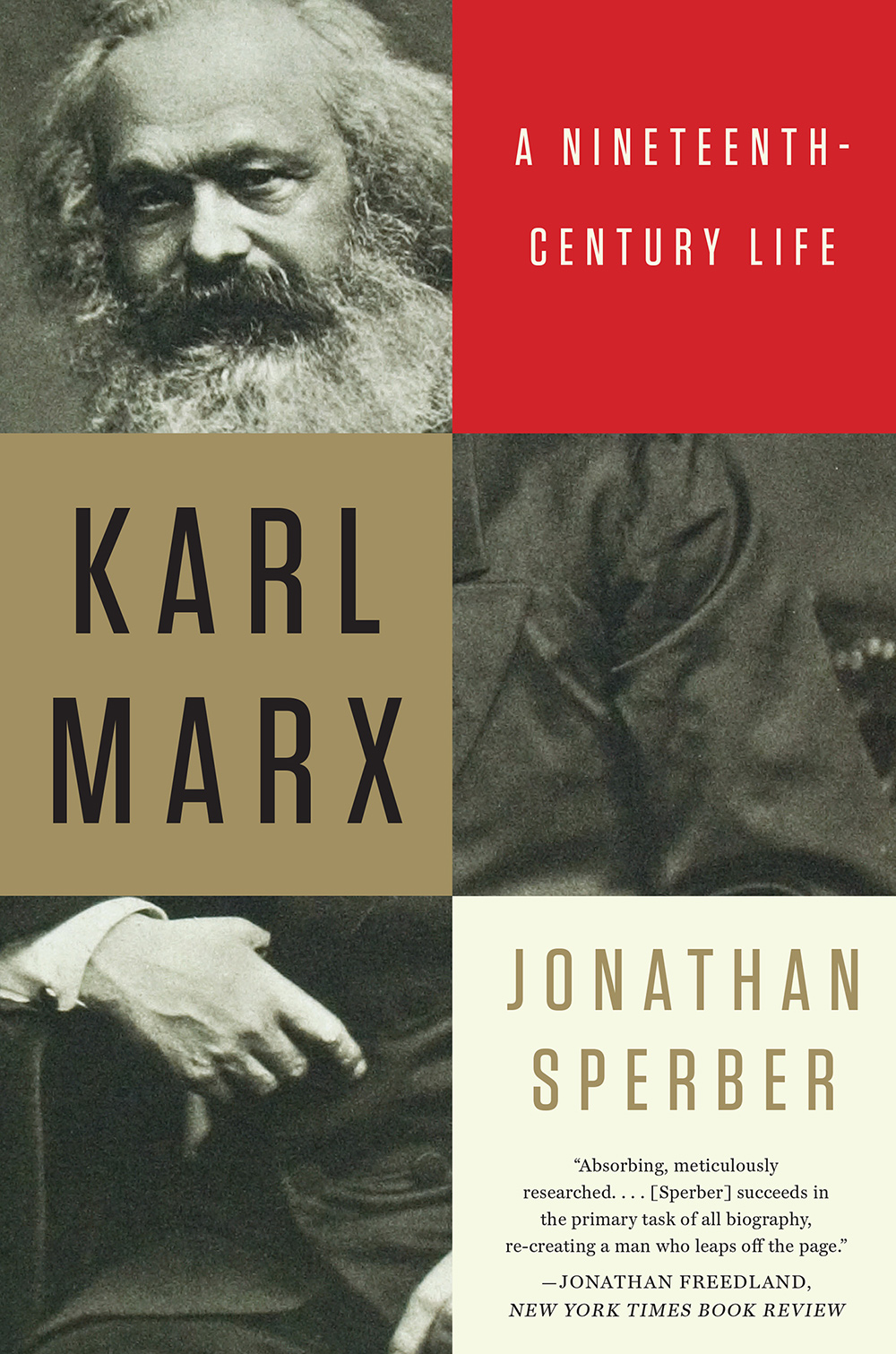

Karl Marx

A NINETEENTH-CENTURY LIFE

JONATHAN SPERBER

This book is dedicated to the memory of

my father

LOUIS SPERBER

Contents

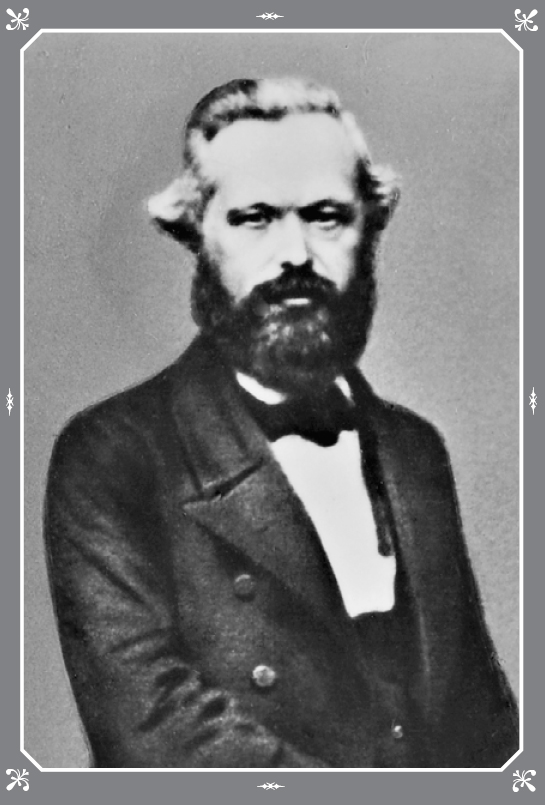

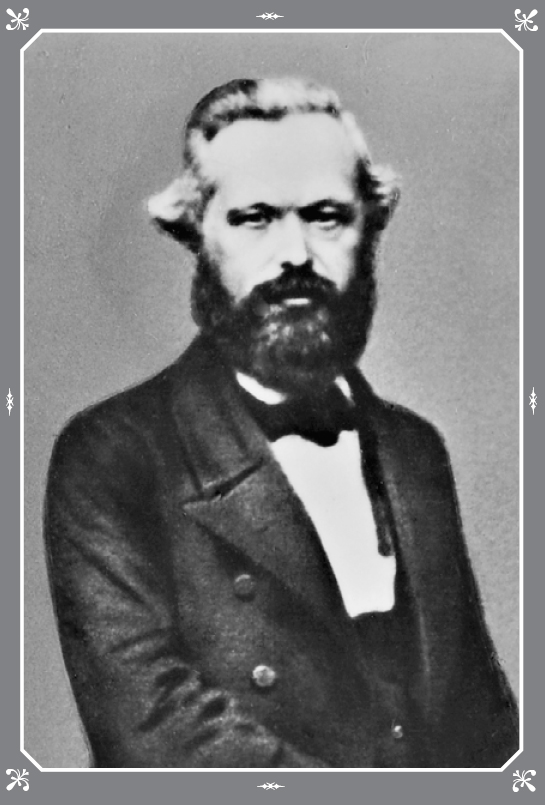

EARLY IN THE WINTER of 1848 in the Belgian capital of Brussels, a man, short but broad-shouldered, still youthful-looking, his dark hair and beard nonetheless showing the first streaks of gray, sat at a desk in a poorly furnished apartment. He was writing, as he usually did, in fits and starts. For a while his pen moved across the paper, in a barely legible left-handed scrawl, then he would break off, stand up and pace around his desk, before returning, crossing out parts of what he had written, and starting again. His family membersa wife a few years older than he was, two small daughters, and an infant son, along with a single servant, her presence testifying to the gap between her employers social expectations and their financial circumstancesleft him alone in his labors. They knew that the piece was overdue for delivery to the publishers, a chronic problem for his literary work.

The man and father was Karl Marx, and his writing, past its deadline to be sent to the Central Authority of the Communist League in London, was the Leagues new political statement, its Communist Manifesto . For so many historians and biographers, this Manifesto and the life of intellectual inquiry and political struggle to which it was connected was that of a modern contemporary, a nineteenth-century figure who had looked deeply into the future and helped to shape that future, whether for good or for ill. This understanding of Marx as a controversial contemporary appears in one of the very first biographies of him, published in 1936 but still well worth reading. It is rarely cited, for its title is embarrassing to current sensibilities: Boris Nicolaievsky and Otto Maenchen-Helfens Karl Marx: Man and Fighter :

Strife has raged about Karl Marx for decades, and never has it been so embittered as at the present day. He has impressed his image on the time as no other man has done. To some he is a fiend, the arch-enemy of human civilization, and the prince of chaos, while to others he is a far-seeing and beloved leader, guiding the human race towards a brighter future. In Russia his teachings are the official doctrines of the state, while Fascist countries wish them exterminated. In the areas under the sway of the Chinese Soviets Marxs portraits appears upon the bank-notes, while in Germany they have burned his books.1

Viewed positively, Marx is a far-seeing prophet of social and economic developments and an advocate of the emancipatory transformation of state and society. From a negative viewpoint, Marx is one of those most responsible for the pernicious and evil features of the modern world.

As the passage from Nicolaievsky and Maenchen-Helfens book suggests, these strongly polarized opinions about Marx were a reflection of the major twentieth-century conflicts between communist regimes and their opponents, both totalitarian and democratic. Yet even after the end of most communist regimes in 1989, this view of Marx as our contemporary has remained. In 1998, at the time of the 150th anniversary of the Communist Manifesto , there were frequent references to Marx as someone who had predicted the consumerist future; the eminent historian Eric Hobsbawm suggested that Marx and Engels 1848 treatise had foreseen the age of globalized capitalism. One might expect Hobsbawm, himself a Marxist, to assert the continued validity of the ideas he espoused over the course of his long lifetime. Yet in the global economic crisis of the fall of 2008, the headline in The Times of London, a newspaper above any suspicions of communist sympathies, screamed: Hes back! Frances right-wing president, Nicolas Sarkozy, was photographed thumbing through Capital . Apparently Marxs status as a contemporary is very long lasting.2

Here it seems appropriate to ask how a mortal human being, and not a wizardKarl Marx, and not Gandalf the Greycould successfully look 150 or 160 years into the future. A closer examination of the Communist Manifesto itself, with its vision of a recurrence of the French Revolution of 1789, its reiteration of the theories of early nineteenth-century political economists, its veiled references both to the philosophy of G. W. F. Hegel and to the new anti-Hegelian ideas of positivist scholarship, its many insider references to Marxs own past and to what are today obscure features of the European politics of the 1840s, suggests something quite different. The view of Marx as a contemporary whose ideas are shaping the modern world has run its course and it is time for a new understanding of him as a figure of a past historical epoch, one increasingly distant from our own: the age of the French Revolution, of Hegels philosophy, of the early years of English industrialization and the political economy stemming from it. It might even be that Marx is more usefully understood as a backward-looking figure, who took the circumstances of the first half of the nineteenth century and projected them into the future, than as a surefooted and foresighted interpreter of historical trends. Such are the premises underlying this biography.

Complementing these new premises is a remarkable fresh source for Marxs life and thought, the complete edition of the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, generally known by its German acronym as the MEGA . This enormous project began in the Soviet Union during the 1920s. Its very energetic first editor, David Rjazanov, was arrested in one of Stalins great purges and later shot, bringing the first phase of the project to an end. Work resumed in 1975, sponsored by the Institutes of Marxism-Leninism in East Berlin and Moscow. After 1989 and the end of communism in Eastern Europe, the project has continued, housed in the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, and directed by the International Marx-Engels Foundation. The editions finances come from the government of a united Germany, initially thanks to the projects endorsement by the conservative architect of German unification Chancellor Helmut Kohl, himself by training a historian. This very large scale scholarly undertaking, still ongoing today, aims to publish everything Marx and Engels ever wrote, including the notes they scribbled on the backs of envelopes. Unlike less complete editions of the two mens works, it does not just print the letters Marx and Engels themselves composed, but the letters addressed to them as well. This new source contains no smoking gun, no single document that completely alters existing understandings of Marx; but it does bring to light hundreds of small details that subtly change our picture of him.3

The MEGA was originally part of a broader Cold War publishing competition that pitted the communist heirs of Marxs ideas in East Berlin and Moscow against his social democratic ones at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Bad Godesberg, and the Karl Marx House in Trier. Unlike most Cold War competitions, this one had useful results, including a flood of source publications, narrowly focused monographs, and highly detailed scholarly articles providing a mass of information about Marxs life and timesoften printed in obscure venues and little used or not at all in previous biographies.

Next page