POLITICAL IDEAS IN THE ROMANTIC AGE

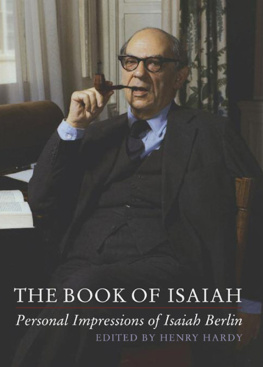

ISAIAH BERLIN WAS BORN IN RIGA, now capital of Latvia, in 1909. When he was six, his family moved to Russia; there in 1917, in Petrograd, he witnessed both Revolutions Social Democratic and Bolshevik. In 1921 he and his parents came to England, and he was educated at St Pauls School, London, and Corpus Christi College, Oxford.

At Oxford he was a Fellow of All Souls, a Fellow of New College, Professor of Social and Political Theory, and founding President of Wolfson College. He also held the Presidency of the British Academy. In addition to Political Ideas in the Romantic Age, his main published works are Karl Marx, Russian Thinkers, Concepts and Categories, Against the Current, Personal Impressions, The Crooked Timber of Humanity, The Sense of Reality, The Proper Study of Mankind, The Roots of Romanticism, The Power of Ideas, Three Critics of the Enlightenment, Freedom and Its Betrayal, Liberty and The Soviet Mind. As an exponent of the history of ideas he was awarded the Erasmus, Lippincott and Agnelli Prizes; he also received the Jerusalem Prize for his lifelong defence of civil liberties. He died in 1997.

Henry Hardy, a Fellow of Wolfson College, Oxford, is one of Isaiah Berlins Literary Trustees. He has edited (or co-edited) many other books by Berlin, including the first three of four volumes of his letters, and is currently working on the remaining volume with Mark Pottle.

Joshua L. Cherniss is a graduate of Yale, holds a doctorate in history from Oxford, and is completing a Ph.D. in political theory at Harvard. He has taught political theory at Yale, Harvard and Smith College, and is the author of A Mind and Its Time: The Development of Isaiah Berlins Political Thought (2013).

William A. Galston is a Senior Fellow and Ezra Zilkha Chair in Governance Studies at the Brookings Institution. His many books on political theory include Liberal Pluralism (2002) and The Practice of Liberal Pluralism (2005).

For further information about Isaiah Berlin visit

ALSO BY ISAIAH BERLIN

*

Karl Marx

The Hedgehog and the Fox

The Age of Enlightenment

Russian Thinkers

Concepts and Categories

Against the Current

Personal Impressions

The Crooked Timber of Humanity

The Sense of Reality

The Proper Study of Mankind

The Roots of Romanticism

The Power of Ideas

Three Critics of the Enlightenment

Freedom and Its Betrayal

Liberty

The Soviet Mind

with Beata Polanowska-Sygulska

Unfinished Dialogue

*

Flourishing: Letters 19281946

Enlightening: Letters 19461960

Building: Letters 19601975

POLITICAL IDEAS IN THE ROMANTIC AGE

THEIR RISE AND INFLUENCE ON MODERN THOUGHT

ISAIAH BERLIN

Edited by Henry Hardy

Introduction by Joshua L. Cherniss

Second Edition

Foreword by William A. Galston

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Published in the United States of America, its Colonies and Dependencies, the Philippine Islands and Canada by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

press.princeton.edu

First published by Chatto & Windus and Princeton University Press

2006

Second edition published by Princeton University Press 2014

The Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust and Henry Hardy 2006, 2014

Editorial matter Henry Hardy 2006, 2014

Introduction Joshua L. Cherniss 2006

Foreword Princeton University Press 2014

The moral right of Isaiah Berlin and Henry Hardy to be identified as the author and editor respectively of this work has been asserted

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-15844-0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

In memory of Solomon Rachmilevich

Born in Riga, 16 August 1891

Naturalised as a British citizen, 5 April 1937

Died in London, 30 November 1953, aged 62

CONTENTS

by William A. Galston |

by Joshua L. Cherniss |

POLITICAL IDEAS IN THE ROMANTIC AGE |

FOREWORD

Ambivalent Fascination

ISAIAH BERLIN AND POLITICAL ROMANTICISM

William A. Galston

A CENTURY AGO, Benedetto Croce published his famous commentary, What Is Living and What Is Dead in the Philosophy of Hegel. Now, more than six decades after the lectures than became Political Ideas in the Romantic Age (PIRA), it is possible indeed necessary to pose a similar question about Berlin.

At the beginning of PIRA, Berlin states that the social and political ideas of leading thinkers of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century are of more than historical interest: they form the basic intellectual capital on which, with few additions, we live to this day.

Not everyone agreed with Berlins assessment. By the early 1950s, some social scientists were propounding versions of what became known as the end of ideology. Despite the continuing presence of Communist parties throughout Western Europe and Fascist-tinged regimes on the Iberian peninsula, many believed that the Second World War and its aftermath had largely settled the great ideological struggles of the interwar period and that the amalgam of democratic institutions, civic and social liberties, and the Welfare State represented the Wests all-but-certain future.

Whatever may have been the case in 1952, it is much harder today to make the case for the continuing ideological relevance of the thinkers Berlin explores in PIRA. To be sure, we have not reached global consensus on liberal democracy an expectation that became fashionable after the collapse of the Soviet bloc. Still, refuted by their consequences, Communism and Fascism have lost not only their grip on the unfortunate nations they once dominated, but also most of their appeal for intellectuals who gravitated to them as alternatives to what they regarded as the shallowness and injustice of bourgeois society. While technocracy is not quite extinct, faith in central planning has surely attenuated. Few now endorse history as the story of progress. Some political theorists still labour to make sense of the General Will, but hardly anyone else cares. Hegels influence on the culture and politics of the West has waned; Nietzsche, the nineteenth-century thinker with the greatest continuing influence, makes only a cameo appearance in PIRA.

As for the people: they may be as shallow and fickle as the nineteenth-century thinkers opposed to liberty and democracy supposed, but the alternatives heroic leaders and vanguard parties such as Russias Bolsheviks proved far worse. The spread of egalitarianism has thrown elitist theories of politics on the defensive. In an ironic victory for the last men, even Nietzsche has been democratised. The few remaining vanguard parties, such as the Chinese and North Korean Communists, rest their case for coercion on political necessity national unity, social tranquillity rather than positive freedom directed by all-knowing authority.

Next page