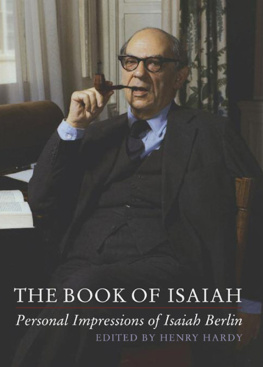

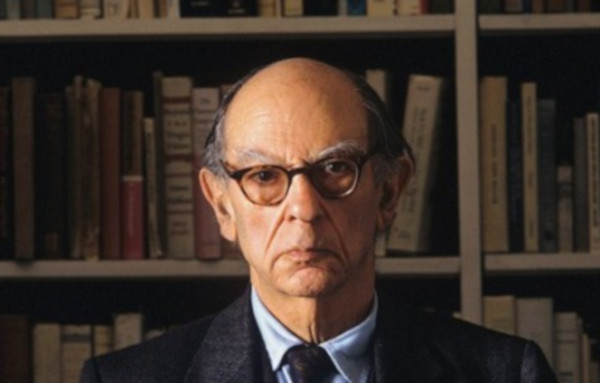

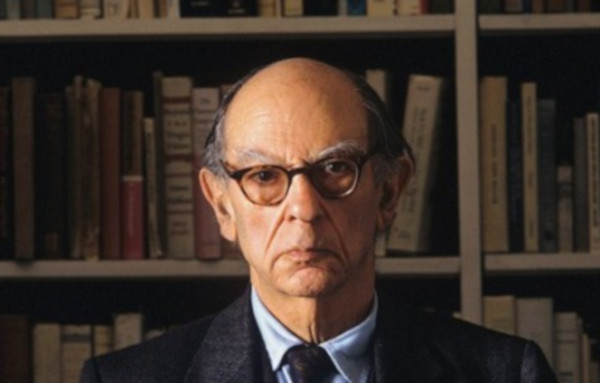

ISAIAH BERLIN WAS BORN IN RIGA, now capital of Latvia, in 1909. When he was six, his family moved to Russia; there in 1917, in Petrograd, he witnessed both revolutions social democratic and Bolshevik. In 1921 he and his parents came to England, and he was educated at St Pauls School, London, and Corpus Christi College, Oxford.

At Oxford he was a Fellow of All Souls, a Fellow of New College, Professor of Social and Political Theory, and founding President of Wolfson College. He also held the Presidency of the British Academy. In addition to Karl Marx, his main published works are Russian Thinkers, Concepts and Categories, Against the Current, Personal Impressions, The Crooked Timber of Humanity, The Sense of Reality, The Proper Study of Mankind, The Roots of Romanticism, The Power of Ideas, Three Critics of the Enlightenment, Freedom and Its Betrayal, Liberty, The Soviet Mind and Political Ideas in the Romantic Age. As an exponent of the history of ideas he was awarded the Erasmus, Lippincott and Agnelli Prizes; he also received the Jerusalem Prize for his lifelong defence of civil liberties. He died in 1997.

To the memory of Marie and Mendel Berlin

Original title: Karl Marx

Isaiah Berlin, 1939

Diseo de cubierta: Titivillus

Digital editor: Titivillus

ePub base r2.1

Notas

[1] Endorsement for the fourth edition, 1978.

[2] This ventriloquistic gift of Berlins left his readers unclear, not for the first time, about where exactly the boundary lay between the exposition of his subjects views and his expression of his own. On 29 October 1939, shortly after the book was published, Berlins friend Mary Fisher wrote to her friend Flora Russell: Did I tell you that last Sunday Corinne & I met Mr & Mrs Berlin pre et mre & Mrs. B. was brought to confess that every weekend Mr. B. reads the book aloud to her & she at intervals interrupts to say Is that Marx or is it Shaya? [familiar form of Isaiah] & he reassures her No no that is only Marx: it is not Shaya?

[3] R. D. Charques, In the name of Marx, The Times Literary Supplement, 7 October 1939, 570. He also wrote: One could wish that Mr Berlin had a taste for shorter sentences, but on the other hand it must be said that his elaborate and almost neo-Augustan precision of style is not without charm.

[4]Political Quarterly 11 no. 1 (January 1940), 127-30 at 128.

[5] Quoted in a letter from Pat Utechin, Berlins secretary, to Henry Hardy, 12 December 1997.

[6] On these cf. (mutatis mutandis) my note on eighteenth-century references in my edition of Berlins The Roots of Romanticism, 2nd ed. (Princeton, 2013), xxv/2.

[7] CW, despite its title, is not complete, but Berlin did not use material by Marx or Engels excluded from it. (Any attempt to distinguish separately published works from articles in journals etc. founders on a broad reef of penumbral cases: so almost all titles of items in CW are given in italics.)

[8] The original contractual allowance was 50,000 words, increased in 1938 in response to Berlins pleas to 65,000 words. Berlin wrote over 100,000 words, which he cut to the published length of 75,000 words. Fisher had told him that squeezing the book into Home University format from its original vaster size, which I pleaded for in 1936 would be the making of the book (IB, letter to Noel Annan, 31 August 1973).

[9] Letter of 28 August 1938, in Isaiah Berlin, Flourishing: Letters 1928-1946, ed. Henry Hardy (London, 2004), 280.

[10] I have dropped the subtitle from the present edition. It doesnt comfortably fit a book so extensively devoted to its subjects ideas, even if environment is understood in an intellectual sense. Life and Opinions, perhaps.

Notas

[1]Moralising Criticism and Critical Morality (1847), CW 6: 318.

[2]Karl Marxs Funeral (1883), CW 24: 467, 468.

[3] Marx to Engels, 15 May 1847, 25 January 1865, CW 38: 117, 42: 66. [Cf. Engels to Marx, 14 January 1848, CW 38: 153, where Engels refers to Hess as the donkey.]

Notas

[1] Letter to Jenny Longuet, 7 December 1881, CW 46: 156.

[2] CW 6: 513.

[3]Address of the Central Authority to the League (March 1850), CW 10: 281.

[4]The Class Struggles in France 1848 to 1850 (1850), CW 10: 127.

[5]My Past and Thoughts (1852-68), part 5, chapter 40 (1850-1; published 1858): op. cit. (70/1), Russian edition x 151-2, English edition ii 775-6.

[6] Jenny Marx to Engels, 27 April 1853, CW 39: 581.

[7] Gustav Mayer, Neue Beitrge zur Biographie von Karl Marx, Archiv fr die Geschichte des Sozialismus und der Arbeiterbewegung 10 (1922), 54-66 at 57-8; quoted here mainly in the translation by B. Nicolaievsky and O. Maenchen-Helfen in their Karl Marx: Man and Fighter (London, 1936), 241-2. [The archival reference given by Mayer is Akten des kgl. Polizeiprsidiums zu Berlin, betreffend die neuerdings bemerkbar werdenden Bestrebungen der Kommunisten 1853 (Pr. Br. Rep. 30. Berlin C. Pol. Prs. Tit. 94, Geheime Prsidial-Registratur Lit . C. Nr 286).]

[8] Marx to Engels, 8 January 1868, CW 42: 517.

[9] Marx to Engels, 22 June 1867, CW 42: 383.

[10] Marx to Engels, 8 September 1852, CW 39: 181.

[11] Marx to Engels, 12 April 1855, CW 39: 533.

[12] Marx to Lassalle, 28 July 1955, CW 39: 544.

[13] In 1851 she bore a son [Marxs, according to some accounts], known as Frederick (Freddy) Demuth, who became a manual worker in London and died there in 1929.

[14] Engels to Friedrich Kppen, 1 September 1848, CW 38: 177.

[15]The Future Results of British Rule in India (1853), CW 12: 217, 221.

[16]The British Rule in India (1853), CW 12: 132.

[17] Engels to Marx, 18 March 1852, CW 39: 67.

[18] Marx to Joseph Weydemeyer, 5 March 1852, CW 39: 62, 65.

[19] Marx to Engels, 7 September 1864, CW 41: 560.

[20] [After the fall of the Second Empire in 1870 Vogts name was found on the list of recipients in 1859 of secret funds. CW 17: xv.]

[21]Speech at the Anniversary of The Peoples Paper (1856), CW 14: 656.

Notas

[1] La rvolution franaise nest que lavant-courire dune autre rvolution bien plus grande, bien plus solennelle, et qui sera la dernire. Manifeste des gaux (1796), in Ph[ilippe] Buonarroti, Histoire de la conspiration pour lgalit dite de Babeuf, suivie du procs auquel elle donna lieu (Paris, 1850), 70-4 at 71.

[2] Marx to Engels, 4 November 1964, CW 42: 18; cf. 20: 15.

[3] CW 20: 14.

[4] CW 20: 12.

[5] CW 20: 13. Cf. 154, 157/2.

[6] Michael Bakunin, Statism and Anarchy, trans. and ed. Marshall S. Shatz (Cambridge, 1990), 135-7.

[7] Letter of 28 October 1869: Pisma M. A. Bakunina k A. I. Gertsenu i N. P. Ogarevu (Geneva, 1896), 233-8 at 234.

Notas

[1] Engels to Wilhelm Liebknecht, 14 March 1883, CW 46: 458.

[2] Preface to the first German edition (1867), CW 35: 10.

[3] Especially if the first volume is taken in conjunction with the posthumously published volumes which Engels, and later Kautsky, prepared for publication out of Marxs economic manuscripts, some in the form of notes.

[4] [For a popular but detailed account of Marxs economic doctrine by David Harvey see Guide to Further Reading, 295.]

[5] Engels to Franz Mehring, 14 July 1893, CW 50: 164.

[6]Capital, vol. 1 (1867), CW 35: 81.

[7] Discours sur les sciences et les arts (1750): Oeuvres compltes , ed. Bernard Gagnebin and others (Paris, 1959-95), iii 6-7.