THE POETIC EDDA

THE POETIC EDDA

Translated with an Introduction

and Explanatory Notes

BY LEE M. HOLLANDER

SECOND EDITION, REVISED Stolen and delivered by

[DerHammer] For more material

visit us at:

Twitter: Twitter.com/HammerDer

Kickass.to: Kickass.to/user/DerHammer ISBN 978-0-292-76499-6

To the Memory of My MotherTable of Contents

General Introduction What the

Vedas are for India, and the Homeric poems for the Greek world, that the

Edda signifies for the Teutonic race: it is a repository, in poetic form, of their mythology and much of their heroic lore, bodying forth both the ethical views and the cultural life of the North during late heathen and early Christian times. Due to their geographical position, it was the fate of the Scandinavian tribes to succumb later than their southern and western neighbors to the revolutionary influence of the new world religion, Christianity. Before its establishment, they were able to bring to a highly characteristic fruition a civilization stimulated occasionally, during the centuries preceding, but not overborne by impulses from the more Romanized countries of Europe. Owing to the prevailing use of wood for structural purposes and ornamentation, little that is notable was accomplished and still less has come down to us from that period, though a definite style had been evolved in wood-carving, shipbuilding and bronze work, and admirable examples of these have indeed been unearthed. But the surging life of the Viking Agerestless, intrepid, masculine as few have been in the worlds historyfound magnificent expression in a literature which may take its place honorably beside other national literatures.

For the preservation of these treasures in written form we are, to be sure, indebted to Christianity; it was the missionary who brought with him to Scandinavia the art of writing on parchment with connected letters. The Runic alphabet was unsuited for that task. But just as fire and sword wrought more conversions in the Merovingian kingdom, in Germany, and in England, than did peaceful, missionary activity so too in the North; and little would have been heard of sagas, Eddic lays, and skaldic poetry had it not been for the fortunate existence of the political refuge of remote Iceland. Founded toward the end of the heathen period (ca. 870) by Norwegian nobles and yeomen who fled their native land when King Harald Fairhair sought to impose on them his sovereignty and to levy tribute, this colony long preserved and fostered the cultural traditions which connected it with the Scandinavian soil. Indeed, for several centuries it remained an oligarchy of families intensely proud of their ancestry and jealous of their cultural heritage. Even when Christianity was finally introduced and adopted as the state religion by legislative decision (1000 A.D.), there was no sudden break, as was more generally the case elsewhere.

This was partly because of the absence of religious fanaticism, partly because of the isolation of the country, which rendered impracticable for a long time any stricter enforcement of Church discipline in matters of faith and of living. The art of writing, which came in with the new religion, was enthusiastically cultivated for the committing to parchment of the lays, the laws, and the lore of olden times, especially of the heroic and romantic past immediately preceding and following the settlement of the island. Even after Christianity got to be firmly established, by and by, wealthy freeholders and clerics of leisure devoted themselves to accumulating and combining into sagas, the traditions of heathen times which had been current orally, and to collecting the lays about the gods and heroes which were still rememberedindeed, they would compose new ones in imitation of them. Thus, gradually came into being huge codices which were reckoned among the most cherished possessions of Icelandic families. By about 1200 the Danish historian, Saxo Grammaticus, already speaks in praise of the unflagging zeal of the Icelanders in this matter. The greatest name in this early Icelandic Renaissance (as it has been called) is that of Snorri Sturluson (1178-1241), the powerful chieftain and great scholar, to whom we owe the Heimskringla, or The History of the Norwegian Kings, and the Snorra Eddaabout which more laterbut he stands by no means alone.

And thanks also to the fact that the language had undergone hardly a change during the Middle Ages, this antiquarian activity was continued uninterruptedly down into the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when it was met and reinforced by the Nordic Renaissance with its romantic interest in the past. In the meantime the erstwhile independent island had passed into the sovereignty of Norway and, with that country, into that of Denmark, then at the zenith of its power. In the search for the origins of Danish greatness it was soon understood that a knowledge of the earlier history of Scandinavia depended altogether on the information contained in the Icelandic manuscripts. In the preface to Saxos Historia Danica, edited by the Danish humanist Christiern Pedersen in the beginning of the sixteenth century, antiquarians found stated in so many words that to a large extent his work is based on Icelandic sources, at least for the earliest times. To make these sources more accessible, toward the end of the sixteenth century, the learned which, with the kings of Norway in the foreground, tells of Scandinavian history from the earliest times down to the end of the twelfth century. Since it was well known that many valuable manuscripts still existed in Iceland, collectors hastened to gather them although the Icelandic freeholders brooded over them like the dragon on his gold, as one contemporary remarked.

As extreme good fortune would have it, the Danish kings then ruling, especially Fredric III, were liberal and intelligent monarchs who did much to further literature and science. The latter king expressly enjoined his bishop in Iceland, Brynjlfur Sveinsson, a noted antiquarian, to gather for the Royal Library, then founded, all manuscripts he could lay hold of. As a result, this collection now houses the greatest manuscript treasures of Northern antiquity. And the foundations of other great manuscript collections, such as those of the Royal Library of Sweden and the libraries of the Universities of Copenhagen and Uppsala, were laid at about the same time. This collecting zeal of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries may almost be called providential. It preserved from destruction the treasures, which the Age of Enlightenment and Utilitarianism following was to look upon as relics of barbarian antecedents best forgotten, until Romanticism again invested the dim past of Germanic antiquity with glamor.

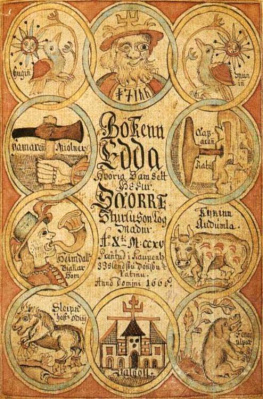

At the height of this generous interest in the past a learned Icelander, Arngrmur Jnsson, sent the manuscript of what is now known as Snorra Edda or The Prose Edda (now called Codex Wormianus), to his Danish friend Ole Worm. Knowledge of this famous work of Snorris had, it seemed, virtually disappeared in Iceland. Its author was at first supposed to be that fabled father of Icelandic historiography, Smundr Sigfsson (10561133), of whose learning the most exaggerated notions were then current. A closer study of sources gradually undermined this view in favor of Snorri; and his authorship became a certainty with the finding of the Codex Upsaliensis of the Snorra Edda, which is prefaced by the remark that it was compiled by Snorri. To all intents and purposes this

Next page