Contents

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

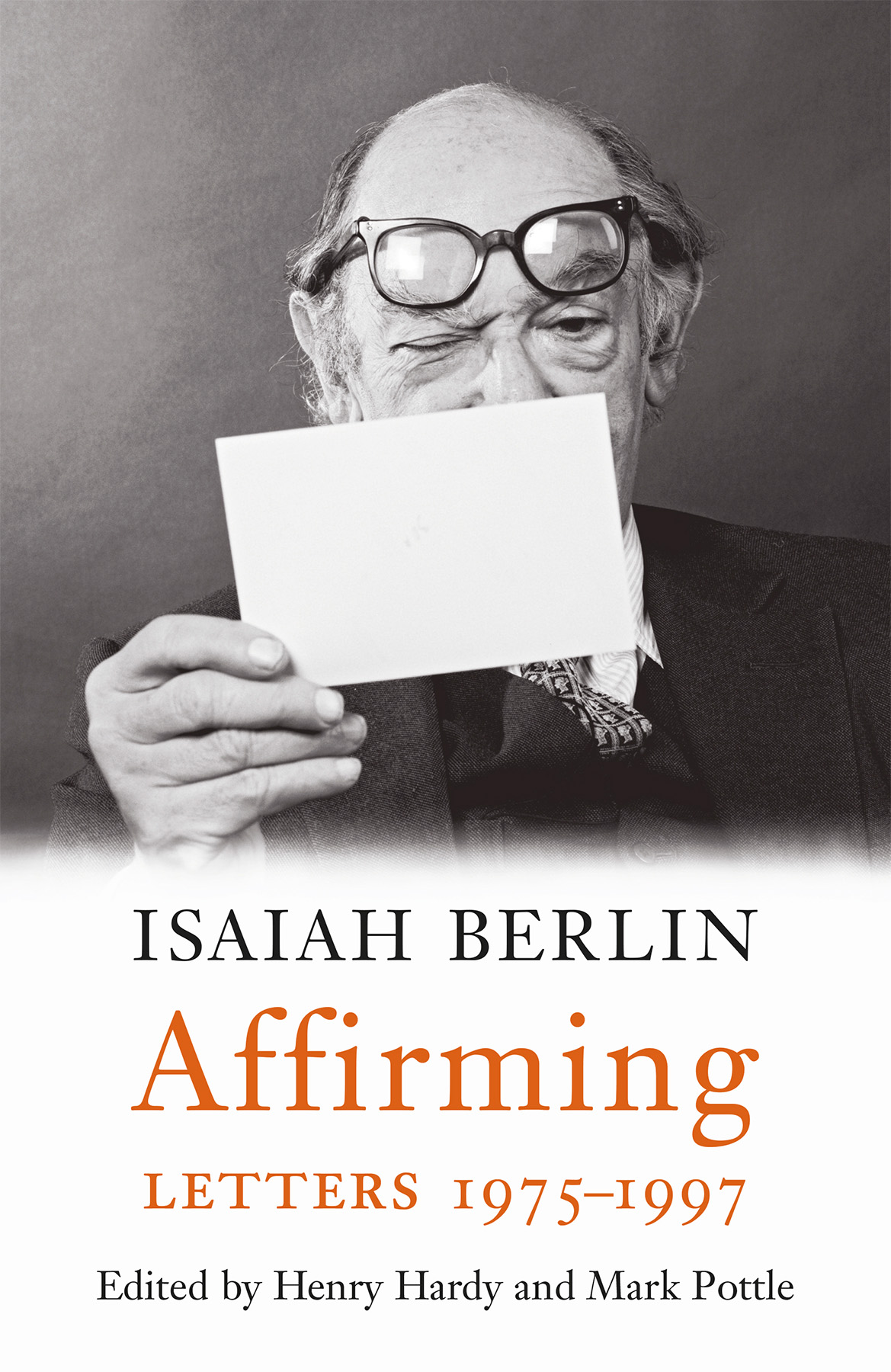

Isaiah Berlin was born in Riga, now capital of Latvia, in 1909. When he was six, his family moved to Russia, and in Petrograd in 1917 Berlin witnessed both Revolutions Social Democratic and Bolshevik. In 1921 he and his parents emigrated to England, where he was educated at St Pauls School, London, and Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Apart from his war service in New York, Washington, Moscow and Leningrad, he remained at Oxford thereafter as a Fellow of All Souls, then of New College, as Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory, and as founding President of Wolfson College. He also held the Presidency of the British Academy. His published work includes Karl Marx, Russian Thinkers, Concepts and Categories, Against the Current, Personal Impressions, The Crooked Timber of Humanity, The Sense of Reality, The Proper Study of Mankind, The Roots of Romanticism, The Power of Ideas, Three Critics of the Enlightenment, Freedom and Its Betrayal, Liberty, The Soviet Mind and Political Ideas in the Romantic Age. As an exponent of the history of ideas he was awarded the Erasmus, Lippincott and Agnelli Prizes; he also received the Jerusalem Prize for his lifelong defence of civil liberties. He died in 1997.

Henry Hardy, a Fellow of Wolfson College, Oxford, is one of Isaiah Berlins Literary Trustees. He has (co-)edited many other books by Berlin including the three other volumes of his letters, Flourishing, Enlightening and Building and by other authors, and is also the editor of The Book of Isaiah: Personal Impressions of Isaiah Berlin (2009).

Mark Pottle is also a Fellow of Wolfson. He has (co-)edited the diaries and letters of Violet Bonham Carter, has collaborated in publishing a number of original First World War documents, and was Research Associate, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2000-2. He co-edited the preceding volume of these letters, Building.

For more information about Isaiah Berlin visit http://berlin.wolf.ox.ac.uk/

ABOUT THE BOOK

The title of this final volume of Isaiah Berlins letters is echoed by John Banvilles verdict in his review of its predecessor, Building: Letters 196075, which saw Berlin publish some of his most important work, and create, in Oxfords Wolfson College, an institutional and architectural legacy. In the period covered by this new volume (197597) he consolidates his intellectual legacy with a series of essay collections. These generate many requests for clarification from his readers, and stimulate him to reaffirm and sometimes refine his ideas, throwing substantive new light on his thought as he grapples with human issues of enduring importance.

Berlins comments on world affairs, especially the continuing conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, and the collapse of Communism, are characteristically acute. This is also the era of the Northern Ireland Troubles, the Iranian revolution, the rise of Solidarity in Poland, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, the fall of the Berlin Wall, Ayatollah Khomeinis fatwa against Salman Rushdie, the spread of Islamic fundamentalism, and wars in the Falkland Islands, the Persian Gulf and the Balkans. Berlin scrutinises the leading politicians of the day, including Reagan, Thatcher and Gorbachev, and draws illuminating sketches of public figures, notably contrasting the personas of Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Andrey Sakharov. He declines a peerage, is awarded the Agnelli Prize for ethics, campaigns against philistine architecture in London and Jerusalem, helps run the National Gallery and Covent Garden, and talks at length to his biographer. He reflects on the ideas for which he is famous especially liberty and pluralism and there is a generous leavening of the conversational brilliance for which he is also renowned, as he corresponds with friends about politics, the academic world, music and musicians, art and artists, and writers and their work, always displaying a Shakespearean fascination with the variety of humankind.

Affirming is the crowning achievement both of Berlins epistolary life and of the widely acclaimed edition of his letters whose first volume appeared in 2004.

Also by Isaiah Berlin

*

Karl Marx

The Hedgehog and the Fox

The Age of Enlightenment

Russian Thinkers

Concepts and Categories

Against the Current

Personal Impressions

The Crooked Timber of Humanity

The Sense of Reality

The Proper Study of Mankind

The First and the Last

The Roots of Romanticism

The Power of Ideas

Three Critics of the Enlightenment

Freedom and Its Betrayal

Liberty

The Soviet Mind

Political Ideas in the Romantic Age

Unfinished Dialogue

(with Beata Polanowska-Sygulska)

*

Flourishing: Letters 19281946

Enlightening: Letters 19461960

Building: Letters 19601975

SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES

The information given here came to our attention too late for it to be included in its proper place.

Cf. A merely well-informed man is the most useless bore on Gods earth: The Aims of Education (the 1916 presidential address to the Mathematical Association of England), in A. N. Whitehead, The Aims of Education and Other Essays (London, 1929), 1.

Machiavelli does not say this explicitly in any of the surviving letters. IB is probably (mis)-remembering that Machiavellis biographer, Pasquale Villari, quite reasonably infers that his letters of 13 and 18 March 1513 to Francesco Vettori, displaying great emotion after his release from a month in prison, where he was tortured, were written with his hands still painful from the rope he had endured: Niccol Machiavelli e i suoi tempi (Florence, 187782) ii 197. The original letters do not survive for us to inspect the handwriting.

We have not traced this particular broadcast, but in an interview with Bryan Magee more than a decade earlier, as part of the Men of Ideas series (65/1), Ayer answered a related question about the defects of logical positivism: Well, I suppose the most important of the defects was that nearly all of it was false. Men of Ideas (67/2), 131.

ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS FROM LARS ROAR LANGSLET

Lars Roar Langslet had first been in touch with IB in 1961 to request permission to publish his work in Norwegian translation. He met IB later that year and asked his advice on a thesis he was planning. Thirty years later, working as a commentator for the Norwegian daily newspaper Aftenposten, he approached IB for an interview, sending his questions in advance, and following these up with a long conversation in IBs London home. His account of the interview was published soon afterwards.

1. I think many would join me in seeing your defence of negative liberty (absence of coercion) as the nucleus of your political thought. Would you agree?

2. It would seem that the negative definition of liberty provides a much more stable and well-defined safeguard of human freedom than the various interpretations of positive liberty, which are sliding towards absolutist forms, undermining or eliminating individual freedom of choice. How would you comment on that?