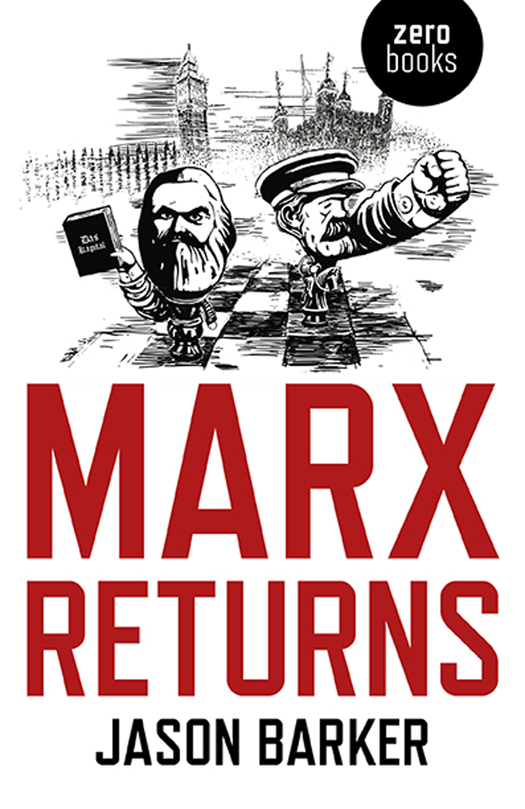

What people are saying about

Marx Returns

Set in a putrid prerevolutionary London marinating in the miasma of oppression and exploitation, Marx Returns is an uncanny alt-fiction that blows the past out of the continuum of history to revivify Marx the man, his life and his thought for our own age. Mixing tragedy with farce, mathematics with alcohol, Marx Returns gives us a great new take on a grand old tale.

Justin Clemens, author of The Mundiad

Curious, funny, perplexing, and irreverent an inspired divagation that casts unexpected light on Marxs thought.

Ray Brassier, author of Nihil Unbound: Enlightenment and Extinction

For years weve been led to believe that Marx was right. On the evidence of Jason Barkers debut novel, however, it seems we may have grossly underestimated him. Joyful, artful and playfully anachronistic, Marx Returns is a book youre unlikely to want to end.

Yong Soon Seo, Professor of Philosophy, Sungkyunkwan University

A Note on the Text

This is a work of historical fiction. Although it portrays true incidents in Karl Marxs life and includes original correspondence, the story often departs from the facts. Furthermore, in especially, the timeline has been greatly abbreviated.

Some of the made-up incidents are more plausible than others. For example, the meeting between Marx and Mikhail Bakunin in could not have taken place, since in November 1849 the latter was in prison in Knigstein. However, this is not to say that the two men would not have met had Bakunin managed to escape to London: they almost certainly would have done. As for the implausible incidents, readers are free to judge them in the context of the story. It was never my intention to write a Marx biography and I make no apologies for not having written one.

The novel draws on Marxs unpublished and published writings of the period. All translations from the Marx Engels Werke are my own unless otherwise stated. I am grateful to G. M. Goshgarian for his German translations.

Minor references to Marx and Engelss works are to English editions. Mindful of the fact that too many notes can be distracting, especially in a work of fiction, I have tried to keep them to a bare minimum. Mostly they contain contextual and historical information, references to real persons and primary and secondary literature. For quotations from Shakespeares plays I have chosen not to cite publishers or editions. There are several unacknowledged quotations from other works, notably Dantes Divine Comedy (all such works are in the public domain). There are also anachronisms, particularly in relation to chess.

Marxs interest in differential calculus dates from the final years of his life, whereas in the novel I have him grappling with mathematical formulas from the beginning. I am grateful to Anindya Bhattacharyya for his help and corrections of my use of mathematics. I am also grateful to Igor Kori for his many comments and suggestions on the manuscript, and for the engaging conversations on Marx, Marxism and revolution.

Jason Barker, Seoul, 12 June 2017

Chapter 1

News from Paris

Neue Rheinische Zeitung, No. 27

June 27, 1848

Cologne, 26 June. The latest news from Paris takes up so much space that we have no choice but to omit all analytical articles.

We accordingly offer our readers only a few briefs. Ledru-Rollin, Lamartine and their Ministers Resign; Cavaignacs Military Dictatorship Transplanted from Algiers to Paris; Marrast, A Dictator in Civilian Clothing; Paris Awash in Blood; Uprising Developing into the Greatest Revolution of All Time, the Proletariats Revolution against the Bourgeoisie. There is the latest news we have received from Paris. The three days that sufficed for both the July Revolution and the February Revolution will not be enough for this gigantic June Revolution, but the victory of the people is ever more certain. The French bourgeoisie has dared to do what the French Kings never did: it has itself cast the die. With this, the French Revolutions second act, the European tragedy is just beginning.

Chapter 2

London, 4 November 1849

On the Upper Lambeth Marsh the air was threatening to induce dizziness in any wayward soul. Not that any soul would ever be so possessed as to visit what Dietz had described as Hells waiting room. From sulphurous clouds the smouldering armour of the Whig parliament emerged in homage to the Great Fossil Lizard that once roamed the Thames Basin. On the South Bank, chimney stacks blasted out their molten debris in a barrage of volcanic eruptions. In Lambeth, the munitions factories sent projectiles skywards with such ferocity that the clouds seemed to ignite before returning the glowing debris back to earth.

In a democratic understanding of sorts, perhaps the signal achievement of the times, the fiery rain fell on top hats and flat caps in equal measure. For anyone crossing the damp element by Westminster Bridge, the threat of tumbling masonry compounded that of falling debris; which, on occasion, would seal the thanks-offering fate of drunks, college-goers and lunatics. On the narrow stretch offshore, in easy range of the cannonade, steamboats and Thames barges jostled for control of the quays and wharfs. Lighters ferried cargo from the bulkier craft and, as if to complete the aquatic food chain, workers in rowboats hawked beer to the lightermen.

Whether or not the seismic activity of bourgeois industry would one day come to rival the Triassic extinction event in its environmental impact was unclear. For the moment, however, what struck the spectatorthe one inclined to doubt the evidence of their own eyeswas not remotely how things had evolved thus, or where they might in future, but whether or not any of it could really be described, at all. What exactly was one looking at?

Sir! Pay me a penny for my cat, say.

Marx glanced up from his notebook. A gang of street urchins approached, rehearsed in their own variety of extinction event. The ringleader, genderless and caked in mud, dangled an animal from a cord, more rodent than feline, though not long for this world. He thrust the petrified creature at Marx in plain ignorance of the fact that both animal and tormentor shared a common ancestor.

I-I-I Marx faltered and the creature responded in kind.

You-you-you, replied the tormentor and the apprentice demons cackled.

Raus mit euch, Ihr Tierquler! Marx would have declared next, had his English been up to the mark.

The creature was almost human. Its bloodshot eyes and pulsating nostrils might have been those of Marxs landlord on rent day. Indeed, but for the unfortunate mystery of the animals capture, the break in the organic chain might have been minutely deferred. Of such unpredictable encounters was history woven. (The class struggle could surely be traced back to the dark wood of savageryif not beforewhen man was a mere tree-dweller among beasts.)