly early age. But true appreciation of the poetry and of the overall message must await repeated readings and a certain degree of experience. So must appreciation of their literary qualities; the more one reads the more one sees how Miyazawa consciously experimented with themes and forms, fashioning and refashioning the tales as though they were poemswhich indeed, in a sense, they are.

Some of them approximate to the cautionary tale familiar in the West: works such as The Restaurant of Many Orders or The Fire Stone. At the other extreme stands The Wild Peartwo brief, plotless sketches that manage to encapsulate some of the cruelty of life on the one hand and its compensating beauties on the other. The tales that stand between these two extremes have a truly astonishing range. There is a group of what might almost be dubbed prose poems: The First Deer Dance, a fanciful account of the origins of a folk dance, still performed today, which builds up to an ecstatic paean to nature; The Red Blanket, a stormy snowscape, a symphony of white against which the red blanket of the title stands out as a poignantly human touch; and A Stem of Lilies, a kind of hymn to innocence. There is drama, too: in The Earthgod and the Fox, what promises to be no more than a whimsical tale about non-human characters develops into a moving little tragedy of considerable insight and compassion. And there are stories touched with a humor ranging from wry satire to outright farce.

In fact, no two of the tales are quite alike in their structure and flavor. The skill with which structure is matched to theme is conscious. Sometimes only rereading reveals the artful purpose that can lie behind apparent inconsequentiality, making one willing to give the benefit of the doubt even to what seems at first sight a comparative failure. The Thirty Frogs, for example, might seem to be spoiled by the